It’s Valentine’s Day, so naturally our thoughts turn to divorce. That’s the odds-even outcome of marriage, if you believe the oft-cited statistic that half of all nuptials in the United States will end up on the rocks. In fact, the overall rate is more like 30 percent, and the frequency of divorce has been dropping since the 1970s, when 37 states amended or repealed their divorce laws, causing only a short-term spike in the practice.

“Nevada’s adjacency to California made the state especially convenient to the promiscuous citizens of the burgeoning movie colony of Hollywood.”

Today, getting an uncontested, no-fault divorce is easily accomplished in all 50 states. That’s very different from the way things were during most of the 20th century, when divorce was officially frowned upon, suppressed by onerous state laws that actively discouraged the civil disunion of couples ready to be singles again. For example, until 1985, the only way to get a divorce in the state of New York was to prove your spouse had committed adultery, which wasn’t much help to women in abusive relationships.

In the 1930s, though, the city of Reno, Nevada, shined like a beacon of hope to the unhappily married. Reno was the nation’s divorce capital, with many of its finest hotels strategically located near the Washoe County Courthouse, where judges granted divorces with assembly-line efficiency. Outside the city limits, to the south in the Washoe Valley and to the north near Pyramid Lake, guest ranches also catered to the men and women (though it was mostly women) who would move to Nevada for six weeks to establish residency. It didn’t really matter why a husband or wife wanted a divorce (grounds for ending marriage were interpreted extremely liberally), only that the plaintiff had been a resident of the great state of Nevada for a full six weeks. This, and only this, would get them out of their till-death-do-us-part vows.

Above: Women crowd the bar at the Pyramid Lake Guest Ranch north of Reno. Top: A postcard from the 1940s depicts the practice of tossing one’s wedding ring into the Truckee River from the Virginia Street Bridge after being granted a divorce. Both photos courtesy Special Collections, University of Nevada-Reno Library.

Accompanied by a witness to confirm her residency, the plaintiff and her lawyer would stand before a judge, usually for no more than a few minutes, to briefly plead her case. This was briskly followed by the judge’s rubber-stamp divorce decree. For many, the next stop was a train or bus out of town, even though the plaintiff had just sworn, under oath, that she intended to make Nevada her permanent home. It was, as historian Mella Rothwell Harmon calls it, “institutionalized perjury.”

According to Harmon, who has documented the impact of Nevada’s divorce laws on Reno in the 1930s, the statutes making the state a haven for divorce go back to Nevada’s territory days, before it was granted statehood in 1864. As a territory, Nevada’s residency requirement was short (six months) compared to the durations required in actual states (usually a full year). Six months was apparently a long time for most people in the mid-19th century to spend in Nevada, where the boom-bust cycles of silver and gold mining produced seesaw fluctuations in the state’s population. Thus, a short residency requirement was just about the only way to muster enough legal residents to vote in local elections. Since the right to receive a divorce decree was also tied to residency, Nevada’s divorce laws were perceived as being lenient, even though they had not been written to undermine the sanctity of marriage, let alone poke a finger in the eye of “American family values.”

Reno’s Riverside Hotel was built in 1927 next door to the Washoe County Courthouse to accommodate divorce-seekers lured to the state by its then three-month residency requirement. In 1931, the state’s residency requirement was shortened to six weeks.

Interestingly, making Nevada a state was not all it seemed, either. Rather than a heartfelt, patriotic recognition of Nevada’s contribution to the Union, statehood was actually a means to an end for President Abraham Lincoln, who needed Nevada’s new electoral votes to secure his re-election. As an important side benefit, statehood kept the territory’s silver out of the hands of the Confederacy and helped fund the final year of the Civil War.

“The tawdry plot went something like this: Wealthy, sex-starved socialite from back east has torrid affair with randy, ruggedly handsome ranch hand.”

After Nevada became a state, its residency requirement was set at six months, which, for a while, was the shortest in the land. By the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a few unhappily married non-Nevadans had realized that six months in the Silver State could free them from a hurtful, loveless, or just-plain-boring marriage in half the time it would take in most other places. One of the most famous divorces of this early period occurred in 1906, when Laura Cook Corey, then the wife of United States Steel president, William Ellis Corey, settled in Reno for six months for the sole purpose of getting a divorce decree from her wealthy husband. The uncontested grounds were desertion, and her $3-million settlement, which included custody of the couple’s son, was a tabloid sensation.

Nevada’s adjacency to California made the state especially convenient to the promiscuous citizens of the burgeoning movie colony of Hollywood. In 1920, for example, Mary Pickford relocated to Minden, just south of Reno, for six months to end her marriage to an Irish actor named Owen Moore so she could wed the dashing Douglas Fairbanks. By the end of the 1920s, the “Biggest Little City in the World,” as Reno had taken to calling itself, had made the practice of divorce downright fashionable.

In the first half of the 20th century, a popular euphemism for divorce was the “Reno cure.” Photo courtesy Special Collections, University of Nevada-Reno Library.

Before long, other jurisdictions decided they wanted a piece of the action Reno was earning from its well-heeled short-timers, who lived, wined, and dined as if, well, they were about to start a new life. In 1927, when Mexico and France were reportedly considering lowering their residency-for-divorce requirements (even though many states did not recognize foreign divorce decrees), Nevada preemptively countered by lowering its requirement to three months. This spurred Idaho and Arkansas to do the same, to which Nevada responded again, in 1931, by lowering its residency requirement to just six weeks.

By May of 1931, there were so many divorce seekers flooding into Reno, some were forced to camp on the banks of the Truckee River for the lack of accommodations in town. Gambling had been legalized that March, which lured even more people, and in 1933 the state won the amoral trifecta, as it were, when Prohibition was repealed. All told, during the 1930s, more than 30,000 people came to Reno to get a divorce, pumping an estimated $5 million per year at its height into an economy whose population hovered around 20,000 full-time residents throughout the decade.

An unidentified divorcee hides her face from a prying photographer’s lens at the Washoe County Courthouse. Photo courtesy Special Collections, University of Nevada-Reno Library.

Not all of those who came to Reno for a divorce were able to fork over its $1,500 average cost without working during their residency. Many of the women who came to Reno to get unhitched found jobs, even during the Depression, as waitresses, nurses, housekeepers, and ranch helpers, a testament to the booming economy caused in no small part by their very presence.

Unsurprisingly, though, the national media preferred to spend its resources reporting on the pending divorces of the rich and famous, such as Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, who arrived in Reno on March 30, 1935, to extricate herself from her ill-advised marriage to a Georgian playboy prince named Alexis Mdivani. The Hutton case put an estimated $15,000 to $20,000 in the pocket of Reno attorney George Thatcher (with an estimated net worth of $50 million, Hutton could easily afford it), who vacated his home so his marquee client could satisfy her residency requirement in comfort and privacy.

George Cukor’s “The Women” from 1939 was based on screenwriter Clare Boothe Luce’s own Reno divorce in 1929.

Even better were storylines with lots of sex and scandal. In pulp novels, the phrase “Reno cure,” as getting a divorce was then known, became code for “getting some action.” The tawdry plot went something like this: Wealthy, sex-starved socialite from back east has torrid affair with randy, ruggedly handsome ranch hand, who is only too willing to help his female guest shake the memory of her almost-former husband. According to writer Patricia Cooper-Smith, novels with names like “Divorce Trap,” “Whirlpool of Reno,” and “Reno Rendezvous” played up this and other sensational scenarios of getting a “Renovation,” which was gossip columnist Walter Winchell’s word for a Reno divorce.

In fact, the fictions spun about Reno divorces were based in part, at least, on a few key kernels of truth. One ranch, the Lazy ME just south of town, was known by locals as the “Lay Me Easy,” a reputation helped along, unwittingly or not, by the Lazy ME’s practice of sending a car driven by a good-looking, young male driver to the nearby train station to meet its female guests. Other ranches, though, had more wholesome reputations: Pyramid Lake Ranch, for example, was known as a place where would-be divorcees could bring their children.

Pulp novels of the 1930s and ’40s sensationalized the lurid side of getting a divorce in Reno.

The image of women whiling away the weeks on a Nevada dude ranch was codified in 1939, when the screen version of Clare Boothe Luce’s 1936 play, “The Women,” debuted. Based on the New York writer’s own Reno divorce in 1929, the George Cukor-directed film starred Joan Crawford, Joan Fontaine, Rosalind Russell, Norma Shearer, and Paulette Goddard, but not one male actor, although off-camera men were portrayed as the source of most of the women’s problems.

Another Reno divorce story with both true and apocryphal roots concerns the “tradition” of newly divorced women exiting the Washoe County Courthouse, walking to the nearby Virginia Street Bridge, the so-called “Bridge of Sighs,” and tossing their wedding rings into the Truckee River below. The roots of this legend appear to be a 1929 novel titled “Reno,” which describes this ritual. According to an article in Nevada Magazine by Holly Walton-Buchanan, Renoites always doubted the story, a skepticism that seemed confirmed in 1950 when a cleanup of the river below the bridge only turned up one ring. But in 1976, three coin prospectors with a dredge found 90 rings, and over the next three summers they found 400 more.

John Huston’s “The Misfits,” 1961, is set on a Reno divorce ranch. It was the last film for both Clark Gable, who got his own Nevada divorce in Las Vegas, and Marilyn Monroe, whose marriage to the film’s screenwriter, Arthur Miller, was on the rocks during filming.

By the end of the 1930s, Reno’s claim as the Divorce Capital of the World was threatened by the rise of newly electrified Las Vegas, one of the first customers to purchase power from recently completed Hoover Dam. Vegas was a lot closer to Hollywood with than Reno, which drew the likes of Ria Langham (who was divorcing Clark Gable) to town in 1939. After that, Las Vegas became the place to untie the knot.

Curiously, Gable would go on to star in “The Misfits,” his last film, released in 1961 after his death in 1960. Written by playwright Arthur Miller and starring Miller’s then-wife, Marilyn Monroe, “The Misfits” told the story of the relationship between a young divorcee (Monroe) and an old cowboy (Gable). Even though Las Vegas was becoming more prominent in the popular imagination of the early 1960s, nostalgia for a golden age of divorce, if you will, dictated the film’s setting—Reno, Nevada.

(Thanks to Special Collections, University of Nevada-Reno Library.)

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Love Boats: The Delightfully Sinful History of Canoes

Love Boats: The Delightfully Sinful History of Canoes Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

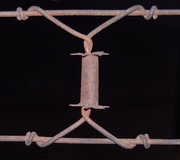

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You Barbed Wire, From Cowboy Scourge to Prized Relic of the Old West

Barbed Wire, From Cowboy Scourge to Prized Relic of the Old West Engagement RingsSince Roman times, men have been giving engagement rings to their blushing …

Engagement RingsSince Roman times, men have been giving engagement rings to their blushing … Valentines Day PostcardsToday, antique and vintage Valentine postcards from the Victorian and Edwar…

Valentines Day PostcardsToday, antique and vintage Valentine postcards from the Victorian and Edwar… Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted…

Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Did I miss something? If all you needed was residency in a state why not just get divorced in the state where you were? What made Nevada a better choice than others? I see the blip about NY requiring adultery but there were 47 other states at the time (pretty sure)!

Coincidentally I just watched “Charlie Chan Goes to Reno,” and the fact that Reno was sort of a Divorce Resort was a prominent part of the plot. I never knew that part of Reno’s history. I guess divorce must’ve been a difficult thing in the past. The Mexican quickie divorce was another recurring joke in the ’50s.

Monkey –

“Today, getting an uncontested, no-fault divorce is easily accomplished in all 50 states. That’s very different from the way things were during most of the 20th century, when divorce was officially frowned upon, suppressed by onerous state laws that actively discouraged the civil disunion of couples ready to be singles again. For example, until 1985, the only way to get a divorce in the state of New York was to prove your spouse had committed adultery, which wasn’t much help to women in abusive relationships.”

Read for comprehension.