Like the soldiers who fought in World War II, most of the men and women who served in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War in the ’60s and ’70s were remarkably young, between the ages of 18 and 25. Those who volunteered to man the primary aircraft of the war, the helicopter, put their lives at a risk every day they were on tour. As a result, their commanding officers were often willing to look the other way when the pilots, gunners, and other crew members had their helmets painted in bright colors with their girlfriend’s name; their call sign or unit insignia; their favorite rock bands or comic-book characters; or mascots from their hometowns, in much the same way World War II pilots painted their leather A-2 flight jackets.

“They were painting the peace symbol on their helmets, and then taking off and shooting at people every day.”

Perhaps most interesting are the helmets painted with ironic or dead-serious anti-war messages, as well as the prevalence of stars-and-stripes helmets, which at first glance may seem like obvious patriotic riffs on the flag and the popular Nazi-smashing comic superhero Captain America. But there was another rebellious “Captain America” known for his stars-and-stripes helmet that young men idolized in 1969—the motorcycle-riding hippie played by Peter Fonda in the film “Easy Rider,” who imports illicit drugs from Mexico, mingles at a commune, patronizes a brothel, and freaks out on acid.

We talked to John Conway, a military aviation collector who runs The Legacy of Valor website for the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association Museum, a Collectors Weekly Hall of Fame site. Conway graduated from high school just after the fall of Saigon in 1975, which brought the war to an end. Because of that, he never enlisted, but he’s always admired the bravery of the men and women who served in times of war. For years, Conway’s been collecting these helmets and, more importantly to him, the stories of the servicemen who wore them.

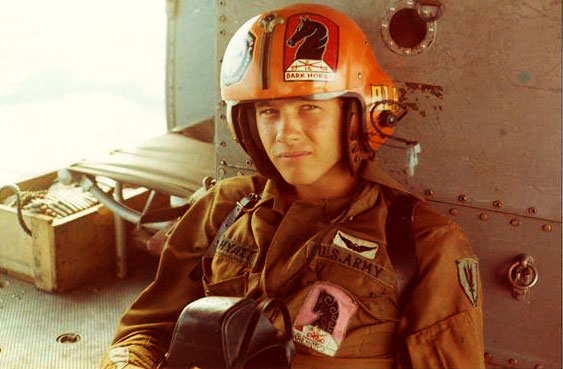

Top: Lift platoon Crew Chief John Hyatt sports a bright orange helmet with platoon and troop patch designs. (Courtesy of Hyatt, via VHPAMuseum.org) Above: An unusual early U.S. Air Force helmet used by an Army rotary-wing aviator, restored by Don Mong. (Via VHPAMuseum.org)

Collectors Weekly: What was the role of helicopters in the Vietnam War?

Conway: Prior to the Vietnam War, military use of the helicopter was somewhat limited. Vietnam was the first time the Army really explored its air mobility. The helicopter allowed them to put a certain number of troops on the ground in a specific area for a specific action for maybe a very short time. The Air Force had been a part of the Army until ’47, when the Air Force became a separate branch. So at that point, the Army backed away from aviation on a large scale. But the Vietnam War made it necessary for the Army to bring it back. And the helicopter proved to be the perfect vehicle.

“When the pilots left that Army ‘family,’ they came back to a world that had no idea what they’d accomplished.”

In the war, the Army used helicopters for medical evacuation, for troop and supply transport, and for scout patrol—checking out the area without putting people on the ground—and then ultimately as a weapons platform they called “gunships.” They were largely used for air-to-ground support. Other helicopters were used as reconnaissance forces; then there were the lift platoons that took the soldiers in and brought them out of the combat zone; and then the gun platoons that supported their efforts. If the gun platoon couldn’t secure the fight from the air, then troops were inserted on the ground.

Helicopters were also used for courier missions. Due to the nature of the situation in Vietnam, you couldn’t just jump in a Jeep and drive from place to place because so much of the area between point A and point B was not under control. The enemy set up ambushes on the roads, and flying over them was the best way to defeat them. The helicopters were also used for artillery observation, or as “command-and-control ships,” which would take the unit commander up where he could watch the situation and call the shots from the air.

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Lowell L. Eneix recalls, “They had presented me with a freshly painted helmet. It was the most perfect titty pink color, they had mixed and experimented for about a week to get that color. They were proud and so was I.” (Courtesy of Eneix, via museum.vhpa.org)

As the Army started to develop their helicopters, the different models were named after Native American tribes, like Iroquois, Kiowa, Cayuse, and Sioux. The Iroquois is more commonly known as the Huey, a nickname that came from its designation, UH-1. Hueys were the universal aircraft of the Vietnam War and were flown by U.S. Navy, Air Force, Army, and to a limited degree, the Marines. They first served in the role of couriers and troop transport. But they were soon adapted as gunships early on as the Army developed armament systems that utilized 20mm cannons, grenade launchers, 50-caliber machine guns, and then rocket systems. Hueys served in the gunship role for a number of years.

The Bell OH-13, the Sioux, was like the helicopter you see on “M*A*S*H,” and they called it the flying Erector Set. It was good for low-level observation but not terribly fast and pretty vulnerable to ground fire. The AH-1 Cobra was among the first military helicopters to break out of the tribe-name mold. It was a fast ship. Because it was smaller and lighter, it was also able to carry bigger armament loads. The speed and increased fire power of the Cobra was a big turning point for gunships. And the Army had heavier helicopters, like CH-54 Tarhe and CH-47 Chinook, for moving troops and equipment. To a limited degree, some of those aircraft had combat involvement and still do, even though they were basically designed to be flying trucks.

Wayne Moose, a scout gunner for F Troop 4th Cav Air, says “I wrote home to my parents for paints and brushes so I could paint my helmet.” (Courtesy of Moose, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: What were the helmets like?

Conway: The early helmets were basic in terms of protecting your head and your hearing. At first, the Army just wanted lightweight headgear that protected your head from normal, everyday bumping and thumping inside the confines of a closed space, and housed communication equipment so it could be utilized hands-free. Then, helmets were developed with interior suspension systems instead of a just little bit of foam rubber between you and the outside of the helmet, so the shock of an impact could be more absorbed by the suspension system and not so much by the head and neck.

“For American soldiers, the word ‘uniform’ is a misnomer. They’ve always tried to have some little thing that set them out apart from the others.”

Also, as the war went on, it was discovered that aviators were developing hearing problems because of the incredible noise they were exposed to. In most of the aircraft, the pilots and the crew were in very close proximity to the motor and transmission, which were a constant source of noise, not to mention the sound of the weapons systems when they functioned. The military equipment laboratories later made improvements to make the earpieces fit closer so there was less ambient noise coming in. That helped with the clarity of communications, and it was also designed to preserve hearing.

Eye protection didn’t change too much. Some Navy and the Air Force helmets had dual visors, which were usually clear and tinted—used singularly or together for various conditions. The Army had single-visor helmets that could be worn in conjunction with or instead of sunglasses. Years later, the Army shifted to a dual-visor helmet. There wasn’t a great deal of variety in Army flight helmets during the Vietnam War, but you do occasionally see Army guys using dual-visor helmets they had acquired from the Navy or the Air Force through wheeling and dealing. Most anyone would want to try to get something that’s different from what everyone else was using. But that’s another story!

Army lift platoon Commander Judd Clemens “commandeered” this U.S. Air Force flight helmet and had it painted with a quote from Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, “Do not take counsel of your fears.” (Courtesy of Clemens, via museum.vhpa.org)

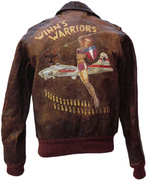

Collectors Weekly: Why did the servicemen paint helmets instead of jackets?

Conway: Most of the air space, even up north, was warm because of the tropical climate, so the pilots didn’t wear heavy leather jackets. Instead, they wore lightweight clothing that had to be laundered frequently. Because of that, there wasn’t the same degree of personalization on their clothing as there was on their helmets, which were, with their smooth texture, very easy to paint. They did wear unit patches on their flight clothing, but they weren’t personalized to the same extent as the World War II flight jackets. The painted helmets would have nicknames, timely symbols, and cartoon characters, things that were more of a personal nature than the unit patches.

Collectors Weekly: What were the official Army rules about personalizing helmets?

Conway: It was not authorized, but enforcement tended to vary from unit to unit. Some commanding officers had no problem with artwork on helmets or aircraft, and some of them strongly discouraged it. There was no real pattern to it. A given unit might be flying daily with all the artwork they could muster, but when their commander reached the end of his tour and left country, the new guy could come in and put the wraps on all of it. There really wasn’t a strong Army doctrine that was universally enforced. Largely, it was tolerated. When you’ve got a guy who’s looking death in the eye every day he jumps in a helicopter and takes off for combat, it’s hard on morale to come along and tell him he can’t paint his girlfriend’s name on his “bird” or his helmet.

Pin-up imagery was rare on Vietnam helicopter helmets, but this “enhanced” image of a crew chief’s wife was also painted on the assault helicopter itself. (Courtesy of John Leandro, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: In what ways did these helmets help boost their morale?

Conway: It was a form of self-expression in a fairly uniform environment. As I’ve always said, the word “uniform” is a misnomer for American soldiers. Since the days of the Revolution, they’ve tried to have some little thing that set them out apart from the others, something that made them who they were, whether that was a certain kind of a badge or button, or some kind of an emblem carved in the stock of their weapons. Feeling good about yourself is an important part of morale in any team, and self-recognition and individuality are a big part of that.

Collectors Weekly: Did personalized helmets put the servicemen at risk in any way?

Conway: It didn’t really matter too much. When the Army first went to Vietnam, the helmets were white, which the crews perceived as making their heads perfect targets. At some point, the orders came down for the personal equipment people to take the helmets in and paint them Army green. You do find some of the early helmets that actually started out being white and got painted green. In terms of the personalization, I’ve seen some really crazy stuff. Some servicemen painted their helmets bright orange or pink, to show they were tempting fate. But hitting a guy in the head from the ground with an AK-47 when he’s in a moving helicopter is more a matter of luck than it is skill. So a bright helmet was probably fairly inconsequential as a tactical problem.

Command aviation company Crew Chief Jim Lorenzo put his heritage on his helmet. It says “2nd Flt Plt” on the left and “gunship crew chief” on the right. (Courtesy of Jim Lorenzo, via John Jones, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: How did the experiences of helicopter pilots in Vietnam compare to those of the Army pilots in World War II?

Conway: When it comes to Americans, we all like a fight when we think it’s right. I think the spirit of patriotism and the will to help oppressed people was there in Vietnam just like it was in World War II. You still had the youthful effervescence of young men who were intelligent, well-educated, and flying a very expensive aircraft. Not only was the aircraft at stake, but also your passengers, so there was a huge sense of responsibility in both wars.

On the other hand, most of the Vietnam guys were raised by the World War II generation and never lived through the poverty of the Depression. Not so many of them were raised on farms. Instead, you had kids that were raised in the city. You had the integration of people of all races and backgrounds in the aviation crews, which didn’t occur so much in World War II.

Army fourth-class Specialist John A. Hubert, a.k.a. Harpo, painted this ballistic helmet with a University of Kansas Jayhawk holding a John Wayne-style six gun for George McClintock. (Courtesy of McClintock, via museum.vhpa.org)

Of course, the big difference is the Vietnam guys came back from a war where we weren’t the clear and obvious winners. So they dealt with the social implications, and it was quite a trauma for a lot of them. As a part of a cohesive team in their unit, they all depended on each other. When they left that “family,” they came back to a world that had no idea what they had accomplished and lived through. They were sometimes perceived as baby killers or drug freaks, completely erroneous perceptions that had been generated by the media and also by protesters and the subculture.

“When you’ve got a guy looking death in the eye every day, it’s hard on morale to tell him he can’t paint his girlfriend’s name on his helmet.”

In general, with the helicopter pilots and their crews, you didn’t find the prevalence of drugs. You didn’t find people going AWOL because they had actually volunteered to do what they were doing. The Army didn’t draft people to become helicopter pilots or door gunners because of the risk. Going into aviation, that was a choice.

One day, I called a veteran who had shared some stuff with me, and his wife answered and she said, “When John came back from Vietnam, people threw feces at him at the airport. You know, he saved lives over there. He did the best job he could possibly do, and he lost a big part of his life, only to come back and be greeted like that.” And she said, “You don’t how important it was for him to find somebody like you who understood, appreciated, and cared.”

Team Commander Doug Kibbey says, “The little brother of a stateside girlfriend sent me this, and having seen every imaginable permutations of ‘badass’ helmet designs, I decided this was perversely sinister enough for my oblique sense of humor. Besides, I felt better about the laughter of others when they looked at me.” (Courtesy of Kibbey, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: What kind of images you would see on these helmets?

Conway: It didn’t stray too much from the sort of things you saw on World War II flight jackets. They would pick designs that reflected their aircraft, unit insignia, or radio-identification names known as call signs. A lot of times, the unit insignia would correlate with the call sign. For example, people in Troop C, 16th Cavalry, their image was a black knight from a chess set, and they called themselves Darkhorse. The call signs for that unit, they would start with Darkhorse 1 and go upward to reflect the platoon an individual was assigned to.

You also see designs that reflected the state or city the serviceman was from. On the Legacy of Valor site, there’s one with the University of Kansas Jayhawk mascot painted on the back. The guy’s name is McClintock, so the Jayhawk is holding a six gun, which references the John Wayne movie, “McClintock.” You often see a woman’s name on a pilot’s helmet, usually his wife or girlfriend. And you see all sorts of other influences. I’ve seen designs based on Greek mythology, comic-book characters, as well as ironic or motivational statements, like the one on the site that quotes Stonewall Jackson, “Do not take counsel of your fears.”

In addition to having a condor painted on the back of his helmet, Rick Schwab tied a piece of a strap from his fiancée’s bikini to his microphone for good luck. (Courtesy of Schwab, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: There seem to be fewer lucky charms than on WWII flight jackets.

Conway: That’s true. You don’t see four-leaf clovers, rabbit’s feet, or anything like that too much. It wasn’t so common anymore. Again, I would attribute that to guys being raised in a much less earthy background. These guys were often college-educated and raised in the city, where both parents probably worked. It was just different times. One man represented on the site, Rick Schwab, met his fiancée when he was in Hawaii for R&R. She trimmed down the strap on her bikini because it was too long, and he took that piece she cut off and tied it to the microphone of his helmet. You did see things like that, but they were not so much based on superstition. You didn’t see a lot of pin-up art either. For some reason, that wasn’t really prevalent on helmets. Maybe it was anticipated that they would be taken home as souvenirs and a racy image might be hard to explain to a daughter or granddaughter years later?

Wayne Mutza says, “Although this is not the flight helmet I wore in Vietnam, which was painted black, it served as a log of things I’ve done.” This helmet also lists Pakistan, Cambodia, and Korea as places he did tours of duty in. (Courtesy of Mutza, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: I noticed some helmets had peace signs, marijuana symbols, or psychedelic lettering. Were some of these guys part of the ’60s youth culture before they left?

Conway: Yeah, some of them were. But the symbols didn’t always mean exactly what they looked like on the surface. In regards to the peace sign, in some cases, it was meant as social commentary on the irony of the situation they were in. They were painting the peace symbol on their helmets, and then taking off and shooting at people every day. The guy who owned the helmet with the peace sign on the site, he recently passed away. For the site, he wrote about his flying scarf. His unit gave scarves to everybody as a membership ritual, and they all had to have it embroidered with their name and their call sign. When he picked his up, he had the seamstress flip it over, and on the backside of it—and pardon my French because this is not language I use normally use—he had her embroider “Fuck this asshole war.” At some point in the game, he developed his own anti-war sentiment, but for whatever reason stayed with the job and got through it.

Like I always say, there are a lot of deep psychological implications to this war. It’s something that you don’t run into with World War II stuff because you had guys that were raised in simple environments and their job was clear-cut. The WWII vets had support back home, and when they returned, everybody loved them. The soldiers in Vietnam were getting news from home within hours, which the guys in World War II didn’t get, and it wasn’t always favorable.

Doug Callison traded for this dual-visor helmet with an Air Force friend, who also got it painted camouflage colors for him. The painter, “couldn’t wait to turn the helmet around to show me his handiwork on the backside. He had blended in a tan ‘Bird’ or ‘The Finger’ on the back. I was elated, to say the least! I could simply turn my head to let those next me know that they were #1 with me too.” (Courtesy of Callison, restored by Don Mong, via museum.vhpa.org)

I guess it all kind of depended on where you were at the time. If you were in school during the youth movement of the era, I think it was a major awakening of social conscience. The presence of politics and big business in the war was starting to become obvious. The South Vietnamese forces that we were supporting, in many instances, we far less committed to the situation than we were. So that sort of information was going back home.

Collectors Weekly: Were the stars-and-stripes helmets based on the flag or were they based on “Easy Rider”?

Conway: I think it was a little of both, really. The image of Peter Fonda on that motorcycle with the stars-and-stripes helmet and his low-key yet rebellious persona as Captain America captured a lot of people’s imagination. Also, the original Captain America, the comic-book superhero, was a childhood hero for a lot of those guys. On the site, you see Hugh Mills in a helmet that says boldly, “WAR” on the front of the visor. You can’t see it, but on the left side it says, “can be hazardous to your health.” And on the right side of his helmet, it’s painted with Captain America holding his shield. Mills was a guy who went over voluntarily. He was well-educated, he made a career out of the Army, and he was never involved with the drug culture. He relished the irony of the statement his helmet made. He is still active in his community as a law enforcement officer today.

Counterculture hero and biker “Captain America,” played by Peter Fonda in the 1969 film “Easy Rider,” at left, wore a very patriotic helmet—a style that was popular with men manning helicopters in Vietnam, like Bill Blackburn, at right. (Courtesy of Blackburn, via Joe Stone, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: Did the servicemen ever use these painted helmets to keep a tally of victories like the WWII pilots did on their jackets?

Conway: It’s not really all that common, but sometimes a helmet has a countdown for “DROS,” or the day the serviceman returned home from overseas, what was called a “short-timer’s calendar.” Usually, when a guy got down to the point where he only had somewhere between 30 and 60 days left, his commanders would pull him off flight duty so he would have less of a chance of getting terribly injured or killed within days of returning home. Some refused and flew right up to the last day of their tours.

I’ve seen a helmet that’s got tombstones painted on the back of it that symbolized how many confirmed kills the pilot had from his best recollection. Helicopter vets call that “KBA,” or “killed by air.” Again, you don’t often see anything that aggressive. The guy told me he didn’t wear the helmet much, but his unit had a tech rep—civilians that work for the companies that manufacture various sorts of equipment, weapon systems, or even the aircraft—and the rep was a fairly talented artist. I think he had him paint three helmets, and one of them had the tombstones on it. Those would be the only two things I know they kept track of by using their helmets as a “scoreboard” of sorts.

A rare example of a Vietnam helicopter helmet painted with a count, mostly like “KBAs,” or enemies confirmed “killed by air,” designated with the Viet Cong flag. (Courtesy of Steve “Tooth” Bookout, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: Did they also turn to the person in their unit who could paint?

Conway: Yeah, you run into a lot of that. Also, the Vietnamese were very enterprising, and I’ve heard that some of the really artistic stuff was done by Vietnamese street artists. I’ve also seen examples of parts from helicopters that had been smuggled into town for these artists to paint.

Collectors Weekly: How much are the helmets going for now?

Conway: As it turns out, the helmet art section of the website has helped generate a competitive situation for buying these things now. I used to frequently buy them off eBay and at shows, but now the price ranges are staggering, considering how much they’ve changed. In general, they run somewhere between $300 and $600. I saw one that was just a stripped-down shell with the stars and stripes painted on it. The visor housing was gone, and it was pretty torn up, but it still brought in 250 bucks. It seems like the primary, serious interest is from people overseas, in countries like Italy and France.

Doug Buchanan, who had a viper skin on his helmet, said, “While on the 707 flying across the pond, an Army Military Intelligence Captain sitting next to me asked me what unit the patch represented. I said it was a marijuana leaf. He sunk down in his seat and looked around. He was noticeably nervous the remainder of the long flight.” (Courtesy of Buchanan, via museum.vhpa.org)

Collectors Weekly: While collecting these helmets, what are some of the best stories you’ve heard?

Conway: Doug Buchanan, who recently passed away, killed a poisonous snake in Vietnam, and then he tanned the skin and glued it to his helmet. Larry, the man who had the helmet with the tombstones, he also had an all-black helmet with a cav insignia and his unit patches on it. His wife, Carol, was an evacuation nurse in Vietnam, stationed very close to where he was. Actually, when they went over there, they weren’t married. In fact, at the time they got sent overseas, they weren’t consistently dating. When they discovered how close they were to each other during the war, they said, “Let fate take over,” and wound up getting married in country.

Before they got married, Carol actually flew on a combat mission with Larry’s unit. She was put in one of the gunships supporting the scout mission Larry was on. The scouts flew down so low that it was very dangerous but the guns were up high, watching the situation in relative safety. Larry was actually shot down that day. Carol was in the gunship high above, watching it all happen, wearing his black helmet on the mission.

Mike Brockovich says, “All the original Toro pilots had the Toro hand painted on their helmets by warrant officer Lester A. Hansen, who ended up an MIA. My helmet was the only one modified with an Air Force visor and painted with horns.” (Courtesy of Brockovich, via museum.vhpa.org)

So there you have a helmet that was actually worn by a Vietnam vet and custom-painted for him, but it’s also a helmet worn by an evacuation nurse on a combat mission where her future husband was shot down. Larry was rescued, but Carol was very upset with the situation. I think before that point in time she may have never quite realized how dangerous his job really was.

Larry’s kind of a free spirit, a cowboy at heart, and Carol is a nurse. She’s focused, serious, and very methodical about things. Larry’s somewhat the opposite. They’re great people, and they have a wonderful family now. They spent several days with us this summer. The fact that we care about each other and are great friends is probably the only reason I have that helmet now. I don’t think Larry would’ve given it to anybody else.

Jim Kluender says, “Me with my helmet – didn’t even know that sneaky photographer took the photo until later!” (Courtesy of Kluender, via museum.vhpa.org)

(To learn more about the efforts of Army helicopter crews in the Vietnam War, visit The Legacy of Valor: Vietnam Helicopter Images and Artifacts. Specifically, you can learn more about the hand-painted helmets and the men who wore them in the helmet art section of the site.)

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters Blueprint for the Occupy Movement? Read the Protest Manifestos of the 1960s

Blueprint for the Occupy Movement? Read the Protest Manifestos of the 1960s Military HelmetsThe need to protect the head in battle has inspired a range of solutions ov…

Military HelmetsThe need to protect the head in battle has inspired a range of solutions ov… Vietnam WarThe war in Vietnam (sometimes misspelled Viet-Nam) remains the longest conf…

Vietnam WarThe war in Vietnam (sometimes misspelled Viet-Nam) remains the longest conf… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Another great article Lisa!!

Question

ould you give me the percentages of the helecopter Pilots that never returned?

Lisa – Great article. The amazing thing about the chopper pilots in the Army is that a lot of them were not college graduates like the Marines and Air Force. They were also crazy as hell. They would stay up till all hours drinking then fly the next morning. If you needed them for medevac or gunfire they’d come in anytime or anywhere, 24/7, night or day, under fire or not. We, grunts, adored them! By the way, we called what Larry did Hunter Killer Teams and the guys that flew the Loches (LOH) to draw the fire for the Cobras had to have been the craziest of them all (definitely not pejorative). – George (Thompson’s Dad)

Ed Duncan asked, “Could you give me the percentages of the helecopter Pilots that never returned?”

Ed, of about 40,000 helicopter pilots serving in Vietnam, some 2002 of us did not return; what’s that, about five percent? The total of non-pilot crewmembers killed was 2,704, according to records of the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots’ Association.

I always liked the subdued look of combat zone attire, as opposed to anything shiny or glittery. I found a can of olive drab (OD) spray paint and covered my flight helmet with a single coat. Then I sprinkled some beach sand evenly over the entire surface and topped it off with another couple coats. The result was a very cool, dull, rough finish which set it apart from every other helmet.

I managed to hang on to that helmet through the remainder of my Army tour and still have it (with original Army-issue helmet bag) to this day.

Loved the article!

My Husband is a Vietnam Vet and has many friends who flew these life-saving aircraft. Once, one of the vet pilots teasingly said to me:

“Know how to tell a Vietnam Copter Pilot?”

ANSWER:

“Just give him 5 minutes and he’ll let ya know he was one!”

Hahahahahaaaa…

(A great punchline for an honorable and appreciated group of veterans.)

The gentleman that graces the top of this article is John Hyatt. He and I were Crew Chiefs in C Troop (Air) 16th Cavalry stationed out of Can Tho Army Airfield in 1972. That unit was the last US combat aviation asset in IV Corps which meant we flew a lot of missions. Most of us painted our helmets and aircraft with a variety of personal or unit emblems. The aircraft nearly always had Unit related logos. Helmets? Anything you could think up! I’m an old retired Army First Sergeant now and my crowning glory in the Army was when I was flying combat missions with this remarkable Air Cav unit and the men associated with it.

How old was the youngest army helicopter pilot to fly in the Vietnam War just curious I was 19years seven months old when I arrived in Vietnam as wo1 after a year in Nam and several medals including the DFC and a purple heart when I got home I wasn’t old enough to buy a beer lol.

I WAS A CREW CHIEF IN VIETNAM. 1 IN 18 PILOTS NEVER MADE IT HOME.

THANKFULLY MY PILOT ROGER SADLER BROUGHT US BOTH HOME.

I was a Army Infantryman in the 9th Infantry Division. I served in the Mekong Delta in 1969. Great article and pictures. If you look at the last picture in this article I believe that the helmet is from VMFA-115, This is a USMC F-4 fighter squadron stationed in DaNang. They were the “Silver Eagles”. One of my VFW buddies was a pilot in that Squadron in 1970 and was hit by AAA fire on a mission near the VN/Laos border. He made it out over the South Chins Sea and punched out. Was picked up by the Navy, F-4 is still under water.

John Hyatt the pilot with the orange helmet was lovely looking, a handsome pilot.

I downloaded his image for my album.

What does he look like today?

Great article! It would be wonderful if they’d collect as many of these photographs, quotes, recollections and anecdotes and publish them in a book much like they did with “Vietnam Zippos” by Sherry Buchanan.

CW2 Lowell Enenix found out that his pink helmet drew a lot of attention when he when on a mission as my co-pilot to deliver ammo to troops who were running low on ammo. When we started our climb out from the outpost enemy fire put a crease alongside is pretty pink helmet. Don’t know if he ever wore it away from our base again.

I flew door gunner with Huey pilot Rick Schwab in 1971 when I was with C Troop (Condors), 2/17 Cav, 101st Abn Div. flying out of Quang Tri, Vietnam. Our unit logo was a condor with the motto, “patience my ass, I want to kill something.”

During my first tour I had drawn a Well endowed lady on the back of my helmet. The CO

called me in one day and told me that since some of my passengers might be VIPs that maybe I should cover my ladies boobs. That night I put a set of dog tags on her and I admit it gave her that military look !

I was a crew chief for the 197th and 334th helicopter co 66-67 got my helmet painted want a picture of it my chopper was Double Trouble / whiskey and women named after my fathers B-24 in World War 11

Like pilot Hyatt, my dad was a pilot in the army in nam, it the dark horse squadron, his name was Frederick L Jennings. If someone knew of him please contact me. Thank you

I was a birdog pilot in the 21st RAC, Tay Ninh VN, but a slow hand salute to all the helicopter crews who were all over Vietnam. God bless them!

Wanted to let everyone that knew my brother John he passed away on Sunday the second of May and I miss him a lot.

My dad, Bob Payne, was a tech rep for Bell Helicopter. He was in Da Nang in 1969.

Back home, the WWII vets were well-supported, and when they returned, everyone adored them. Soldiers in Vietnam received news from home within hours, which the men in WWII did not, and it was not always favorable.

Great Article , But I do have one gripe with it, in Relation to the comment about “Easy Rider” the film and Peter Fondas Helmet.. Peter Fondas character was called “Wyatt”… ” Captain America ” was the name of his Harley.