If the acclaimed 20th-century existential phenomenologist Martin Heidegger had written a book about garbage cans, it might read like portions of “The Paradox of the Waste Paper Basket” by Jos Legrand. Published earlier this year in Maastricht, Netherlands, where Legrand lives, Paradox is a concise history of the trash receptacles used in American offices between 1870 and 1930. You know, exactly the sort of thing you’d expect a retired Dutch art-history teacher to be passionate about.

“A waste bin is a jelled temporality.”

As it turns out, Legrand has long been passionate about all sorts of old office equipment, particularly typewriters, which led his to his interest in the containers that crumpled up sheets of typewriter paper were routinely tossed into. “No one had ever paid any attention to the waste paper basket,” Legrand explained recently via email (he does not own a phone). “For me, this was a challenge rather than a discouragement.”

Legrand’s unnumbered book (it’s about 50 pages long) arrives as the zeitgeist, as Heidegger probably would have put it, is unusually preoccupied with garbage cans. In many municipalities across the United States, one must practically have a degree in waste management before tossing one’s refuse in the trash. There’s a blue can for recyclables, a green one for compostables, and if your garbage is truly garbage, it goes in the black can, depending, of course, on where you live (which can make traveling complicated, but I digress…).

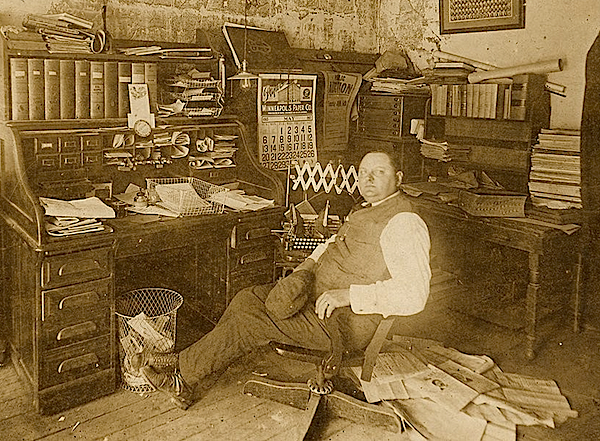

Top: Charles A. Reil, editor and publisher of the “Waconia Patriot” in Waconia, Minnesota, 1917. Photo via Early Office Museum. Above: Workers computing bonuses for soldiers who fought in World War I. Photo via the Library of Congress.

Happily for us, Legrand digresses, too, devoting a fair amount of his book to the “European” (his word) perspective on the great American waste paper basket. “Mistakes are as old as the office,” he writes, “and therefore the waste bin is the symbol of the ‘officium imperfectum,’ the imperfect office.” This, Legrand believes, is just one of several paradoxes of the office waste paper basket.

Until I read Paradox, I had not considered the possibility that waste paper baskets could be imbued with paradox, but Legrand has convinced me. In a perfect world, he postulates, the office is a place where work is performed efficiently and at high speed. But the presence of a waste paper basket is proof of the opposite condition, since it’s designed to be filled with failures. Thus, as Legrand puts it, a waste bin is “a jelled temporality.”

“As long as the bin hasn’t been emptied,” he elaborates, “its contents are the physical rendering of our thinking, our doubts, and ultimately the rejection of everything that doesn’t fit into a certain system. Once emptied, that visibility is over, or, as Heidegger would say, the truth is hidden again.”

In 1917, coffee importer A.C. Israel of New Orleans had a ticker that spat out the latest coffee prices. The ticker’s overflow was captured in a tall wicker waste paper basket. Photo via Early Office Museum.

This duality accounts for the waste paper basket’s unique place in our culture. For example, in order to delete files on our computers, we must drag them to a trash can or a recycle bin—from garbage comes order, to paraphrase Nietzsche. “The basket was the antipode of bureaucracy and neatness,” Legrand writes in his book, “and therefore at the same time its icon.”

As one might expect, the advent of the waste paper basket in the 19th century coincided with the increased use of paper by new business entities, as well as the government bureaucracies designed to regulate them. In the early part of the century, paper had been expensive, but advances in paper production made this once-precious commodity inexpensive enough to waste.

Still, “waste not, want not,” as the pre-Heidegger proverb goes, which is why by the end of the 19th century, office waste paper baskets were seen less as convenient containers for trash on its way to incinerators than as holding bins for precious resources on their way to the pulp mill—once their paper contents had been separated from the used typewriter ribbons and orange peels that also found their way into the same bin, that is. According to Legrand’s research, prior to World War I in New York City alone, the paper-recycling industry employed some 40,000 people, including a small army of pushcart entrepreneurs, who sorted and then moved more than 100,000 tons of waste paper per week.

For Legrand, this is yet another waste paper basket paradox—much of the waste paper in waste paper baskets was not wasted at all.

Henry Leland (right) and Robert Faulconer (left) of Leland & Faulconer, which became Cadillac, circa 1903, each with his own empty wicker waste basket. Photo via the Library of Congress.

More prosaically, in Paradox we also learn that some of the earliest office waste paper baskets of the 19th century were made of rattan (derived from parts of palm trees) and imported from China. Others were woven from wicker (plaited lengths of willow or osier), shipped from Germany and then assembled by German craftsmen in the United States. That led to the import of German baskets to the United States, “Direct from the great basket industries along the beautiful valley of the Thueringer Forests,” as one ad from 1905 read. World War I, however, ended such Teutonic imports, which allowed a willow-weaving industry to blossom in Baltimore and parts of upstate New York.

Standard wicker office baskets consisted of a round base (relatively few were square) anchoring vertical, plaited willow stakes, each of which was held an equal distance apart from the next by two to four horizontal rings. Usually a twined ring of heavier willow or rattan would crown the basket’s opening, providing structural support for the basket overall, while also giving basket craftsmen an armature for handles. Wicker office baskets are distinctive for their open architecture, revealing the crumpled first drafts of letters or expired contracts inside, but some wicker or rattan baskets were woven tight, keeping the accumulation of a day’s failures discretely hidden from view.

For Legrand, the predominance of the wicker baskets that he encountered in the course of reviewing more than 600 photographs of waste baskets in office settings (he found more than a quarter of these at the excellent Early Office Museum) was a big surprise. “I was struck by how long traditional basketry was used in offices,” he told me. “Modern materials such as fibre played a marginal role. It is a kind of weird to see the most up-to-date bookkeeping machine or telephone beside a traditional woven basket.”

Early 20th-century advertisements for Nemco and Dan-dee waste baskets (click to expand). Photos via Urban Remains.

This reliance on natural materials is doubly surprising when you consider how easily wicker baskets burned. Cigars or matches carelessly tossed in bone-dry wicker baskets full of paper regularly set off infernos, sometimes burning entire buildings to the ground. Thus, a market for metal waste baskets developed, some of which touted their resistance to flames. For example, in 1914, the Metal Office Furniture Company patented a fireproof waste basket called the Victor that was made of sheets of steel—oddly to contemporary eyes, it was painted to resemble wood, since that was still the prevailing aesthetic of the day.

In the first decades of the 20th century, other companies like Andrews Wire and Iron Works of Rockford, Illinois, and Massillon Wire Basket Co. of Ohio produced, as their names suggest, wire baskets, while in the 1920s, Nemco (Northwestern Expanded Metal Company) of Chicago made wire-like baskets that were actually made of perforated metal sheets that resembled wire when mechanically expanded and shaped. Nemco baskets were famously flared at the top, and sometimes had bulbous middles, giving them what Legrand calls a “foxglove” appearance, named for the shape of the flower. In keeping of the office décor of that era, Nemco baskets were dark, enameled in maroon or olive green.

Since they could not promise to be fireproof, “vulcanized” fibre waste baskets were sold on the basis of their economy and ability to contain a mess (click to expand). Photos via Jos Legrand.

Concurrently with wire and expanded baskets were solid metal baskets such as the Dan-dee, which was patented in 1909 by Erie Art Metal Co. of Pennsylvania. With narrow, vertical openings in its side, baskets like the Dan-dee did a better job of containing trash than wire or wicker baskets. Since early 20th-century offices did not have the blue, green, and black containers so many of us are familiar with today, just about everything ended up in the same bin. Baskets like the Dan-dee kept this dog’s breakfast of trash mostly out of sight.

Finally, waste paper baskets were also made out of paper, employing a process by which paper fibre was “vulcanized” to make it fire resistant, though not fireproof, which, according to Legrand’s research, these products were not. Vulcanized fibre was not new: it had been used in eyeglass frames since the 1860s, but it didn’t get pressed into service for trash receptacles until the 1880s. Burma brown was the color given for vulcanized fibre that was supposed to resemble leather, and different manufacturers made up different brand names for their products. American Vulcanized Fibre Co. of Wilmington, Delaware, which patented a special riveting machine for its fibre baskets, sold the Vul-Cot, while the C. Spiro Mfg. Co. of New York marketed its vulcanized fibre waste baskets as the Uniq. Like metal baskets such as the Dan-dee, inexpensive fibre baskets offered office managers the opportunity to reduce visual clutter, and were advertised accordingly.

Typical floor companions in offices of the 1920s were waste baskets and spittoons, as seen in this photograph taken in 1929. Photo via Early Office Museum.

Looking at some of the photos in Legrand’s book and at sites like the Early Office Museum, you get the feeling that a lot of these offices needed all the help they could get. There’s the 1917 photograph of Charles A. Reil, editor and publisher of the “Waconia Patriot” in Waconia, Minnesota, a wire waste basket at his feet, a cascading pile of even more paper behind him. In another photo, this one from 1929, one can see a round, sheet-metal waste bin on the floor to the right of an office chair, with a spittoon to the chair’s left.

Now that the Thomas J. Watson Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has purchased a copy of Paradox, perhaps Legrand will turn his attention to spittoons next? “My last article was about McGill fasteners and punchers,” he corrects me via email, referring to his interest in the inventions of one George W. McGill, who, in 1866, patented a “metallic paper fastener,” the precursor to the stapler. “But typewriters are my passion. Right now I am writing a book about the early writing balls of Danish pastor Rasmus-Malling Hansen. They appeared between 1870 and 1875.”

Today, very few of us would purchase a typewriter like a writing ball for anything other than decoration, even though many more of us know how to type than did back in the 1870s. That’s definitely ironic, but I’ll leave it to Legrand to tell me if it’s a full-fledged paradox.

(To order a copy of The Paradox of the Waste Paper Basket, email Jos Legrand at jjlegrand@hetnet.nl with “wpb” in the subject line.)

Could There Be a Treasure in Your Toilet?

Could There Be a Treasure in Your Toilet?

Dear Tom Hanks: Have We Got a Typewriter for You!

Dear Tom Hanks: Have We Got a Typewriter for You! Could There Be a Treasure in Your Toilet?

Could There Be a Treasure in Your Toilet? A Filthy History: When New Yorkers Lived Knee-Deep in Trash

A Filthy History: When New Yorkers Lived Knee-Deep in Trash BasketsIt’s easy to make the case for baskets. After all, they are one of humankin…

BasketsIt’s easy to make the case for baskets. After all, they are one of humankin… Office AntiquesToday, when most of us head into the office, our quiet digital tools are re…

Office AntiquesToday, when most of us head into the office, our quiet digital tools are re… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Viewing an office wastebasket as evidence of mistakes and as “the antipode of bureaucracy and neatness” is at best a partial grasp of what it does, and at worst a misunderstanding of its real function in bureaucratic efficiency.

The basket is not used only for discarding mistakes. Consider its role in processing incoming mail; letters received are reviewed and those not deemed necessary to keep on file are placed in it. Input –> evaluation –> retention or disposal. If that’s not more rational than holding onto excess paper, then I’m missing something here.

“I bought a wastepaper basket and carried it home in a paper bag. And when I got home, I put the bag in the wastepaper basket.”

— Lily Tomlin

It’s odd that you assume everyone uses some apple-brand computer.

I assure you, quite sincerely, that you are a minority in that respect.

Johannes Brahms told many friends and acquaintances that the most important piece of furniture in his apartment was the wastebasket. The lid on it was to be open at all times, he instructed his housekeeper, Frau Truxa.

Brahms destroyed many of his works, including 2/3rds of his chamber music efforts, these not being up to snuff. The wastebasket was very rarely empty, I imagine.

I have a metal waste paper basket very similar to the one shown. Mine is embossed PENN ART STEEL WKS, ERIE. PA

It has a 2 colored striped design like the one shown, although i would call it patina, not paint. The cut-outs are just along the top and are diamond shaped. Its really beautiful after applying a penetrating product on it, just enough to bring out the gorgeous colors and aged patina.. I would love to hear from you if yoh have any idea of age, value, etc. Thanks for reading.. I would post a picture, but im not seeing a way to do that here. So https://photos.app.goo.gl/qzbmdTbX7q4X0HQ82 is the link to view the album. Thank you for reading. Dayna767@gmail.comdayna767@gmail.com

In the Dominican Republic a trash can is is called a “Safecon” The commonly accepted story of how this non-standard Spanish word came to be used is that US occupying forces used a receptacle from the Safety Can Company.