When “Love Is a Drag” hit record-store shelves in 1962, it was decidedly not a sensation. Only a few shops carried the album, which featured jazz standards performed by an anonymous singer and band, and its label flopped shortly after the release. But beneath this mundane veneer, the record’s content was remarkably provocative, becoming the first major release to feature a male singer crooning love songs about other men.

“It was subtle, under the table almost.”

Like a magic mirror held up to America’s heteronormative postwar culture, its music reflected a dignified, and seductive, vision of gay life. Just below the album’s title read the teaser: “For adult listeners only—sultry stylings by a most unusual vocalist.” For those LGBTQ folks in the know, this record offered a glimpse of the acceptance they’d long been denied, subtly placing gay romance into the standard musical canon. And yet, at a time when even urban LGBTQ communities were mostly invisible, “Love Is a Drag” lacked the publicity needed to really make waves.

For 50 years after its initial release, the album languished, failing to make any headway beyond the close-knit queer scenes in major cities like Los Angeles and New York. But a few years ago, after Houston-based audiophile and archivist J.D. Doyle began playing tracks from the mysterious album on his radio show, he received an email that changed everything.

By 2012, Doyle had built an extensive online archive of LGTBQ music history as part of his monthly radio show, Queer Music Heritage, and amassed the country’s top collection of queer music and related ephemera. Yet he still had no idea how “Love Is a Drag” had been made so far ahead of its time. “Around the mid-’90s, I started focusing on gay and lesbian music, so that was probably when I first discovered this album,” Doyle explains. “It was definitely something that would have caught my eye.”

The front cover of “Love Is a Drag” (top) and the album’s backside (above) were photographed and designed by the Garrett-Howard studio in 1962. Images courtesy of J.D. Doyle.

“The back of the original album doesn’t say who it was produced by,” he continues. “It doesn’t give the singer’s name or the producer’s name. All it says is ‘Cover Photo and Back Liner Design: Garrett-Howard, Inc.’ I thought that was just the photographer; I didn’t know that was the photographer and producer.” After Doyle launched his radio show in 2000, he made sure to carefully document each episode on his website. “If you just play a song on the radio, it’s gone. There’s no trail,” Doyle says. “So my approach was that everything should be archived online to create a permanent resource, and that’s how Murray Garrett found me.”

Garrett had been a lifelong photographer for the entertainment industry in L.A., and his company had been instrumental in producing the secret gay album. “When he sent me that email, it felt like finding a holy grail,” Doyle says. “I was stunned, and immediately asked him for an interview. I was just over the moon.” At 85, Garrett finally wanted to reveal the unlikely origin story behind “Love Is a Drag,” and credit the artists who made the subversive recording possible.

Beginning in the 1950s, Garrett and his friend Gene Howard, a vocalist-turned-portrait-photographer, co-owned a photographic and design studio in Los Angeles called Garrett-Howard, Inc., whose subjects included celebrities like Bob Hope, Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant, Natalie Wood, Marilyn Monroe, and Frank Sinatra. Though Garrett and Howard were both straight and married to women, the idea for “Love Is a Drag” had come from one of Garrett’s fond memories of gay Greenwich Village.

“Back in 1946, shortly before he moved to L.A., Murray was living in New York City. He was in a club with some friends and wasn’t really paying attention to the fact that it was a gay club, but suddenly Murray realized the male performer was singing standards with male pronouns like ‘The Man I Love’ or ‘Can’t Help Lovin’ That Man of Mine,’ and he was really taken by that.”

As New York City’s bohemian center, Greenwich Village hosted several popular gay bars and jazz clubs in the 1940s. Here, singer Doc Pomus jams at the Pied Piper in 1947. Photo by William P. Gottlieb, via the Library of Congress.

In Doyle’s 2012 interview with Garrett, the photographer discussed his surprise that night in New York. “I’m sitting there listening to this guy sing,” Garrett explained, “and I’d be damned if he’s not singing what I would have called the ‘girl lyrics.’ … I was really square. I had no idea what was happening, and one of the people with me, when I mentioned that, said, ‘Well, don’t you understand what’s going on?’ I said, ‘No, what’s going on?’ And he explained that the guy was gay, that we were in an essentially gay nightclub that catered to good musicians.”

The act was so untraditional that Garrett couldn’t get it out of his head. “Somehow or another that stayed in my mind for years and years, and every time I’d hear one of these songs, I’d smile,” Garrett said.

Flash forward to the early ’60s, when Garrett’s friend Jack Ames was running a new record label called Edison International. Ames approached Garrett about doing graphics for Edison releases, and asked if he had any unusual album ideas for his label. “Murray told him about his experience listening to this cabaret singer in the 1940s, a memory that had stuck in his mind all that time,” Doyle says.

Ames was taken with the idea, but didn’t want one of the first releases on the Edison label to pigeonhole the company’s future work, so he decided to produce it anonymously using a different label name—the campy-romantic “Lace Records.” Despite the cloak-and-dagger routine, all involved parties agreed the album would be made respectfully and with the best possible musicians; they weren’t going for a novelty angle. But they still had to find a singer, and Garrett thought he knew just the guy.

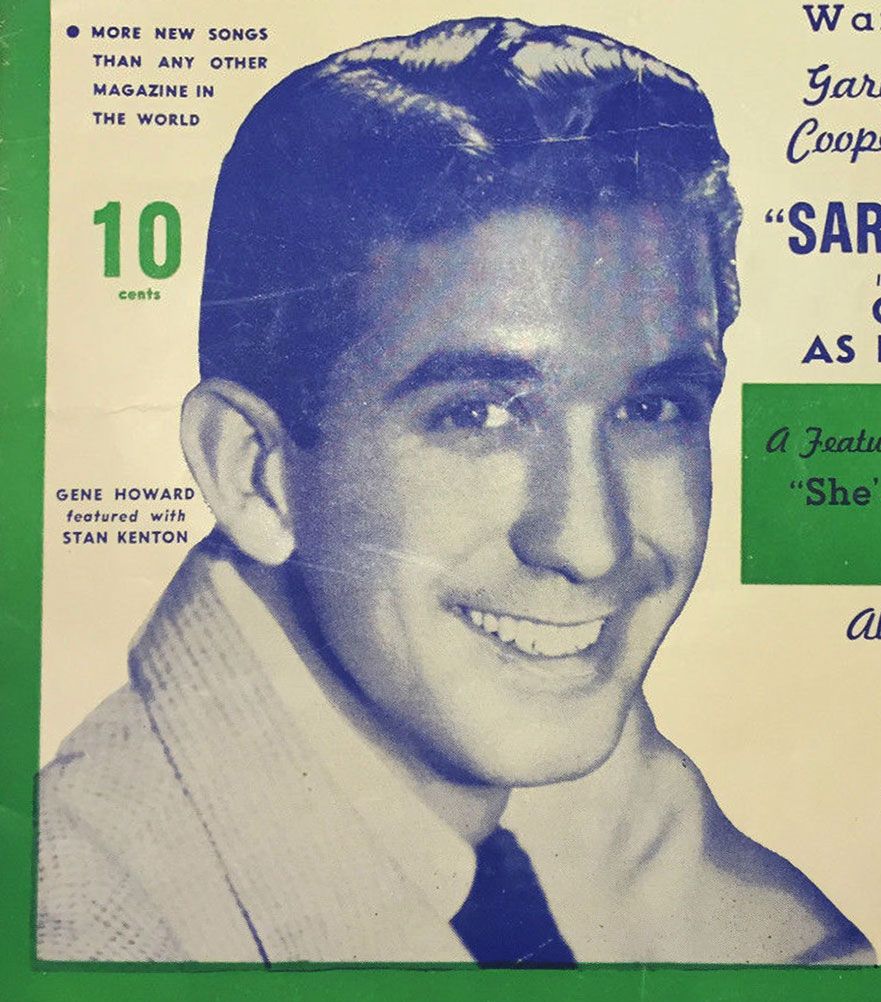

Vocalist Gene Howard as seen on the cover of “Best Songs” magazine from 1945, during the height of his Big Band fame.

“When Murray asked Gene Howard about recording the vocals for the album, he said, ‘Oh, I don’t know, my wife would have a fit,’” Doyle says. Howard’s wife eventually approved, but insisted that the recording had to be done with dignity, and she wanted to be in the studio when it was made. To back Howard’s vocals, Ames’ team at Edison put together a group of established studio musicians for the various instrumentals: Dick Shanahan on drums, Heinie Beau on flute, Bobby Hammack on piano, Morty Corb on bass guitar, and Al Viola on guitar.

Garrett supposedly also came up with the record’s title, “Love Is a Drag,” whose meaning is explained in fine print on the back of the album as “Drag: (in music vernacular, a bore, a headache).” It’s unclear if he ever acknowledged the more coded definition of the word “drag,” long used in the queer community to describe someone flamboyantly dressed as the opposite gender.

The album’s limited pressing was finished in 1962, making it the first complete album of gay subject matter in American music history. Despite its groundbreaking substance, the record received zero media coverage, partly because the producers agreed to keep all the musicians anonymous. “The mystery was supposed to sell the album in the first place,” Doyle explains. “Famous people like Frank Sinatra were trying to guess who the vocalist was, wondering, ‘Do I know this person?’ If they had credited Gene Howard originally, it would’ve been totally different.

“Part of their marketing angle was that they wanted the music to stand alone—they didn’t want to focus on the singer,” Doyle continues. “For one thing, the singer wasn’t gay.” In fact, no one connected with the album’s production was gay, including the two Garrett-Howard studio employees who modeled for the cover.

Love Is a Drag, sides one and two. Image courtesy J.D. Doyle. (click to enlarge)

Because there was no mainstream gay audience, the producers had no idea how to reach gay listeners. “Some copies went to the biggest record store in L.A., which happened to be across the street from a restaurant that almost exclusively employed gay waiters,” Doyle says. “The store’s owner contacted Murray and said, ‘Hey, this thing is selling like hotcakes. These waiters are buying half a dozen copies at a time and telling all their friends.’ So the producers realized they should market it in gay neighborhoods and sent some copies to San Francisco and New York, but that was about the limit of what they could think of then.”

“I’m sitting there listening to this guy sing, and I’d be damned if he’s not singing the ‘girl lyrics.’”

As if to ward off potential criticism that “Love Is a Drag” was indeed for queer audiences, the jacket also included a bizarrely misogynist justification for men to sing standards with male-centric lyrics: “Were they not written by men? And haven’t they been played by the best men musicians of our time? Think what would happen if orchestrations of these great songs could be performed only by girl musicians!” The text continues to argue that the album’s singer was courageous and “is to be congratulated,” despite the fact that it never reveals who this mystery man actually is.

Beyond the word-of-mouth in the gay community, several copies of “Love Is a Drag” also made it into the personal collections of Garrett-Howard’s celebrity clients like Frank Sinatra and Bob Hope. “The Liberace story; that’s my favorite,” Doyle says. “The album had not even been released yet, although it was manufactured and had a finished cover. Murray’s studio had an appointment to shoot the photograph for Liberace’s next album, ‘Rhapsody by Candlelight.’” Liberace came to the studio for the photo shoot, bearing his own candelabra, and while he was changing into his stage outfit, Garrett put “Love Is a Drag” on the studio’s record player. When Howard realized what was happening and started to object, Garrett kept him quiet, letting the record play during throughout their photo session.

Garrett played the freshly recorded “Love Is a Drag” in his studio while shooting the 1962 cover image for Liberace’s “Rhapsody by Candlelight.”

As Garrett explained to Doyle in 2012, “When the shoot was over, [Liberace] went back into the dressing room, got out of his costume, back into his street clothes, picked up his candelabra, and very quietly walked over to the turntable, picked up the record, and said, ‘Ta-ta.’ And he walked out with the record,” Garrett remembered.

“He didn’t ask for it; he just took it,” Doyle says, laughing. “Liberace later told Murray several times that they had produced his favorite album.” Based on the Liberace album cover, Doyle was able to definitively date “Love Is a Drag” to 1962.

Despite these famous fans, the Edison label was mismanaged by Ames and began to fail before it could invest in marketing the album. “Murray had thought that after it was sold for a while, they’d have a big promotion and release the names of the artists,” Doyle says. “But it never happened because ‘Love Is a Drag’ didn’t sell well, so it just stayed a secret.”

Vocalist Gene Howard died in 1993, long before his role in the album had been publicly revealed, so he never received any accolades for the pioneering gay album. However, Garrett made it clear that the men had created an album they were proud of, one they were comfortable sharing with their gay friends. “As I look back at my lifetime, ‘Love Is a Drag’ was one of the highlights of my life,” he told Doyle.

Around 2000, the record-reissue label Sundazed purchased the entire Jack Ames catalog, including “Love Is a Drag” and his other work for Edison International. While researching Ames, creative director Jay Millar discovered Doyle’s interview with Garrett and hunted down a personal copy of the LP. “I had no idea that that was part of the purchase until some time later when I brought it up to Bob, the owner of Sundazed and Modern Harmonic,” Millar explained via email. “He pulled it from the tape vault and texted me a photo of the tape box, and I about fainted.” In November 2016, Sundazed re-released “Love Is a Drag” through its subsidiary, Modern Harmonic, on both CD and gold vinyl LP with new liner notes from Doyle accompanying the album’s original text.

Though the story behind “Love Is a Drag” adds a remarkable early chapter to queer music history, it isn’t the last musical conundrum Doyle has faced. Only a few years after “Love Is a Drag” was originally released, another mysterious label called Camp Records put out a series of gay albums whose artists remain unknown today.

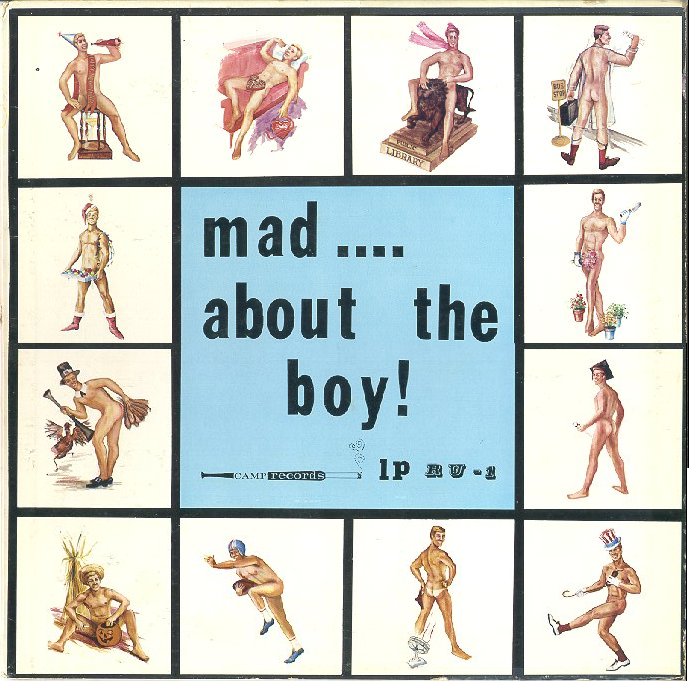

The cover for Camp Records’ “Mad About the Boy” used pinup imagery in an homage to Julie London’s 1956 album “Calendar Girl.” Courtesy J.D. Doyle.

Unlike Edison, Camp Records released several comical singles with over-the-top gay innuendo. “They released one album of 10 tracks, plus singles for each of those tracks, and then a second LP that was stylistically very different,” Doyle says. “The first LP was very stereotypically gay—some people might even be insulted by the music because the voice inflections and lyrics are so campy. But back then, gay people had so few gay contacts or communities, and this was at least something.” The second album was more similar to ‘Love Is a Drag,’ featuring an unidentified male vocalist singing standards with male pronouns.

“I found the records first, and then located ads for them in some of the mail-order catalogs from the mid-’60s,” Doyle explains. “The earliest ad for Camp Records I’ve found was in a 1964 issue of Vagabond, a catalog published by one of the major companies distributing physique magazines, advertising things like books, cologne, greeting cards, photos, what the so-called ‘gay market’ was then. I found ads for Camp Records in several publications for a short period of time around 1964 and ’65.”

At that time, since gay pornography was illegal under obscenity laws, gay men circulated so-called “physique magazines,” which featured muscular men photographed in provocative situations, although never fully nude. “They marketed Camp Records to that audience, but it wasn’t an explicit gay market,” Doyle says. “It was subtle, under the table almost.”

But beyond these advertisements, Doyle has never located any business entity or people associated with the Camp Records releases. “It’s like they didn’t want anybody to know who was behind the label,” Doyle says. “You can’t track any producers or musicians. There’s a company listed, Different Music Co., but who knows if that was the real name, since I couldn’t find any information about it.”

Ads for Camp Records’ singles as seen in Vagabond No. 7, 1965. Silly song titles included “Homer the Happy Little Homo,” “Mixed Nuts,” and “Leather Jacket Lovers.” Courtesy of J.D. Doyle. (click to enlarge)

Though Camp Records created several albums aimed at gay audiences, Doyle doesn’t think these limited releases really opened the door for queer music. “If you asked me when music was first geared to the gay and lesbian market, I would say it started in 1974 with women’s music, because there were so few gay releases before then,” he explains. “Camp Records didn’t start a trend the way Olivia Records did in the mid-1970s, when they released wonderful recordings by Cris Williamson, Meg Christian, and a slew of other people. There was a distinct women’s music movement, but no comparable men’s music movement. Women had to fight harder for their rights, and they took advantage of the organization of the feminist movement to get the word out.”

When he connected with Garrett in 2012, Doyle thought he might know about this other label, too, given Garrett’s connections in the recording industry during the 1960s. But he had no knowledge of Camp Records. “Murray said other people had asked him about it at the time, and he didn’t know who was behind it,” Doyle adds. “I guess it’s not to be known.”

Four cover designs for Camp Records, including the full LP, “The Queen Is in the Closet” (top left) as well as three singles from the mid-1960s. Courtesy of J.D. Doyle. (click to enlarge)

(For more amazing tales of LGBTQ music, check out J.D. Doyle’s blog, Queer Music Heritage.)

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Singing the Lesbian Blues in 1920s Harlem

Singing the Lesbian Blues in 1920s Harlem Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male The Sissies, Hustlers, and Hair Fairies Whose Defiant Lives Paved the Way For Stonewall

The Sissies, Hustlers, and Hair Fairies Whose Defiant Lives Paved the Way For Stonewall RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file…

RecordsMore than a digitally perfect CD, and way more than a compressed audio file… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Well written. Things I did not know or were aware of.

Great story, the record cover for Queen is in the Closet looks like Andy Warhol’s early illustration style.

Interesting article. I wonder if “Lace Records” isn’t a play on “race records.”

I found this LP many years ago and have loved it since, and was JUST playing it for a friend a few days ago! When I got it, there was no info at all that I could find online – not even what year it was released. THANK YOU for this!

Hunter, Very good job here! Your research is Incredible!

Thomas(Brunswick).

Ta Ta, Hunter !!!!!

I volunteer at a resale/thrift store and just received the album in a donation, Mad about the Boy from Camp records. It was very difficult to find information about it. This article helped a lot. Thanks