This is an article about the Huguenot silversmiths – French refugees who traveled to America in the 17th and 18th centuries – and their ability to create works in the popular styles of the times. It originally appeared in the July 1939 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

To those countries that afford asylum to the victims, national persecutions frequently reward the befrienders to a far greater degree than was anticipated. America was largely colonized by people fleeing from religious, economic, or political oppression, and in the latter part of the 17th Century, England absorbed several thousand Huguenot refugees and soon left her neighbor, who cast them out, far behind in commercial and industrial enterprise.

By Patriot Paul Revere: This domed tankard, with pineapple finial, reflects in shape and proportion the classical influence. Paul Revere, 1735-1818, worked in Boston until about 1800, when he forsook silversmithing for copper and brass founding.

These Huguenots lived largely in the provincial cities where they virtually controlled such industries as papermaking, silk and woolen weaving, stocking and glove-making and, being essentially merchant minded, the French export trade. Also among them were a sufficient number of silversmiths to leave definite impress on both English and American craftsmanship of the 18th Century.

It is amazing how little the essential features of persecution vary through the ages. A page from the 17th Century or from the 20th, the unlovely story runs much the same. First, a series of oppressive measures curtailing civic liberty; then religious intolerance, culminating, in the case of the Huguenots, in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Finally, seizure of property and extreme cruelty whereby, harried beyond endurance, they were yet forbidden to leave the country. But, of course, they went just the same. The French seaports were closed to them and outgoing boats were searched, but there were still land borders and across them several hundred thousand managed to escape over the years, to Holland, Switzerland, the German principalities, and thence to England and America.

Silver-Gilt Cup by Paul Lamerie: Lamerie was the most outstanding Huguenot craftsman working in London. This cup shows his most ornate work in the rococo style.

The reason for the considerable number of silversmiths among them was probably as much economic as religious. The wars of Louis XIV and the building of his palace at Versailles had been military and architectural extravagances costly almost to the point of ruin. Private purses were so depleted by taxes that clients for fine plate were few. And even had there been orders, material for making pieces was almost non-existent since Louis had ordered all plate melted down to furnish currency for his ventures.

So, many a silversmith found himself out of work and naturally moved on to greener pastures. In fact, we find them in England even before 1685. Granted there was a little trade jealousy at first, but it soon disappeared because of the national sympathy evoked by religious persecution, a sympathy all the more fervent because of the incidents leading to the Revolution of 1688. America, already a refuge for the oppressed, proved fertile territory for the many Huguenot émigrés who presently arrived.

So England gained such masters of their craft as Paul Lamerie, Pierre Platel, and Lewis Mattayer; while American silversmithing was enriched by such men as Bartholomew Le Roux, Cesar Ghiselin, Rene Grignon, Simeon Soumain, Thauvet Besley, Paul Revere, and many others mostly found in the larger centers.

By Daniel Christian Fueter: This Huguenot craftsman worked in New York 1754-1770. Earlier, he was in London where his touch-mark was registered with the Goldsmiths’ Company. In 1770, he returned to Switzerland, leaving his son Lewis to continue in New York.

All things considered, one would expect to find these Huguenot master craftsmen with registered marks re-establishing themselves in London and various American centers, but careful study of records does not disclose a single name that can with certainty be considered that of a master workman with a recorded mark in his native France. On the contrary, the refugee craftsmen seem to have been journeymen who rose to enough prominence for a registered mark only after they settled in England, and some of them, like the great Paul Lamerie, actually learned their trade there.

In America, although there was a distinguished group of Huguenot silversmiths from shortly after 1700, we cannot be sure that any of them came directly from France. Some arrived here from the Low Countries; others came by way of London.

Otto de Parisien migrated from Berlin; Daniel Christian Fueter seems to have started from Switzerland, worked a few years in London where he had his mark, and then moved on to New York, where he stayed until the gathering war clouds of the American Revolution influenced his return in 1770 to the peace of Switzerland. His son Lewis remained in the New World.

Porringer by Paul Revere I: He was apprenticed to John Coney. The handle of this piece is typical in shape and design of those used by New England silversmiths of the period.

George Ridout, who was working in New York in 1745, had a London mark in 1743. Bartholomew Le Roux, founder of the Le Roux dynasty of New York Huguenot silversmiths, came to America from London about 1690. His son Charles was at one time official silversmith to New York City. One of Bartholomew’s apprentices was Peter Van Dyke whom he allowed his daughter Rachael to marry, an unusual concession for the clannish Huguenots of the 18th Century.

Johannis Nys was born in Holland; Simeon Soumain in England. Cesar Ghiselin, the first silversmith to ply his trade in Philadelphia, also came from England, as did Appollos Revoire, who was born on the Island of Guernsey, came to America as a boy and learned his trade in Boston, where he was apprenticed to John Coney. He was among the first to Anglicise his name. Thus it became Paul Revere, so well known through his son Paul II in both American history and silvermaking.

Two-Handled Bowl by Soumain: Simeon Soumain worked in New York circa 1705-1750. In design, this bowl shows the Dutch influence strongly. Its original owners were Hendrick and Catalina Remsen, married about 1730.

Representative of the second or third generation of Huguenot silversmiths in this country was Elias Pelletreau of Southampton, Long Island, whose apprenticeship was served under Simeon Soumain and whose son and grandson were also Long Island silversmiths.

Huguenot silversmiths worked in practically all the centers of wealth along the Atlantic Seaboard from Boston to Charleston, South Carolina. The greatest number were, of course, in Boston, New York and Philadelphia. Not because of a special concentration of Huguenots in those places, but because they naturally attracted more followers of the craft than smaller communities.

Among the earliest to reach America was Captain Rene Grignon, who settled in Oxford, Massachusetts, in 1691; five years later he moved to Boston and in 1707 to Norwich, Connecticut, where he died in 1715. Among his apprentices was another of the same strain, Daniel Deshon, to whom he bequeathed his silversmithing tools.

Tea Set by Peter de Riemer: These three pieces, with rococo decoration, are believed to comprise the first tea service made in New York. They bear the Van Rensselaer crest and the initials of Philip Schuyler Van Rensselaer. De Riemer was born in New York in 1738, became a freeman in 1769, and died in 1814.

Another who moved about was Peter Feurt, who worked first in New York and then in Boston, where he died in 1737. Cesar Ghiselin deserted Philadelphia for Annapolis, Maryland, about 1715, where he remained not quite fifteen years and then returned to Philadelphia for the remainder of his life.

His silver is excessively rare, only about two large pieces being known. These are an alms basin and a beaker belonging to Christ Church, Philadelphia, for which they were made as the gift of Margaret Tresse. In the light of the exhibition of French domestic silver, held at the Metropolitan Museum last summer, both are much simpler than those current at the time in France.

By Cesar Ghiselin: In their simplicity, this beaker and alms basin are typical of the 17th Century. Ghiselin was born in England, reached Philadelphia by 1693, and died in 1733, having worked for some years in Annapolis, Maryland.

Because these Huguenot silversmiths moved from one place to another as opportunities for better business dictated, and because there was a general tendency in the second and third generations either to Anglicise their family names or drop them entirely and substitute English translations for them, I doubt if it will ever be possible to compile a complete list of those who worked in America. Also, those who became followers of the craft in the third or even fourth generations of course worked entirely in the American tradition.

Studying known examples of the early Huguenot silversmiths who worked in America, it is noticeable that their work is usually very simple and lacks the ornate decoration and details of execution characteristic of French silver during the first part of the 18th Century.

A New York Porringer: Made by John Hastier ,who worked circa 1725-1791. The design of the handle is typical of the form used by 18th-Century New York silversmiths. The porringer bears on the handle the initials P S to E S.

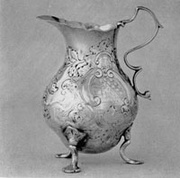

One or two exceptions to this include the pair of beautifully decorated salt dishes by Charles Le Roux that are believed to have belonged to Peter Jay and Mary Van Cortlandt who were married in 1728; the three-piece tea set by Peter de Riemer, with the Van Rensselaer crest and initials of Philip Schuyler Van Rensselaer for whom it was made; the graceful yet restrained cream pitcher by Elias Pelletreau, in which the inverted pear shape persists, but with circular base; the classic urn-shaped sugar bowl with cover by John Germon of Philadelphia; and the fine, two-handled presentation bowl by Bartholomew Le Roux, now in the Garvan Collection at Yale University.

One cannot say with any certainty that these Huguenot silversmiths originated any design, but they were excellent workmen and most adaptable. They seem not only to have worked faithfully in the styles of the various countries in which they took refuge, but to have been quick to learn new forms. For instance, the only drinking vessel current in France at the time of the Huguenot exodus was the cup or beaker without handle. Yet the number of tankards, canns, and mugs, bearing the touch-marks of Huguenot smiths who settled in America, is impressive.

Creamer by Elias Pelletreau: Here, the 18th-Century inverted pear shape was modified. A circular base replaced legs, but the early influence persists. Pelletreau, an apprentice of Soumain, worked at Southampton, Long Island, 1750-1810. His son and grandson were also silversmiths.

Both tankards and mugs were made extensively in Holland and England where the refugee Frenchmen were quick to learn to make them. Consequently, tankards and related pieces were among the important forms which they made in America. They even followed the style trends of the particular locality where they settled, with the result that when members of the De Nys family moved from New York to Philadelphia the tankards they made there followed the New York tradition strongly.

There is one form which we always think of as typically American which I believe is of French descent. That is the deep basin-shaped dish with an earlike handle, known as a porringer. It is quite unlike the dish of the same name which was made in England late in the 17th and 18th Centuries. English porringers were practically the same as the two-handled caudle cups produced by American craftsmen.

Sugar Bowl by Germon: This urn-shaped piece shows the Adam influence as manifested in America. John Germon worked in Philadelphia 1782-1825.

The origin and use of the American porringer, which was made in both silver and pewter for nearly a century and a half, has always been a mystery. The following theory seems tenable. As early as the middle of the 17th Century, a piece of silver with two handles called an ecuelle was made in France. Quite often it had a cover and early examples had handles similar to the American porringer ears. It was used for soup or other individual portions of food. I believe that there is a direct relationship in design between the French ecuelle and the American porringer.

Therefore, it is probable that the porringer, as we know it, traveled to America by way of the French craftsmen who migrated into the Low Countries. Possibly, it was first made here by silversmiths of Holland training or ancestry.

Paul Revere II as a Classicist: These urn-shaped pieces, decorated with bright-cut engraving, show Revere working under the spell of the Brothers Adam. They are, undoubtedly, post-Revolutionary work done when he had returned to his craft after varied patriotic services.

At any rate, it was popular enough in America so that it was made by practically all of our silversmiths. I doubt if porridge was served in it; nor do I believe that the term bleeding bowl, applied by some English writers, reflects its original use. We have many instances of fine porringers being given as wedding presents, appropriately engraved with the initials of the bride and groom. Wedding presents are not apt to lean heavily either to the prosaic or the medicinal. It seems more likely that such a well-wrought, handsomely engraved silver dish would lend itself to sweetmeats or relishes.

Shortly after the middle of the 18th Century, American silver began to take on distinct rococo characteristics, but the inspiration came from England, not France. American Huguenots might still speak French in their family life, but their direct connection with their mother country had been severed.

Two-Handled Bowl by Bartholomew Le Roux: The maker was the first of his family to work in New York, where he was active 1689-1713. In shape, form of handles, and repousse decoration, this piece bears a distinctly Dutch flavor. It is very close to similar bowls by Jacob Boelen and Simeon Soumain.Two-Handled Bowl by Soumain: Simeon Soumain worked in New York circa 1705-1750. In design, this bowl shows the Dutch influence strongly. Its original owners were Hendrick and Catalina Remsen, married about 1730.

In England, on the contrary, Huguenot craftsmen gave definite impetus to the trend toward the rococo style which was in full flower there between 1720 and 1760. Being originally from the provinces, however, and of a Puritanic turn of mind, they tended to interpret it in a more restrained manner, which suited the English and their colonists across the Atlantic admirably.

Then, with the years, the rococo vogue passed and the classic designs of the Brothers Adam influenced silver as well as architecture. Again the adaptable Huguenots worked in this manner, fine examples being the John Germon sugar bowl, already mentioned, now in the Garvan Collection at Yale, and the fluted urnshaped sugar bowl and cream pitcher by Paul Revere II.

The chaste Adam style with its classic background very well fitted the temper of the times and appealed to a young nation acutely conscious of its republicanism. The artistic influence of a much earlier republic now expressed itself in architecture, furniture, silver, and other things used by man. Some of Paul Revere’s finest work was done in this style.

In addition to the sugar bowl and cream pitcher illustrated, three examples of his work during this period may be seen at the current exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Yale University. They are a tea set made in 1799 and loaned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; a tray made in 1795 and bearing the initials in script in an engraved oval, E D, which were for Elias Derby, Salem merchant prince; and an urn; dated 1800, loaned by the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Salt Dish in the Rococo Style: One of a pair made about 1740 by Charles Le Roux, son of Bartholomew Le Roux. It is among the most elaborately decorated pieces of silver of this style made in New York. Their maker worked circa 1724-1745.

Not so well known but nowise lacking in craftsmanship was his contemporary Abraham Du Bois, who worked in Philadelphia from 1777 on and also made silver in the classic manner as evidenced by the tea set shown on the cover of this issue. Also of this period was Elias Pelletreau most of whose long life was spent on Long Island.

The turn of the 19th Century found a number of silversmiths of known Huguenot ancestry working in America, but most of them had become so completely assimilated that they were far more American than French. Further, by the last decade of the 18th Century, another French migration had begun-but that is another story, and not to be confused with that of the Huguenot silversmiths.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

The Silver of Captain Tobias Lear of Portsmouth

The Silver of Captain Tobias Lear of Portsmouth Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I HAVE ALWAYS LOVED SILVER AS APPOSED TO GOLD. LITTLE DID I KNOW, UNTIL I DID SOME GENEOLOGY RESEARCH ON MY MOTHERS FAMILY. BUT, SOME OF HER GREAT GRANDFATHERS,GREATGRANMOTHERS AND THEIR SIMBLINGS WERE IN THE BUSINESS OF SILVER. THEY CAME FROM BRUHL GERMANY AROUND EARLY 1700’S. WHEN EDWARD CORNWALLIS CAME TO CANADA, NOVA SCOTIA. EVENTUALLY, THE UNITED STATES AND NEW YORK CITY. THE FAMILY NAME WAS DEBRUHL OR BRUHL. THERE ARE SUPPOSEDLY PIECES DONE BY SAMUEL DEBRUHL OR HIS SONS IN TNE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK CITY. THERE IS ALSO, A CHURCH THAT USES A SILVER TEA SERVICE IN THEIR BAPTISMALS AND OTHER OCCASIONS. MY ANCESTORS WERE PART ROYAL ARMY THAT PROTECTED THE QUEEN OF ENGLAND. ONE OF THEM MARRIED, EDWARD CORNWALLIS’S NIECES. I HAVE TRIED TO FIND ANY INFORMATION ABOUT THIS JUST FOR THE INFORMATION. BUT, I HAVE ENJOYED LEARNING INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT SILVER THAT I NEVER EVER IMAGINED. THANKS!THANKS! YOU HAVE MADE MY EVENING. I DO NOT HAVE A COMPUTER MY SELF. THIS IS ONE AT WORK. HARRAH’S CHEROKEE NORTH CAROLINA.

THE FAMILY EVENTUALLY MADE THEIR HOME IN SOUTH CAROLINA,CAMDEN AND GEORGETOWN. TWO OF THE SONS CAME TO THE MOUNTAINS, DURING CIVIL WAR. THOSE SONS WERE THE BEGINNING OF MY MOTHERS DEBRUHL FAMILY, HERE IN THE MOUNTAINS OF WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA.

Betty,

So glad to see you are posting. Hope to see you next year at the Reunion in Mars Hill. Stay well and update your story as facts become more revealing. I have a blod site just go to Google and type in normandebruhl

and select the first or second link that comes up. See Ya. Norman.

i have e sugar and creamer from my aunt and it is marked on bottom

revere silversmith inc with a shield and it says sterling reinforced with cement and a number 1306 can you tell me how old it is.it has a decoration of fruit around the outside rim.

thank you

Excellent article ! I had recently purchased a coffeepot marked “Revere”. … It is supposed to be attributed to either Paul Sr. or Paul Jr. … It is very similar in style to the domed tankard pictured in your article. … I had just stumbled across your Collectors Weekly site quite by accident while searching for information on early American silver. … I am not a silver collector, but am attracted to most 18th century styles. My house is also more than 300 years old. … I have always firmly believed that the style of many 18th century items can never be improved upon, and silver pieces are included in that belief. … You can be sure that I’ll be back to your site again and again. … Thank you for reprinting this very well written article in an electronic format so that people like myself can read it for the first time.

i was trying to find out about a silversmith named T.Cox Savory from england i have a tea set and no very little about it are him

I have a silver spoon; engraved within the bowl, half mother of pearl (?) shaft and a smooth round ball finial. On the reverse shaft just distal to the bowl and on the long axis are the block letters J E & S S. Just distal to these and on a transverse axis to them are a block letter pair, EP. The letters are well struck and clear. Any ideas?

I have a silver plated mug with very intricate tooling of birds and what appers to be grapes on the sides, and a pattered band around the bottom, that was handed down to me by my grandmother who claimed it had been buried by her family during the War Between The States–it has a large blob of metal right on the side of the makers mark, and all I can make out are the letters “Silver Pla—and two letters prior to those that say “OX” I know it probably isn’t worth anything to anyone but me, but I would be delighted to know its origin and maker. I have always thought it was so unique due to the time it would have taken the silversmith to do all those little dots that make up the pictures of the birds and grapes. If anyone could shed some light on this, I would be most appreciative. Thank you!

I am the gggranddaughter of Adolphe Himmel, NOLA silversmith. I have been trying to research his life & family. He was supposed to have been born abt 1825 in Germany, immigrated to the US abt 1845, married a French woman and raised his family in NOLA & died there. Do you have any ideas where he could have done his apprenticeship? How young & how long would that have taken? Is there a place where apprentices would have been registered? Also would he have possible apprenticed in Germany, France or the US? I have not been able to track his early life and would very much like to find out more about him. Thanks for any help. Fran Stiles

My Great grandfather Josiah Poyton came to Ameica and workd at Tffany’s in new York and Gorham Company in Providence, RI. Born in Bethnal Green, England.

What can you give me to fill in the blanks Father and mothers names.

Robert F. Poyton

Just purchased an Andrew Demilt coin silver spoon -9 inches. Was he of Huguenot origins?

Do you know where the two-handled bowl by Simeon Soumain is located?

Thank you.

My 5th great grandfather, Daniel DeShon, from New London, Connecticut and originally from France was a silversmith. He used “DD” on his work. Where could I see some of his silver?

I have a couple of pieces from my parents’ home. One is a silver serving bowl with a matching lid. It says International Silver Co. on the bottom. Is it worth anything? The other piece is a small saucer/dish like piece that says Wm. Rogers on the bottom. Is that worth anything? The 3rd piece is a small saucer with the letters: K, A, C, C engraved on it. It says Reed and Barton on the back with the numbers and letter: 4 3 9 4 S. Does it mean anything and is there a value to it? Thank you for your help, Judi

We have a very large silver serving “ladle” (? ) which has a long handle and flat circular “bowl” ( I don’t know if it is a ladle ..) It is ornately decorated – looks like the image on it was hammered in – and is of a scene of several (5) important looking men sitting on a wharf or terrace at a port with a beautiful clippership in the background and a fishing net which fills in the rest of the area. There is an inscription on it saying: “Peter de Groot 1697 Le….. ( I can’t read it ) and the equally ornate handle has two images – one over the other – of a fisherman, one with a net, and one casting a line.The rest of the decorations which fill up the piece seem to be flowers and leaves. Nothing on the back except hammered silver on the ladle and plain silver on the handle.

Thank you for any thoughts you might have, Wendy Sloan