In a country where institutionalized racism has been the norm for centuries, black barbershops remain an anomaly. Though initially blocked from serving black patrons, these businesses evolved into spaces where African Americans could freely socialize and discuss contemporary issues. While catering to certain hair types may have helped these businesses succeed, the real secret to their longevity is their continued social import. For many African Americans, getting a haircut is more than a commodity—it’s an experience that builds community and shapes political action. As both a proud symbol of African American entrepreneurship and a relic of an era when black labor exclusively benefitted whites, black barbershops provide a window into our nation’s complicated racial dynamics.

Quincy Mills, a professor of history at Vassar College, started looking closely at black barbershops when assisting Melissa Harris-Perry with research for her first book, Barbershops, Bibles, BET: Everyday Talk and Black Political Thought. Harris-Perry was investigating the ways African Americans developed their worldviews through collective conversation, specifically looking at three sectors: black churches, entertainment, and barbershops.

“As we know, the end of slavery didn’t necessarily mean the birth of freedom. It meant the birth of a new kind of bondage.”

Harris-Perry wanted to do a close study of barbershops, but was worried that as a woman, her presence would alter the nature of the space and its conversation. In her place, Mills observed the interactions of a barbershop on the South Side of Chicago four to five days a week during the summer of 2000. “As I sat there day in and day out, I couldn’t help but wonder how these spaces have been situated historically,” says Mills. “I had seen passing mentions of black barbershops in the literature on black urban history, but there weren’t any books on the topic. I wondered, ‘Were these shops the same in 1940? And what about 1840?'”

Mills spent the next decade researching the barbershop trade for his book, Cutting Along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, drawing fascinating connections between race, capitalism, and culture. We recently spoke with Mills about the roots of black barbershops and their relevance today.

Top: The Arthur Anderson Barber Shop in Mattoon, Illinois, which only served white customers, circa 1920. Via Eastern Illinois University. Above: Louis McDowell gives a young customer a high top fade in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1994. Via the Library of Congress.

Collectors Weekly: During the era of slavery, who worked as a barber?

Quincy Mills: In the South, barbers were both enslaved and free black men. There were white barbers in the North, but they were mostly immigrants, Irish and German and, later, Italian. Essentially, people associated barbering and other service work with unskilled labor, and white men positioned themselves as entitled to skilled jobs. They eschewed any notion of servility, so they didn’t want to work in service professions.

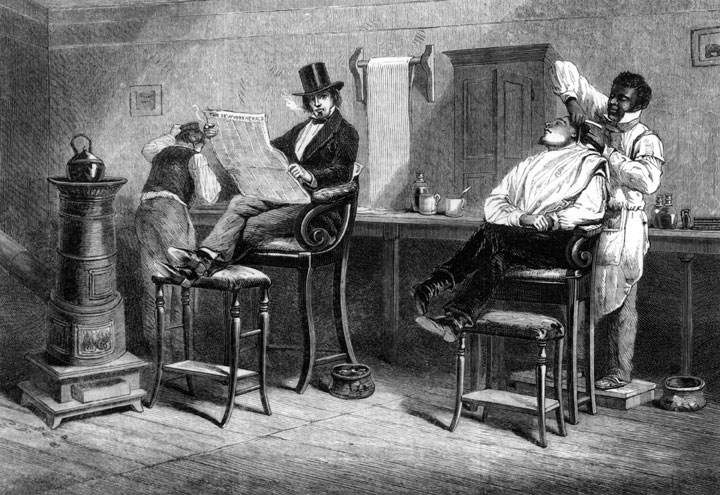

Before the Civil War, most black barbers explicitly groomed wealthy white men, like businessmen and politicians. Black customers were not allowed to get haircuts in these black-owned barbershops, mainly because white customers didn’t want black customers getting shaved next to them. That smacked too much of social equality, so barbers capitulated to the wishes of their white customers both in the North and the South.

Most black barbershops catered only to whites in the late 19th century. Via the Library of Congress.

You might wonder, “Where did black men get their hair cut?” They got haircuts on somebody’s front porch, or in the yard, or in all these other spaces that were not commercial. But here’s the limit of history’s lens: It’s also quite possible that black men came through these barbershops after hours, off the record.

“Barbering was a racialized profession, meaning it was viewed as an unskilled profession.”

I wrote about the case of a fugitive slave who recorded his travels through Kentucky, where he needed a place to hide out for the night, and explicitly looked for barbershops because he knew most barbers were black men. He found a barbershop, and as he’d guessed the barber was black, so he let him in, and immediately locked the door behind him. The fugitive’s name was John Brown, and he wrote that the barber said “You can stay for the night, but you have to be gone before morning because if anyone finds you here, it will shut up my shop.”

I take that to mean that if white folks found out he was harboring a fugitive slave, they wouldn’t patronize his business. But if the barber was willing to open his door after hours to this enslaved person on the run, it suggests that other barbers may have opened their doors after hours for all sorts of things. There aren’t enough sources to explore that in great detail, but I think it’s fascinating that they hint at it.

Collectors Weekly: How did the Civil War and abolition of slavery affect the American barbershop scene?

Mills: Before the Civil War, in the North, there was already freedom for blacks, so there was a discourse around respectable occupations for African Americans in this free society. For much of the antebellum period, folks like Frederick Douglass were writing against what they termed “color-line barbers,” who only allowed white customers in their shops. They argued that this smacked too much of slave labor, and if African Americans were going to be taken seriously, they needed occupations that were manly, respectable, and skilled. Douglass didn’t rail against black barbers in the South because he understood that they were in a slave society and couldn’t cater to African Americans. The system wouldn’t allow that to happen.

But after the Civil War, barbers in both the North and South were targeted by black communities for refusing to shave black men. In 1875, Congress passed a civil rights act as part of Reconstruction that guaranteed African Americans access to public places of accommodation. During Reconstruction, black barbers were coming to terms with this law, which was really meant to target white store owners, but it resulted in all sorts of protests against black barbershops who refused to serve the black community.

“It was at this barbershop that he gained a glimmer of awareness of the larger black freedom struggle.”

However, many of the barbers who only served white men were still deeply engaged in black communities. Take George Myers, who became a barber in the 1880s in Cleveland, Ohio. Myers was the barber to William McKinley before McKinley was elected president, as well as a prominent businessman named Marcus Hanna. Hanna was the Karl Rove of the late 19th century, helping McKinley get elected and raise funds. Hanna was an instrumental person for the Republican Party.

What’s interesting is that Hanna selected Myers to organize black voters in Cleveland and greater Ohio. Myers became the intermediary between African Americans and the Republican Party, so much so that when McKinley was elected, Myers got a flood of letters from African Americans in the South saying, “I heard that McKinley was elected president. Congratulations on all your work. Can you put in a good word for me for this job here in Mobile, Alabama?” People knew that Myers had the ear of the president, this proximity to the seat of power. Even though Myers only served white men in his shop, African Americans felt that if he could deliver those political resources to black communities, it wasn’t an issue.

This example extends to other prominent barbers like Alonzo Herndon in Atlanta, Georgia, and John Merrick in Durham, North Carolina. All three of these men were born in the 1850s and came to prominence in the 1880s and 1890s. Merrick and Herndon used the resources from their barbershops to found life insurance companies—Atlanta Life for Herndon and North Carolina Mutual for Merrick—that still exist today. That suggests the level of wealth these men had and that they were central figures of the black political class, bar none.

Folks like Merrick and Herndon used the economic resources from their barbershops to establish insurance companies because existing companies like MetLife weren’t insuring African Americans. They used their resources in support of black communities. Reconciling the individual and collective interests in the post-Civil War period was complicated.

Barber Alonzo Herndon founded the Atlanta Life Insurance Company in 1905. This photo shows the business and its staff, circa 1922.

Alonzo Herndon and John Merrick both came out of the South after the Civil War when cities like Atlanta and Durham emerged. Many barbers saw white industrialists relocating to particular cities and recognized a burgeoning and lucrative market. The only thing that changed in the South was that you now had more African Americans speaking out against black barbers who were exclusively shaving white men. The larger argument was that slavery didn’t exist anymore, so you were no longer bound to these kinds of demarcations. But as we know, the end of slavery didn’t necessarily mean the birth of freedom. It meant the birth of a new kind of bondage.

We know there wasn’t a lot of money in the post-emancipation South because of the war’s destruction. We know that African Americans were pushed into sharecropping situations, which meant perpetual debt and no spending money. As a result, black barbers were making problematic yet rationalized decisions about their clientele.

Collectors Weekly: Did African American activists promote different careers in lieu of barbering?

Mills: Yes, it was all about the mechanical trades or carpentry, obviously skilled positions. But that term needs to be taken with a grain of salt. I don’t know if you’ve ever used a straight razor, but you know it takes a lot of skill because you can easily cut somebody’s throat with it. We also know that the social organization of labor was very racialized. So while it took a lot of skill to use a straight razor, the sheer fact that most barbers were black also meant that barbering was a racialized profession, meaning it was viewed as an unskilled profession. It was that simple.

Black activists felt that if barbers continued to shave white men, then they would continue to be seen as inferior, as servants in this dependent position. Many of the arguments about leaving barbering and other service occupations were about how others would view one’s labor. I think that that sentiment still exists with us, which is why there’s all this contemporary talk about who’s going to do lawn service work, which is also very racialized. “If we cut off immigration, who’s going to cut my grass?” It suggests there’s no clout in saying, “I cut grass for a living,” or saying, “I work at McDonald’s.” Even when there are very few jobs, many workers don’t want the kind of jobs society deems degrading.

A card for the Palace Barbershop, circa 1920s, which served the local black community in Durham, North Carolina.

Collectors Weekly: What was the effect of the “professionalization” movement?

Mills: Part of professionalizing the trade meant to re-skill the trade, an obviously racialized project to make barbering a more attractive field for whites to enter. One major marker was the founding of the Journeymen Barbers’ International Union of America, mostly organized by German barbers in the 1890s. Now, unlike native whites, German immigrants didn’t mind being barbers. They had been barbers in Europe. The Irish and Italians didn’t care about the racial stigma of barbering either. But it was clear that in order to make headway with the wealthy white clientele served by black barbers, German barbers had to make some bold moves, and organizing the union was one way they did this.

“While it might seem like they were fighting for African Americans’ rights to a trade, they were actually fighting for their own right to keep black servants.”

In the 1890s, the union pushed for licensing laws to regulate who could become a barber. This was part of a larger professionalization movement, the same moment that the American Bar Association was established to determine how one would become a lawyer and the American Medical Association was established to determine how one would become a doctor. The barber’s union lobbied various state legislatures to pass laws requiring a degree from a barber college. And as you might have guessed, blacks were not admitted to these barber colleges.

These laws meant that you couldn’t just pick up some scissors, hang out a shingle, and say I’m open for business. You had to know the anatomy of the body and something about disease—you had to be a scientist, if you will. If there was ever a moment of a nostalgia for the days of the medieval barber surgeon, this was that moment. This was when we started seeing barbering textbooks with “science” and “anatomy” in their titles.

The union attached itself to the sanitation movement as well. In order to convince legislatures that these bills were worthy of passing, they had to say, “We’re trying to protect the public. What would happen if someone wandered into a dirty barbershop and got some kind of disease? We don’t want that, do we?” Black barbers recognized this as an effort to push them out of the trade, so they were skeptical.

Left, a barber’s union card from the late 1890s, and right, another from the 1940s. Unions like these pushed for licensing laws that attempted to prevent black barbers from entering the field.

Collectors Weekly: Was there any evidence of people getting diseases during a haircut?

Mills: Absolutely not, so little that state health departments were baffled at these bills, most of which did not consult them. They were like, “Wait, you want to pass a health law without the consultation of the health department?” There were also restrictions like in Richmond, Virginia, where in order to get a license, barbers had to be tested for syphilis. You get syphilis through sex, not a haircut, but there was a larger pattern of segregating blacks based on the unfounded threat of giving whites syphilis. There are some things, like head lice, that can be passed at a barbershop, but they weren’t talking intelligently about any real health concerns. It was about competition for market share.

In some states like Minnesota, they passed licensing laws fairly quickly. But in states like Ohio and Virginia it took a long time. From 1902 to 1933, the Ohio licensing bill kept getting rejected largely because of the connections of McKinley’s barber, George Myers. He had a lot of political clout, and said, “Look, if you pass this bill, I will be sure that blacks do not vote the Republican ticket.” He didn’t really have that kind of power over black votes, but he used this perception of power. That licensing bill didn’t get passed until after Myers died.

The Virginia bill kept getting rejected largely because whites opposed it. They believed black barbers who said this was a move to push them out of the trade, and whites in Virginia didn’t want to lose their black barbers. For them, having a black barber was a vestige of the Old South, like having black servants. While it might seem like they were fighting for African Americans’ rights to a trade, they were actually fighting for their own right to keep black servants. The story’s a bit complicated in that way.

Collectors Weekly: Did the professionalization movement push black barbers to cater exclusively to black customers?

Mills: In terms of black barbershops opening in black communities, by and large, it wasn’t so much as a result of the union efforts. By the 1890s, you have a new generation of African Americans who had been born and came of age after the Civil War. They were not as connected to white communities as their predecessors were. They didn’t enter barbering grooming white men. Instead, they explicitly decided to open barbershops in black communities. This is, obviously, the same time that Jim Crow laws were on the rise, so that was happening in parallel.

It was a moment when African Americans turned inward to consider the organization of black communities that were becoming increasingly segregated and surveyed, and facing more racial violence. They turned inward to think about how to respond to Jim Crow, but also to engage in the self-reflective work that produced black cultural movements.

The Golden West Hotel in Portland, Oregon, opened in 1906 to serve the city’s booming black population. Waldo Bogle’s barbershop was one of the hotel’s various businesses.

Collectors Weekly: In your book, you call barbershops “private spaces in the public sphere.” Can you explain that concept?

Mills: Barbershops are commercial spaces, so anyone can technically go inside them—it’s not like somebody’s home where you have to get permission to enter. But they’re private in that there’s an expectation that what happens in there, stays there. Black barbershops are private because whites wouldn’t be around, so their patrons wouldn’t be surveilled. It wasn’t like a public park or a street corner.

In many barbershops, for example, the nature of the conversation changes when women enter. Sometimes it changes in a paternalistic way like, “There’s a lady in here, and we have to be respectful, so don’t curse.” There’s a certain type of respect, which is really about the production of masculinity, and how men think they should perform their own masculinity around other men.

The other side of the public-private designation is that while barbershops are public in terms of collective conversation, this takes place within a private business. We tend to forget that the market economy is still central to the barbershop’s existence. The barber has to turn some kind of profit. The needs of a private business are balanced with the needs of this collective dialogue.

Barbers Pete Boyd and Johnny Gator cut hair in Gator’s barbershop circa 1950, while female relatives socialize in the background. Photo by Charles “Teenie” Harris, via the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Collectors Weekly: Did these black commercial spaces become sites for political action and activism?

Mills: Yes, definitely. With the rise of Jim Crow, public spaces were becoming less accessible to African Americans, so it helped that places like black churches, black barbershops, and, later on, black beauty shops and other businesses provided spaces where African Americans could safely gather, talk, and organize.

This 1960s flyer from the University of Illinois calls for students to urge barbers to serve all patrons or else boycott them.

Now, I wouldn’t put black barbershops on the same level as the church. It’s very well-documented that the black church was central to Civil Rights organizing, and that’s because they were much bigger spaces. You can fit hundreds of people in a church, while you might only get five or six people meeting in a barbershop.

But there are a number of cases where activists retreated to a barbershop to plan a particular campaign, and there are tons of examples of African Americans coming to consciousness in barbershops. Black newspapers were available in barbershops and many barbers were quite politically active, so they would provide their own literature and reading materials, whether about the Communist Party or registering to vote.

Stokely Carmichael, who would go on to be chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was first exposed to activism at his regular barbershop. When his family moved to the Bronx, the local barbers were Irish and couldn’t cut his hair, so Carmichael wound up going to Harlem every week to get his hair cut. He explained in his autobiography how it was in this Harlem barbershop that he learned about the Brown v. Board of Education decision and black activism. It was at this barbershop that he gained a glimmer of awareness of the larger black freedom struggle.

Collectors Weekly: Did segregation laws spur the growth of black barbershops?

Mills: Actually, I think that even if Jim Crow had not come to be, these shops would still have functioned the same way because of the needs of hair type and black cultural life. Hair doesn’t have a race, meaning there’s no such thing as black hair or white hair, but there are different hair types. You can cut straight hair with scissors, but if someone has curly or coarse hair, you can’t just use scissors because the hair’s going to curl up and you won’t get an even cut. Hair type matters because you have to know how to cut my hair for me to actually go to your shop.

There’s also a level of trust in the barbershop as a whole because of this larger camaraderie happening in that space. If someone thinks of a haircut as a commodity, then it doesn’t matter who cuts their hair—they can go to a Supercuts in New York, and then go to a different Supercuts in D.C. next week. However, I think many African Americans don’t view haircuts as commodities but as a more personal service. That’s why I argue that barbershops serve a larger function and were not just a response to Jim Crow. They were central to the production of black identity.

During the era of desegregation, and even now, black barbershops, beauty shops, and the churches are still black spaces. Obviously, African Americans attend all sorts of churches and beauty shops, but those catering to the black community are still largely separate. And that is essentially because the production of black culture happens in these spaces.

A crowd gathers outside a store and barbershop in Union Point, Georgia, circa 1941. Photo by Jack Delano, via the Library of Congress.

Collectors Weekly: How is barbering central to black communities today?

Mills: I think it’s an important trade for many black communities largely because there are still few barriers to entry. It’s not like opening a restaurant, where you need a substantial amount of capital. If you want to be a barber, you go to barber college, get your license, and you’re set. It’s still an open avenue for many folks, and people will always need haircuts. Styles may change and some people will let their hair grow out, but I think barbers will always be in demand.

However, the nature of barbershops is changing, and I think technology is at work here. I’ve found that when folks are waiting around in barbershops, they’re much more likely to be on their cell phones than engaging with other people. That’s a larger societal issue, of course. We are tethered to our phones in ways that are scary. The generation of men in their 50s, 60s, and older, still goes to barbershops to hang out and talk, and they’re not attached to their phones the way my generation might be.

I suspect that in a place like Detroit, for example, a city that is facing massive bankruptcy, dislocation, etc., places like barbershops are actually quite critical at this moment. They provide this connective tissue amid all the reports of violence, disinvestment, and decline. I suspect that barbershops are providing a space where folks can rail against that narrative and engage with each other, where they can keep community ties together.

Louis Armstrong gets a haircut in his local barbershop in Queens, New York, circa 1965. Via “LIFE” Magazine.

Collectors Weekly: Why is there still such a strong racial divide in American barbershops?

Mills: There’s some merit to the argument that you need open spaces where folks from various nationalities or races can get together and talk about weighty matters. We need to come together to discuss this stuff. But I think barbershops are critical because they are spaces of “willing congregation,” as I like to call them, rather than rigidly segregated spaces. They’re important today because we know that black communities are still very marginalized.

During the recession, when the national unemployment rate was upwards of 8 or 9 percent, the black unemployment rate was double that, around 17 or 18 percent. Any student would look at those numbers and say, “Something’s wrong with this. Why is this double?” But the Obama administration felt constrained to talk about the issue from that perspective. Frankly, it doesn’t matter who the 18 percent was: They could’ve been white, Latino, Asian, anyone. That number shows huge inequality and disparity. We can also talk about the incarceration rate; there’s clearly a disparity in who’s incarcerated. But it takes a lot just to point out those disparities to the larger public, much less to talk about the reasons why.

That’s not to say at all black folks think the same thing—in fact, you get lots of debates and people disagreeing in barbershops. But you don’t have to do the heavy work of convincing people of the obvious, of saying that this topic matters. That’s why spaces like black barbershops are important, because you can cut through that jazz and get to the heart of what we should do about these issues.

Louis McDowell demonstrates how to sharpen a straight razor at his shop in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1994. Via the Library of Congress.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums? The Sharecropper's Daughter Who Made Black Women Proud of Their Hair

The Sharecropper's Daughter Who Made Black Women Proud of Their Hair Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and …

Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and … RazorsAlthough the clean-shaven look has been in style periodically since at leas…

RazorsAlthough the clean-shaven look has been in style periodically since at leas… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article and a beautiful portrayal of an important American institution. I love the concept of “willing congregation” and grass roots organizing in the barber shop.

This article does the important work of informing us all of a forgotten past and the road we have traveled to get where we are. Our enthusiasm for the ideals expressed in the documents that founded the USA should be tempered by the very real stories like this one, that let us know degree to which those ideals were and actually are lived in this country. If we want the future to be more than a rerun of the past, we have to read, understand and act! Well one Hunter!

Very interesting perspective on the black public sphere. I haven’t read Mills’ book, but Barbershops, Bibles & BET is a great source to learn more about this topic. Also, Melissa Harris-Lacewell is the author, not Harris-Perry .

Nevermind! Didn’t realize she changed her name.

I’m buying the book. Barbershops are an institution or social awareness and change regardless of the community. I’m 67 and from Denver, Colorado. Growing up a visit to the barbershop was always informatiive, entertaining, most importantly, they were enlightening. Barbershops of my generation in the black community, regardless of city, were a “right of passage” for a young black kid. As with so many oither things in the black community, you never know how important something is until you no longer have that “something.” I now live in the Wash, DC area and have a barbershop that beckons back to the barbershops of my youth and this shop is recognized as a pillar in my community. I hope articles like this are read by youngsters in their “right of passage!”

this article is lovely, really helped me to prepare for my presentation.

This article is very informing, ill have to disagree with the author, on the topic of women in the barbershop , im a Female Master Barber and Instructor with the state of Tenn, I fill as she being a spectator of the environment that her way of thinking was altered.

This article was helpful in expanding my research for a documentary I am producing that examines the rise of black business in America. Business in the Black check out the Facebook page it’s due out this summer.

Saw a article you might be interested in.

http://www.citylab.com/cityfixer/2015/04/getting-african-american-boys-to-read-with-barbershop-books/390405/

Great read! I am big on history and I cut hair myself so this was quite inspirational. I am also a visual artist and I was curating an exhibition next month. The concept focus around the history of black barbershops, black barbers & inventors, the therapeutic aspect of grooming, hair artistry, male hygiene and overall therapy that lies behind it all. The photos you have would fit great in the exhibition(it’s totally fine if not). The exhibition will be hosted at Off the Wall Arts in Memphis, TN.

Your article is special to me because my freat grandfather , Nathaniel C. Lewis owned a Barber Shop in Summit, Akron Ohio around 1870. The address was 119 Furnace st. Can you direct me to any information, images or stories. He was African American. I am doing family research to pass on to my great grand children. Best Wishes Joan Lewis