Close-up of an Auzoux anatomic male manikin, made of hand-painted papier mâché, circa 1870. (Courtesy of the Bruce Museum)

The French physician Louis Auzoux was having trouble sourcing fresh cadavers. It was a common problem for doctors and medical students in the early 19th century, and if they couldn’t dissect the dead, how could they understand the inner workings of the human body? After touring a papier-mâché workshop, Auzoux began experimenting with the medium to create medical “manikins” or anatomical models—not to be confused with mannequins, the life-size human figures used to display clothes. Auzoux’s models had removable parts, making them ideal for teaching anatomy and sturdy enough to be used again and again. By 1827, he perfected the form (with a secret recipe) and, later, branched out into zoological figures. His factory, Maison Auzoux, made thousands of scientific models, which are now prized by collectors.

“The concept of sterilization changed the look of medical instruments forever.”

“It’s very correct, anatomically,” says Dr. M. Donald Blaufox of the three-quarter-size male Auzoux manikin that keeps him company in his study. To the untrained eye, the anatomical model looks raw, with its bulging eyeballs, exposed ribs, and wiry veins. But, Blaufox explains, it would have been “bright and shiny” when new, likely hand-painted by a woman in northern France sometime around 1870.

Like many pieces of 19th-century medical equipment, Blaufox’s Auzoux manikin was a finely wrought piece of art that we might find hard to square with today’s sterile hospital environment. Crafted of leather, wood, ivory, ebony, velvet, silk, and other extravagant materials, the tools of the physician’s trade were often beautiful—but, unbeknownst to them, they also harbored dangerous germs.

Mahogany box with glass medicine bottles, scales, and weights, circa 1850, which belonged to Dr. C. Winslow, a doctor and pharmacist in North Carolina. (From the M. Donald Blaufox Collection)

Blaufox’s interest in such items is both aesthetic and professional. Now the chairman emeritus of the department of nuclear medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, Blaufox, age 84, amassed a collection that once included about 1,000 medical artifacts. Though he has donated many pieces from his medical trove to numerous institutions, about 100 pieces from Blaufox’s collection have been reunited for an exhibition called “The Dawn of Modern Medicine,” which will be on display at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, through April 7, 2019.

The exhibition focuses on the decades between 1800 and 1920, which allows museum-goers to witness the development of “real” medicine, such as the first X-rays (1895), the first use of surgical anesthesia (1846), and the acceptance of Louis Pasteur’s Germ Theory (1880s). “So many things we take for granted were created at this time,” explains the museum’s curator of science, Dr. Daniel Ksepka. Because such inventions were new, they undoubtedly inspired fear in the Victorian patients introduced to them. For example, an early X-ray machine from 1900, with its bulbous glass tube, says Ksepka, “looks like something from a ‘Frankenstein’ movie!”

Blaufox’s beguiling collection all started with a set of apothecary drawers that he and his wife purchased about 40 years ago when furnishing their home. While seeking out some knickknacks to display on its shelves, he happened upon some old medicine bottles, which he began to collect here and there in his travels, enjoying the thrill of the hunt. During a trip to New Orleans to give a lecture, he used his free time to scout the city’s antiques district—he did that often while traveling for work—and noticed some bottles in a shop window.

Early X-ray tube and transformer, circa 1900. On loan from National Museum of Nuclear Science and History. (Courtesy of the Bruce Museum)

When he went in to take a closer look, the dealer asked if he also collected vintage medical instruments and showed him a single-bladed fleam, once used for bloodletting. “I bought it and then I started reading about it, picked up some medical-instrument catalogs, and thus began a long-term collecting career,” Blaufox says. “I just kept buying and building it up.”

At first, he focused on the topic of bloodletting, calling it a “fascinating area,” with acquisitions that included a mid-19th-century lancet with tortoiseshell covers, a circa-1780 pewter bleeding bowl, and several Victorian brass-and-glass cupping sets, often housed in velvet-lined rosewood or mahogany boxes, which were used to bleed or blister the skin.

The old-fashioned and sometimes deadly idea behind the practice of bloodletting was the pre-Germ Theory notion that illnesses were caused by an imbalance of the body’s “humors”—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Doctors thus attempted to restore balance by draining or purging the patient. (George Washington’s physicians inadvertently killed him using these misguided methods.) Blaufox’s late-18th-century creamware leech jar, incidentally one of his favorite pieces, also fits neatly into this category; live, blood-sucking leeches were routinely applied to patients as a restorative.

White creamware leech jar, circa 1780. The perforated top allowed the leeches to get air. (Courtesy of the Bruce Museum)

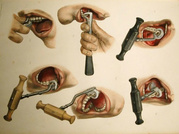

Another spine-chilling piece in his collection is a walnut chest containing dozens of ivory-handled surgeons’ tools, made in Paris around 1830 and used by early embryologist Martin St. Ange. It is a sumptuous set, with a red velvet interior and decorative instruments personalized with St. Ange’s initials. Those aesthetically pleasing features begin to drop off at the turn of the 20th century, once the medical community had finally given up on bloodletting and embraced Germ Theory. The surgical kit, Blaufox says, might be the rarest piece currently on display.

This exhibition arrives at a time when interest in medical history—which is entangled with questions of death, disease, and the ethics of health care—has surged. The hashtag #histmed pops up regularly on social media; the Morbid Anatomy project in Brooklyn produces popular lectures, exhibitions, and publications; the Mütter Museum, a collection of anatomical oddities, remains a popular attraction in Philadelphia. Pivotal developments in turn-of-the-century surgery even captured the imagination of Steven Soderbergh in his 2014-2015 Cinemax series “The Knick,” starring Clive Owen.

Surgeon’s kit of ivory-handled tools owned by early embryologist Martin St. Ange, made by Samson of Paris in 1830. (From the M. Donald Blaufox Collection)

For Blaufox, who runs the virtual Museum of Historical Medical Artifacts and also has a supplementary collection of more than 500 rare books, the primary motivation for collecting was to illustrate the history of medicine, with examples from a range of disciplines. In ophthalmology, he has a tray of glass eyes, circa 1880; in pharmacy, a set of 28 corked vials of various powdered remedies from 1900; and in quackery, a neat little device called a Baunscheidt Lebenswecker from 1870. The Lebenswecker (“life awakener”), developed by Carl Baunscheidt, basically pierced one’s skin with multiple needles, causing a rash of blisters, as a means of counter-irritation, a homeopathic technique (or a bogus one, depending upon whom you ask) predicated on the idea that you can reduce pain in one area of the body by inducing inflammation in another.

Because of his academic research interests, the largest parts of Blaufox’s collection were comprised of stethoscopes and sphygmomanometers (blood pressure gauges). He ended up writing two related books, Blood Pressure Measurement: An Illustrated History and An Ear to the Chest: The Evolution of the Stethoscope, in addition to many other books and peer-reviewed articles. One of those articles, in fact, recounted an acquisition from the early ’80s with an interesting twist: Blaufox purchased a sphygmograph (pulse monitor) from a European auction house, which had been part of a larger lot full of other random bits, and when the carton arrived, by mail, he was aghast to discover a vial inside labeled “Radium Compound,” which he tested and found to be radioactive. “Since I’m in nuclear medicine, it was handled properly,” he recalls. “It would have been terrible if it wound up with someone else!”

Cupping set with a vacuum pump of yellow enamel featuring gilt floral design, circa 1850. “This is one of the most ornate bleeding sets that I have ever seen,” writes Dr. Blaufox. (From the M. Donald Blaufox Collection)

Not surprisingly, Blaufox’s collection trails off after the one-two punch of Germ Theory and the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which began to regulate patent medicines and crank contraptions that yielded no real therapeutic results: Medical devices became utilitarian. The understanding that infection-causing germs lurked on a vaginal speculum made of boxwood and or an ebony-handled cautery (bonesaw) put the kibosh on ornamental instruments, although even the transitional items, such as the Lister Spray gadget from 1880, put form and function on the same footing. (The one on exhibit, Blaufox admits, is very elegant; they weren’t all this pretty.)

Dr. Joseph Lister, an English physician, is credited with introducing and advancing the notion of asepsis in the operating room. Unlike many doctors of the mid- and late-19th century, Lister believed that microorganisms in the air of the surgical theater were increasing the risk of post-operative infection. He therefore developed a carbolic acid solution and a heavy-duty spraying apparatus made from a brass boiler with weighted valves, rubber tubes, and a glass jar on a wooden base, to sterilize the air. Lindsey Fitzharris writes in her recent biography of Lister, “As comical as the mechanism was, the use of carbolic spray was a significant moment in medical history.” Indeed when Queen Victoria suffered from an orange-sized abscess in her armpit in 1871, it was Lister that she invited to operate on it. While Lister conducted the surgery on the queen, another eminent English physician, William Jenner, managed Lister’s cumbersome atomizer.

Lister started a revolution in surgery, and in time, his ideas about how infections spread were accepted. In the 20th century, a new material would take over the operating room: stainless steel. “The concept of sterilization changed the look of medical instruments forever,” Ksepka says. Those who visit “The Dawn of Modern Medicine,” he predicts, “may be impressed with the meticulous craftsmanship of early instruments but will surely be thankful they live in the modern era of anesthesia, antiseptics, and high-tech equipment.”

The Lister Spray machine, developed by Dr. Joseph Lister, disseminated a carbolic acid solution in the operating theater. This one was made by Arnold and Sons around 1880. (From the M. Donald Blaufox Collection, courtesy of the Dittrick Medical History Museum)

(Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of “Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places” and the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine. She writes about books and history for JSTOR Daily, Slate, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault)

How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault)

Sacred Anatomy: Slicing Open Wax Women in the Name of Science and God

Sacred Anatomy: Slicing Open Wax Women in the Name of Science and God How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault)

How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault) Bloodletting, Bone Brushes, and Tooth Keys: White-Knuckle Adventures in Early Dentistry

Bloodletting, Bone Brushes, and Tooth Keys: White-Knuckle Adventures in Early Dentistry PharmacyThe neighborhood drugstore, featuring a soda fountain and lunch counter, be…

PharmacyThe neighborhood drugstore, featuring a soda fountain and lunch counter, be… Medicine BottlesIn medieval Europe, apothecaries and alchemists appealed to their ailing cu…

Medicine BottlesIn medieval Europe, apothecaries and alchemists appealed to their ailing cu… Victorian EraThe Victorian Era, named after the prosperous and peaceful reign of England…

Victorian EraThe Victorian Era, named after the prosperous and peaceful reign of England… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Very interesting. Not too long ago, I posted something in a similar vein (no pun intended) called White’s Physiological Mannikin. See:

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/254675-whites-physiological-manikin?in=user

Also a bit creepy but used by medical schools to teach anatomy. Take a look.

Groveland.