The dog Laika, the first living being to orbit the Earth, lives on in our memories. Her lethal Sputnik 2 mission, when she was an unwitting pioneer in the USSR’s space program more than 57 years ago, has stuck in our collective consciousness. Her story is central to Lasse Hallström’s 1985 movie, “My Life as a Dog,” and the 2005 Arcade Fire song, “Neighborhood #2 (Laika).” She’s had bands named after her, monuments erected to her, and countless mementos made with her image.

“Working with animals is a source of suffering. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

Laika is not the only canine cosmonaut that died at the hands of the Soviet space program; more than a dozen other dogs lost their lives before her. (Similarly, during the Cold War-fueled Space Race, NASA in the United States sacrificed several monkeys and apes to test flight conditions for humans.) But some Soviet space dogs survived and went on to live relatively normal lives. The next mutts launched into orbit—Belka and Strelka—landed safely, and became beloved pop stars at a time when the USSR frowned on celebrating individual achievements. Laika, Belka, Strelka, and other publicized dog cosmonauts symbolized the ultimate Soviet heroism, seen as simple creatures laying down their lives for their country and the advancement of science. Everything from stamps and postal covers to toys, children’s books, cigarette packages, and candy tins featured these furry icons.

Damon Murray, co-founder of FUEL Design and Publishing in London, came up with the idea to put a book together about the true story of these early space explorers. He collected the images; commissioned Dr. Olesya Turkina, a senior research fellow at the Russian Museum, to write the text; and edited, designed, and published the book with his business partner Stephen Sorrell. The resulting Soviet Space Dogs is a gorgeous work of art, containing adorable image after adorable image of the strays recruited against their will to pave the way for the first man is space, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who orbited the Earth in 1961. Citing Turkina’s text and mining his own expertise, Murray answered our questions about this history via email.

Top: One of many matchbox label designs celebrating the first living being in space. The text reads, “The First Sputnik Passenger—the dog ‘Laika.'” Above: A postcard featuring a photograph taken at the space dogs’ first press conference. The text reads, “Belka and Strelka.” (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: How did Soviet ideology influence the USSR space program?

Damon Murray: Ideologically, socialism could not be seen to fail in any way; it was for this reason that the Soviet space program was kept so secret. It was vital that technological advances were not revealed—both the USSR and the USA attempted to keep any developments they made from each other in what became known as the Space Race.

The flights with dogs were made to determine the effects of space on living organisms. No being had ever experienced such extremes—take-off and landing, zero-gravity. These were all being carefully tested and monitored by Soviet space-program scientists so they could determine whether space-flight was safe for humans.

A 1961 confectionary tin with a portrait of Zvezdochka. The text reads, “Zvezdochka.” (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: Why were dogs chosen over apes or cats?

Murray: Dogs had a history of scientific experimentation in the USSR. Petrovich Pavlov had used them to great effect in his studies of the reflex system. Despite this, apes were initially considered as they more closely resemble man in many ways. Dr. Oleg Gazenko, one of the leading scientists of the space program, even visited the circus to observe the famous monkey handler Capellini, who convinced him that monkeys were, in fact, problematic. They required intense training and numerous vaccines and were emotionally unstable. (Cats did not tolerate flight conditions; that was later proved by French missions in 1963.) The decision was made: Dogs would be the first cosmonauts.

Stray dogs were selected from the streets surrounding the space program’s research center, the Institute of Aviation Medicine, in Moscow. Strays were assumed to be much hardier than purebred dogs, as they had to fend for themselves on the city’s streets. They were selected by weight and dimension: No heavier than 6 kilograms and no taller than 35 centimeters.

A 1959 Soviet matchbox label from the Borisovsky Works shows a space dog flying to the Moon. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: In the beginning, dogs were sent at least 100 kilometers above sea level, but not into orbit. Can you describe these suborbital missions?

Murray: Dezik and Tsygan were the first dogs to be flown in a rocket on July 22, 1951. The scientists were overjoyed at their safe return, running towards the safely landed capsule (even though this was strictly forbidden), shouting “They’re alive! Alive! They’re barking!” Even the head of the space program Sergey Korolev, known as the Chief Designer, allowed himself a moment of celebration—grabbing one of the dogs into his arms and running around in joy. Only a week later Dezik would die alongside another dog, Lisa, when their capsule’s parachute failed to deploy.

The exact number of flights is still unknown, but it is estimated that between July 1951 and November 1960 more than 30 suborbital flights were launched. At least 15 of the dogs involved in these flights died. One lucky dog, Bobik, managed to escape immediately before the mission. He was replaced with another stray who was appropriately named ZIB—these initials stood for Zamena Ischeznuvshevo Bobik, “Replacement for the Disappeared Bobik.”

A 1960 Italian postcard with an image of Kozyavka, wrongly named as Laika on the reverse. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: What became of the dogs after their missions?

Murray: After a successful mission, the dogs were generally used for propaganda purposes. For example, the dog Otvazhnaya (meaning “Brave”) earned her name after her fourth mission. She survived many flights, and became the main hero in the popular children’s book, Tyapa, Borka, and the Rocket, by Marta Baranova and Yevgeny Veltisov. Some dogs were adopted by the scientists who looked after them, as the bond between dogs and human was considerable. For example, after her last mission, the dog Zhulka (formerly “Kometa”) was taken home by the lead scientist Oleg Gazenko. She lived happily in his house for another 12 years. Other dogs spent the rest of their lives at the Institute of Aviation Medicine, like Belka and Strelka, who were the first dogs—indeed, the first living beings—to return safely from orbiting the Earth. They were regarded as celebrities, appearing on television and radio programs of the time.

The dogs were regarded as heroes of the USSR. They were respected for doing their job for the good of country, and also humanity as a whole. Faith in progress and an ability to sacrifice oneself for the common goal became the foundation for personal and communal heroism, forcing the Soviet citizens to work miracles. For the sake of the great goal, it was possible not only to sacrifice oneself, but also other living creatures, who were believed to possess such human qualities as courage and dedication.

Lyudmila Radkevich, associate researcher at the Institute for Aviation and Space Medicine, checks Chernushka’s weight in the laboratory in 1958. (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: How did the scientists and engineers feel about the dogs they worked with?

Murray: There are many accounts of how devoted the scientists became to their charges. Even the Chief Designer, Korolev, when he once found the dogs’ bowls empty, sent a guard to the stockade. Before her flight, the same Chief Designer whispered into the ear of the cosmonaut Lisichka (meaning “Foxy”): “It is my deepest desire that you come back safely.” Lisichka died. Because of the secrecy surrounding the program, it was unthinkable that the four-legged heroes who perished in these experiments might receive a stately burial. So the scientists were unable to mourn. But there were exceptions. In 1955, after the death of his favorite dog, Lisa 2 (meaning “Fox”), Aleksander Dmitriyevich Seryapin, an employee at the Institute of Aviation Medicine, defied regulations and buried her remains on the steppe, even bringing a camera to surreptitiously photograph the spot as a memento.

Commenting on the death of Laika in Sputnik 2, one of the leading scientists, Oleg Gazenko stated that: “Working with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

The text (in French and Dutch) on the reverse of this 1964 Jacques chocolate card, “Assault on the Stars,” explains how dog astronauts helped man explore the physical effects of space flight. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: How did the dogs eat and relieve themselves onboard?

Murray: The problem of feeding the dogs in zero-gravity was solved by bonding nutrients with agar, a jelly-like substance. This “jelly” could then be easily consumed, minimizing waste. The most tricky obstacle for the dogs traveling into space was to find a way for them to relieve themselves in such unusual conditions. Although their suits had special receptacles for urine and feces, it was difficult to train the dogs to use them. They prefer to relieve themselves outdoors, never inside a room or a cockpit, and certainly not inside clothes. This process was unnatural for the dogs, only those who took to it more easily were selected. For orbital flights, all the dogs were exclusively female: As there was no room in the cabin to cock their legs, they were better suited to space.

The packaging of a Laika clockwork toy made by the GNK company in West Germany between 1958 and 1965. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: When and why did the USSR start publicizing the space dog experiments?

Murray: Kozyavka, Linda, and Malyshka were the first dogs’ names to be declassified, and were announced to the public in June 1957. They had flown to the very edge of space 110 kilometers above the Earth. The next step for the Soviet space program would be the first orbital flight by a living being: Laika.

The Soviet publicity machine used every opportunity to demonstrate that post-flight these dogs were still able to give birth to healthy puppies. This was proof they suffered no ill effects from their adventures—which was vital if the next step was to put a man into space. One of Strelka’s puppies, named Pushkina, was even given as a present to President John F. Kennedy’s daughter by General Secretary Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev. Fearing the Russians had found a way of secreting a bugging device on or in the puppy, she was thoroughly examined and scanned internally by the Secret Service, before being passed on to the president’s family.

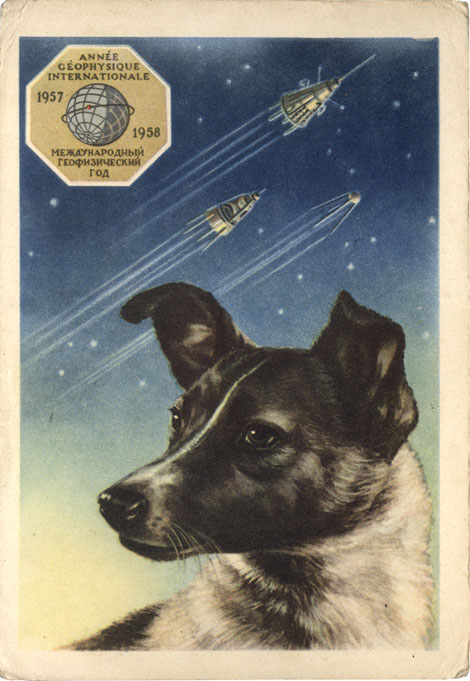

A portrait of Laika by the artist E. Gundobin, with the first three Sputniks in the background. Text of this 1958 postcard from the USSR reads “International Geophysical Year 1957–1958.” (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: How did Laika get selected to be the first dog in orbit?

Murray: Laika was chosen because during pre-flight training, she had demonstrated an exceptional capacity for endurance and tolerance. These were the admirable characteristics that would condemn her to a martyr-like death for the benefit of the human race. In addition, she was a striking dog, light in color but with dark brown spots on her face, which possessed a surprised expression. Crucially, her image reproduced well in black-and-white photographs and film footage. This was an important factor, as it was recognized that the launch would be historically significant and, therefore, would be meticulously recorded.

Collectors Weekly: Why did they launch Laika before they knew how to recover her?

Murray: The ideology of the Space Race meant that there was no time to develop a recovery system before sending Laika into space. Following the sensational launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957, Khrushchev had told the scientists that another space satellite needed to be launched in honor of the rapidly approaching 40th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution on November 7, 1957. This meant that Sputnik 2 had been prepared in a frantic rush.

Made by S. I. Toys, this 1958 spinning top depicts Laika standing on a version of Sputnik 2 surrounded by a space-themed frieze. Initially, the lack of images released by the Soviet space program meant it was assumed that Sputnik 2 had the same design as Sputnik 1. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: What was the world’s reaction to Laika’s launch and death?

Murray: Laika’s flight had inspired unprecedented affection and compassion, both in the USSR and in the rest of the world. The West felt genuine compassion for Laika. She was perceived as an innocent victim, caught up in the brutal Cold War drive to be first at any cost. To Soviet children, the story of Laika was a heroic fairy tale about a kind and intelligent dog that had flown away into space. To adults, her fate ostensibly resembled their own. It was no accident that on the bas-relief of “The Monument to the Conquerors of Space,” erected in Moscow in 1964, the image of Laika (or a similar little dog bearing an uncanny resemblance) appeared alongside images of nameless engineers and scientists whose identities could not be revealed. This 350-foot silver obelisk in the shape of an exhaust plume is crowned by a rocket ascending into the sky. It came to symbolize the hopes and dreams of an entire generation of Soviet people.

A Chinese matchbox label depicts Laika in a Sputnik-style spacecraft. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: What did the Soviet publicity machine say about her death at the time, and when did the truth come out?

Murray: After the initial excitement that followed the launch of Sputnik 2, they now had to explain to the rest of the world why Laika would never return. During the seven days that she was officially “alive,” newspapers would periodically publish reports on her health. After this period, an announcement was made that stated she had lived in orbit for a week, during which time she had served as a source of priceless data on the plausibility of life in space; then, she had been painlessly euthanized. There were several accounts of how she had died. First, a euthanasia drug was remotely injected. Second, a euthanasia drug was administered with food. Third, by the eighth day, she ran out of oxygen.

In reality, due to a thermal conductivity miscalculation, Laika had suffocated just a few hours after the launch; this fact was only revealed in 2002. In the 1950s, the international press accused the Soviet totalitarian regime of inhumanity and suggested that General Secretary Khrushchev should have been sent into orbit instead. In response, the Soviet press wrote about the hypocrisy of capitalist morality, the exploitation of entire nations in the colonies, and racism. Regardless of these arguments, Soviet ideology was faced with a serious dilemma. Since denying Laika’s death was impossible, their only viable option was to immortalize her.

The cover of the popular 1961 Russian children’s book, “The Adventures of Belka and Strelka” by Yuri Galperin. (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: When Belka and Strelka were launched into orbit, what developments had been made since Laika’s launch?

Murray: Their capsule had been fitted with a camera that transmitted live images from space to Earth in real time. Following Belka and Strelka’s landing, a documentary about the preparation for their flight—which included that first live space broadcast—aired on television. The whole nation watched Strelka merrily spinning in zero-gravity, while Belka, on the contrary, remained reserved and watchful.

The children’s story, The Adventures of Belka and Strelka, describes accurately how they trained to wear their snug-fitting suits, which are attached to various wires. They courageously endure cold and heat in the training capsule, and are confined for several days at a time in a cramped re-entry module, where they are unable to walk, only sit or lie down. Inside, they learn how to eat gelatinous food delivered by an automatic dispenser. They are spun on a merry-go-round and trained to tolerate rocket noise by listening to recordings. They are tested on a vibrating table and have to sleep in a brightly lit kennel. They are even flown in an airplane. But the most severe trial for the dogs is the ejector seat, in which they are suddenly shot up into the air, descending slowly down by means of a parachute.

Originally, the team of Chaika and Lisichka were intended to make this mission. However, they died tragically on July 28, 1960, when their rocket exploded on the launch pad. They had been the favorite dogs at the institute. Associate researcher Lyudmila Radkevich later recalled how bright and lovable they were, in particular Lisichka. It was later suggested that sending a red-haired dog into space was a bad omen.

One of the sweet tins that were given to young guests of the New Year’s Eve party celebrating 1960 at the Kremlin. (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: Can you describe the flight of Belka and Strelka?

Murray: The launch of the rocket containing Belka and Strelka took place on August 19, 1960, at 15:44:06. Alongside Belka and Strelka, the space mission included an ejecting container with twelve mice, insects, plants, fungi cultures, various germs, sprouts of wheat, peas, onions, and kernels of corn. In addition, the cabin contained twenty-eight lab mice and two white rats.

“The scientists were overjoyed at the space dogs’ safe return, running towards the capsule—even though this was strictly forbidden—shouting ‘They’re alive! Alive! They’re barking!'”

Only after the first orbit did the dogs begin to bark. Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky, the lead scientist of biological research in the upper layers of the atmosphere and outer space, declared that as long as the dogs were barking, and not howling, they were sure to return to Earth. A huge step forward was the televisual transmission from the spacecraft, which allowed the scientists to closely monitor the dogs in flight for the first time. They became so quiet at the launch, that were it not for data from sensors attached to their bodies, it would have been difficult to ascertain whether they were still alive.

As expected, owing to the g-forces of blast-off, their heart rates and breathing had speeded up, but they quickly returned to normal. However, on the fourth orbit, Belka began to wriggle out of her harness, barking and vomiting. This reaction played a key role in the subsequent decision to send the first human cosmonaut into space for the shortest period possible: a single orbit. Belka and Strelka remained in flight for more than 24 hours, allowing the scientists enough time to study the prolonged influence of zero-gravity and radiation on live organisms. During the 18th orbit, on August 20, at 13:22:00, the order was given to decelerate, and a short time later the re-entry capsule containing the dogs landed safely on the ground.

Soviet space researcher Oleg Gazenko holds Strelka (left) and Belka (right) aloft at the 1960 press conference immediately after their landing. In his memoirs, Gazenko referred to this as the proudest moment of his life. (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: What was the reaction to Belka & Strelka’s return?

Murray: Following their triumphant landing, they appeared on radio and television, and their portraits were featured in newspapers and magazines. They were chauffeured to celebratory meetings with selected Soviet citizens. Politicians, outstanding laborers, schoolchildren, and celebrities—both Soviet and international—considered it an honor to be photographed with this famous pair. Portraits of the two dogs, adorably dressed respectively in red and green spacesuits, appeared in every conceivable place: on chocolates, matchboxes, postcards, lapel badges, postage stamps, and toys.

Collectors Weekly: Why were the capsules outfitted with self-destruct mechanisms?

Murray: The importance of the advanced technology of the spacecraft meant that it was vital they did not fall into the hands of the USSR’s competitors in the space race: the USA. During the orbital space flight of a mission on December 1, 1960, the trajectory of the re-entry module deviated from the programmed course. When the system registered the risk of landing outside USSR territory, the on-board self-destruct mechanism was activated. The dogs Mushka and Pchyolka, who had orbited the Earth 17 times, were killed in this way.

A 1960 USSR space propaganda poster by the artist K. Ivanov, featuring Strelka and Belka. The text reads, “The way is open to man!” (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me about the “cosmonaut” Ivan Ivanovich?

Murray: Ivan Ivanovich was a mannequin. He was flown as an immediate forerunner to Yuri Gagarin to gain a more accurate idea of the pressures of spaceflight on man. He was dressed in the same orange spacesuit that would later be worn by the first cosmonaut. Inside his chest cavity, abdomen, and hip area were housed the entire spectrum of Darwinian evolution. This “Noah’s ark,” as it was later christened by foreign journalists, contained mice, guinea pigs, and various microorganisms. The effects of spaceflight were being tested on all these creatures.

This 1961 Bulgarian stamp shows a group portrait of Strelka, Chernushka, Zvezdochka, and Belka, taken at the press conference held on March 28, 1961. (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: Were any dogs sent up after the first cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, and why?

Murray: Yes. As technology improved, it became possible to increase the duration of manned missions, and so it was necessary to investigate how humans might be affected by long-term space flight. Consequently, on February 22, 1966, a man-made satellite was sent into orbit carrying two dogs on board: Veterok (meaning “Little Wind”) and Ugolyok (“Little Piece of Coal”). The dogs did not fare well on the long flight. In fact, they were taken out of orbit sooner than planned. After landing, Veterok and Ugolyok suffered from dehydration and bedsores. However, they were quickly rehabilitated and, later, birthed healthy puppies. Their flight lasted 22 days, which is still the record for a dog in orbit. At that time, it was also the record for any living being in space and would remain so for another five years, until finally broken by Soviet cosmonauts on the ill-fated Soyuz 11 mission.

A 1960 USSR postcard showing Belka and Strelka in their rocket by the photomontage artist Sveshnikov. The flags read, “Happy New Year,” the wing of the rocket reads, “‘USSR,” and inside the cockpits, it says, “Strelka” and “Belka.” (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: How were the dogs and their achievements memorialized?

Murray: The idea of building memorials to the space dogs already had emerged during the period when they were being sent into space. However, because the USSR was so oriented toward the future, the main symbol of which was the continuing space program, this ambition remained unrealized. Once man had successfully entered space, the attention was focused on human rather than canine cosmonauts.

“The space dogs were regarded as heroes of the USSR. For the sake of the great goal, it was possible not only to sacrifice oneself, but also other creatures, believed to possess such human qualities as courage.”

The first memorial to Laika was actually built in Paris in 1958. A granite column was erected in front of the Paris Society for the Protection of Dogs, to commemorate the animals who had given their lives in the name of science. The dedication reads: “For the first living being to reach outer space.” Crowning the column is a figure of Laika peering out of Sputnik 1. In Japan, Laika’s image became the symbol for the Year of the Dog in 1958, which led to the manufacture of great quantities of Laika souvenirs.

The Finnish rock group Laika and the Cosmonauts was formed in 1990, followed by the emergence of a British band Laika in 1993. Only in 2008, for the 50th anniversary of Laika’s flight into space, was a monument erected to her in Moscow. Located in the courtyard of the Institute of Aviation Medicine, it was constructed following a petition by scientists to preserve the memory of the four-legged cosmonaut. Artistically, this monument can hardly be called a success, although those who knew Laika say that the life-sized sculpture bears a strong resemblance. The small dog, its face lifted skywards, is standing on top of a rocket in the shape of a giant open hand. Importantly, it recognizes that the dog was a sacrifice made for and by humans.

A 1962 Magadan philately club envelope, marking the fifth anniversary of Sputnik 2. The stamped text reads, “Price stamped 13 kopecks. Registered by air. 5 years since the date of the flight. Magadan.” (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

Collectors Weekly: How did space dogs influence the Soviets’ opinions of mutts and strays?

Murray: After Belka and Strelka’s flight, Soviet schools initiated lessons on how to be kind to stray dogs on the street, and the price of mixed-breed puppies at the Bird Market, the main pet market in Moscow, doubled, since any mongrel, if it wasn’t too large, could become a cosmonaut. Even after Laika’s tragic flight, Soviet citizens wrote letters to the government volunteering themselves to be sent into space. Requests for permission to fly into orbit increased immeasurably following the successful landing of Belka and Strelka. Only yesterday, the space dogs had been so close, roaming the courtyards of Moscow, and yet today, their heroic missions complete, so distant. They became an ideal, and this ideal was perfectly human: To sacrifice yourself for the sake of humanity at large, and if you were lucky, become a hero, beloved by the whole country.

A 1972 Soviet postcard depicting Belka and Strelka in the “cockpit” of their rocket, by the artist L. Aristov, from the collection titled “Friends of Man.” (© FUEL Publishing)

Collectors Weekly: What was the Bion program and what did it symbolize between the US and USSR?

Murray: The Bion program, in contrast to the dog program, was not only concerned with the possibility of sending animals into space, but also with the complexities of sustaining living beings in orbit for extended periods of time. It began in the USSR in 1973, and in 1975, American scientists were invited to participate. The Bion project played a special role in dissipating the Cold War ideological opposition between the forces of “Good and Evil,” which had been the basis of propaganda in both the USA and the USSR.

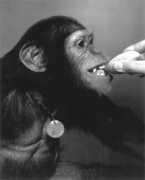

Collectors Weekly: Why were monkeys chosen for Bion instead of dogs?

Murray: Monkeys were chosen for the Bion program as their physical make-up is so similar to that of a human. All the monkey pilots would have their tails removed so they could fit into their capsules. They would also have electrodes implanted in their brains. In his memoirs, Oleg Gazenko, the scientist who prepared the monkeys for their flights, professed that it was impossible not to feel pity for the outstretched monkeys, lying on the surgical table with wires protruding from the shaved crowns of their heads.

A 1991 phone card showing two of the Soviet space monkeys who followed the dogs into space. The text reads, “1980s… The monkeys Dryoma and Erosha return from space.” (© FUEL Publishing / Marianne Van den Lemmer)

The monkeys did not fare well. The last crew spent 15 days in space, from December 24, 1996, until January 7, 1997. This flight of Multik and Lapik was sponsored by the Americans. By that time the Soviet Union had ceased to exist, so there was no funding for the space program. After landing, Multik died in surgery, following an adverse reaction to anesthetic. Multik’s death was the end of the monkey space program. The USA refused to participate further, even though another satellite launch with two apes had already been planned. The experiments were stopped as a result of both the influence of public opinion and the lack of resources. In 2010, the monkey Krosh, a space veteran, died at the age of 25. He and his comrade, Ivasha, were sent into space for 12 days at the end of 1992. He spent his final years with his offspring at the Adler Institute, where he lived as an honorary retiree—the last monkey-cosmonaut in Russia.

Collectors Weekly: How does Russian public opinion influence new ideas about sending monkeys or apes to Mars?

Murray: Public opinion has had a great influence over the future of animals in space. In 2008, the Russian Space Agency announced that a monkey from the Sukhumi centre could become the first creature sent to Mars. This provoked protests from the European Space Agency and animal protection organizations. Similar protests took place when it was suggested that monkeys might be exposed to long-term radiation within the Mars 500 program. The Russian Federation has now abandoned the idea of sending higher mammals into space, especially dogs and monkeys.

The cover for “Soviet Space Dogs,” with text by Olesya Turkina, edited by Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell. (© FUEL Publishing)

(To read more about these animals, check out FUEL Publishing’s “Soviet Space Dogs” by Olesya Turkina, edited by Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art

Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art

Tag Worn By U.S. Astrochimp Up for Auction

Tag Worn By U.S. Astrochimp Up for Auction Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art

Circling the Globe With the Mid-20th Century's Most Brilliant Matchbox Art Cartoon Kittens and Big-Eyed Puppies: How We Bought Into Processed Pet Food

Cartoon Kittens and Big-Eyed Puppies: How We Bought Into Processed Pet Food Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa…

Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa… DogsIs there an animal more closely linked with humankind than the dog? Our his…

DogsIs there an animal more closely linked with humankind than the dog? Our his… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

As a person who is fond of dogs (having grew up with them), I was really fascinated by this article. I though it was only “Laika” and “Belka & Strelka” who were sent into space; I had no idea that other dogs, and indeed, other animals, were sent into space also. I really enjoyed reading this article and will certainly recommend it.

Sickened by all the nonsense about the scientists doing on the poor unfortunate animals. How could they participate in such horrendous cruelty ?

My question is: Did Laika have an impact on Belka and Strelka’s ability to travel to space and back safely? Did scientists use Laika’s experience and data collected on her in order to safely send dogs into space?

Answer to Sasha : of course the flight of Laika had a huge impact on what the scientist learned. The chief-engineer Sergei Korolev studied for 3 more years before he sent new dogs to space. He was then able to let them return safely.

Answer to Sarah : Hundreds of poor small stray dogs were taken from the streets of Moscow. Some were able to help in the space program, many were not (too scared, to aggressive etc).

But they were ALL adopted afterwards, the dogs were well taken care off.

If you read the book, you will learn how much the space dogs were respected, loved and considered ‘comrads’.