Tis the season for buying presents. As you peruse your local mall, you might find yourself drawn to beautiful geometric patterns in vibrant colors, long associated with Navajo rugs, Pendleton “Indian trade” blankets, and Southwest Native American pottery. They’ll be everywhere you look, on sneakers, pricey handbags, home decor, and high-fashion skirts, coats, and jackets.

But many Native Americans are less than thrilled that this so-called “native look” is trendy right now. The company that’s stirred up the most controversy so far is Urban Outfitters, which offered a “Navajo” line this fall (items included the “Navajo Hipster Panty” and “Navajo Print Fabric Wrapped Flask”) before the Navajo Nation sent the company a cease and desist order that forced it to rename its products. Forever 21 and designer Isabel Marant also missed the memo that the tribe has a trademark on its name; thanks to the Federal Indian Arts and Crafts act of 1990, it’s illegal to claim a product is made by a Native American when it is not.

Chief Joseph wears a Pendleton blanket in 1901. He is famous for leading a long-standing resistance to the U.S. government, which had ordered the Nez Perce to move to an Idaho reservation. Photo by Major Lee Morehouse, courtesy of Bob Kapoun, via “Language of the Robe.”

“The problem,” says Jessica R. Metcalfe, a Turtle Mountain Chippewa and doctor of Native American studies who teaches at Arizona State University and blogs about Native American fashion designers at Beyond Buckskin, “is that they’re putting it out there as ‘This is the native,’ or ‘This is native-inspired’. So now you have non-native people representing us in mainstream culture. That, of course, gets tiring, because this has been happening since the good old days of the Hollywood Western in the 1930s and ’40s, where they hired non-native actors and dressed them up essentially in redface.

“The issue now is not only who gets to represent Native Americans,” Metcalfe says, “but also who gets to profit.”

“Our land, our moccasins, our headdresses, and our religions weren’t enough? You gotta go and take Pendleton designs, too?”

Of course, this is not the first time Western fashion has appropriated imagery in the name of aesthetics, as fashion historian Lizzie Bramlett points out in her blog, The Vintage Traveler. For example, the pattern we think of as “paisley”—now most commonly seen on ties—was once a holy symbol of the Zoroastrians in Persia. And throughout fashion history, designers have been swiping motifs from other cultures—from China and Japan in Victorian times, Egypt in the 1920s, and West Africa and Latin America in the ’60s.

But Native Americans have a unique place in the history of the United States. Today, many Native American communities are still reeling from the impact of colonization, which started when white Europeans first invaded their homelands and continued as the colonists established a new order and repeatedly attempted to dismantle the native cultures. That this dismantling should continue at the mall can be especially disheartening.

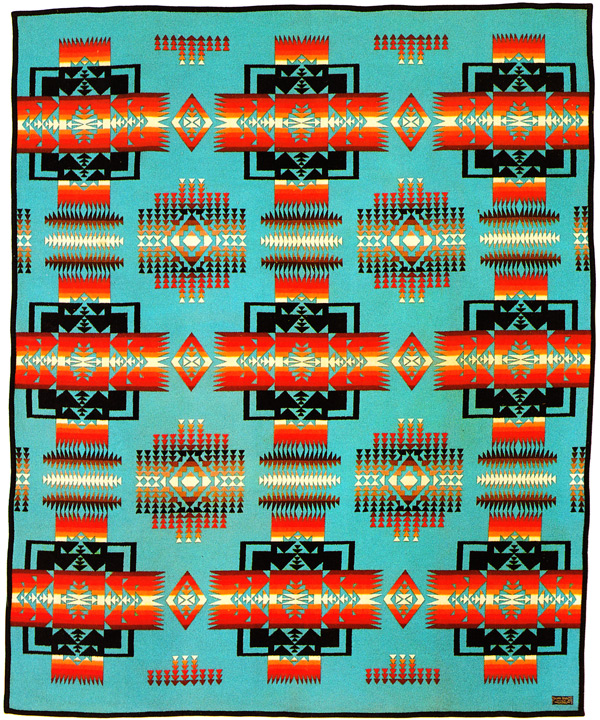

This nine-element robe, named after the esteemed Chief Joseph, was first introduced as an Indian trade blanket by Pendleton in the 1920s. Via “Language of the Robe.”

Even Pendleton, which has fostered warm relationships with various Native American communities since it began producing wool Indian trade blankets more than a century ago, has raised a bit of ire with its new fashion-forward collaborations and collections designed to appeal to a broad, if well-heeled, audience.

Pendleton’s latest foray into young, urban fashion is its fall 2011 Portland Collection, first available in September. For the line, the patterns and fabrics used in the company’s 100-year-old Indian trade blankets were incorporated into high-end cocktail dresses, nerd-chic cardigans, and big blanket-like Tobaggan coats covering the white models like sophisticated Snuggies (models wearing the coats are pictured at top).

This Pendleton travel bag sells for $180 at Urban Outfitters, a clothing retailer that has recently caused controversy with its own “Navajo” line, since renamed.

While these things are trendy and “in the now,” Pendleton blankets have a much more permanent place in Native American culture. In the 1992 book, “Language of the Robe,” Rain Parrish, a Navajo anthropologist, writer, artist, and former curator at Santa Fe’s Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, explains that her family and friends always come to Navajo ceremonies and dances wrapped in their Pendleton blankets.

“As the light from the fire illuminated the moving bodies and blankets, the swirling shapes, lines, patterns, and colors sprang to life. I no longer saw blankets, but rather the familiar designs of the Holy People coming to life from the sand paintings. I saw moving clouds, glowing sunsets, varicolored streaks of lightning, rainbow goddesses, sacred mountains, horned toads, and images like desert mirages—all dancing before my eyes.

“Colorful blankets are often the chosen gift,” Parrish continues. “We welcome our children with a handmade quilt or a small Pendleton blanket as we wrap them in our prayers. For our young men and women, we celebrate the transformation into adulthood, by discipline, values, acknowledgement, and gifts. As they lie on a thick bed of Pendleton blankets, we massage their bodies for good health. For a couple’s marriage, … the woman’s body is draped with a Pendleton shawl, the man’s with a Pendleton robe. As we move into old age, we pay tribute to the spirit world with ceremony, prayers, and gifts. Often we bury our people with their special possessions and beautiful Pendleton blankets.”

Does that make the hip, couture Portland Collection the same sort of exploitation of Native American culture as the Urban Outfitter “Navajo” line? Here’s where it gets tricky: Pendleton blankets, while marketed to and adopted by tribes across the United States, were not originally designed or manufactured by Native Americans. So to understand the debate about the place of what we assume is Native American iconography in contemporary fashion, you have to look at the history of the Indian trade blanket.

These limited-edition shoes, created by Japanese designer Taka Hayashi for Vans Vault in 2010, incorporate Pendleton wool weaves and now sell for hundreds on eBay.

Deep in the Southwest, as early as 1050, the Pueblo people had developed hand-weaving techniques on vertical looms. But the Spanish conquistadors, who invaded the Pueblos in the 1500s, had made their mark on the native weaving craft by the 1600s, seen in the use of wool and indigo dyes, as well as the simple stripe patterns. By 1650, the Pueblo Indians had taught their trade to the Navajo, who eventually developed their own distinct weaving style. They took inspiration from the land, and created geometric shapes to represent the things they saw, like mountains, clouds, owls, and turtles.

“We know that the blankets, especially the Navajo blankets, were inspired by the world around them,” Metcalfe says, explaining that these blankets had a story. “Sometimes, there were references to the geography, but they were abstracted.”

Four young women wrapped in blankets, circa 1890. From “Language of the Robe,” courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma library.

Tribes in the Northeast at the time relied on animal hides to keep warm. That’s why, in the late 1700s, insulating and water-repellent European felted wool blankets became the most coveted barter items for the local tribespeople trading with the Hudson Bay Company in present-day Canada. The most popular of these was Hudson Bay’s off-white, pointed “chief’s blanket,” striped with bands of cobalt, gold, red, and green on either end.

In the late 1880s, when the railroad finally opened the Southwest and the rest of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase to East Coast tourists, white Americans were enchanted with the beautiful geometric patterns used in Navajo blankets. The Victorians would take these blankets back to their overstuffed homes and use them as conversation-piece rugs. Traders, sensing an economic opportunity, encouraged the Navajo to weave these throws with stronger materials and more muted colors suitable for the floor.

Then, in 1895, a woolen mill opened in the Oregon town of Pendleton to sell blankets and robes to nearby Native American tribes. The mill went out of business, but in 1909, brothers Clarence, Roy, and Chauncey Bishop, who came from a family of weavers and entrepreneurs, reopened the facility as Pendleton Woolen Mills.

“The issue now is not only who gets to represent Native Americans, but also who gets to profit.”

Employing the Jacquard loom technology first imported to the U.S. in the 1830s, Pendleton and other new U.S. mills were able to make felted blankets with stunning colors and patterns. Naturally, all the these wool companies looked at the Native American populations, who had at this point adapted wool blankets, often striped or plaid, as a part of their ceremonies and rites of passage, and saw an opportunity.

To Pendleton’s credit, its loom artisan Joe Rawnsley spent a lot of quality time with the local tribes, such as the Nez Perce, to learn what colors and patterns would appeal to them most. As a side note, the Nez Perce most associated with the brand, Chief Joseph, who heroically stood up against the U.S. government for years, had very little involvement with the company. He was photographed by Major Lee Morehouse wearing Pendleton blankets in 1901, but according to Robert J. Christnacht, manager of Pendleton’s home division, that was “the extent of Chief Joseph’s relationship with Pendleton.”

Rawnsley’s early blankets were well-received by the nearby Nez Perce, so the company sent him on a six-month tour of the Southwest, where he lived with Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi to find out what blanket designs those tribes would prefer. He returned with hundreds of ideas. “Baskets, pottery, weavings, and regalia all inspired Joe,” Christnacht says. “Pendleton blanket designs were a blending of the images and colors Joe saw with his own design aesthetic.”

“It’s a crazy cross-cultural mix any way you look at it.”

Some might say that Rawnsley was simply inspired by the beauty of Native American arts and crafts, and he hoped to use his Jacquard skills to make beautiful blankets the tribespeople would love. And in that, he succeeded. Others might argue that this was an early and sly version of cultural thievery. It’s a slippery slope.

“From the beginning Pendleton marketed the blankets to various native communities, but the designs themselves are not authentic,” says Bramlett, a founding member of the Vintage Fashion Guild. “What’s ironic is that the Navajo were making blankets for the white tourist trade, and Pendleton was making blankets to sell to the native communities. That’s kind of a weird twist, but that’s the way it was.

Pendleton banded robe, first featured in the the 1904 catalog and also in the 1910 catalog. Via “Language of the Robe.”

“And the Navajo designs were not even traditional designs,” she continues. “A lot of the motifs that they used were Mexican inspired. Or when traders came to them with oriental rugs, they’d use them as inspiration. So there are oriental motifs in some Navajo weavings, too. It’s just a crazy cross-cultural mix any way you look at it. You’ve got the Pendleton blankets which are a mixture of native and non-native colors and motifs. Then you’ve got the Navajo blankets, which are the same way.”

What we do know is that Pendleton blankets were a hit, and quickly became a staple of life for Native Americans all over the country. They were used at powwows and rites of passage, as treasured gifts, as a means of non-verbal communication.

“Personally, when I think about that history, I think it’s a really cool, the fact that the entire company—and it wasn’t just Pendleton, there were other woolen mills as well—developed because the market for this item was so strong in native communities,” Metcalfe says. “These blankets were integrated right away into our ceremonies. Pendleton also realized that different communities and different tribes had different preferences for designs or colors. And then they created blankets that different communities would like.”

Patricio Calabaza, left, wears a Navajo blanket, and Rafael Lobato, right, wears a Pendleton blanket, at the Santo Domingo Pueblo, circa 1930. Photo by Witter Bynner, courtesy of Museum of New Mexico, via “Language of the Robe.”

At the same time, Pendleton also sold the blankets to white people as exotic items for their homes.

“If you look back at the advertising of the day, it’s vague,” Bramlett says. “They didn’t come right out and say, ‘This is an authentic Navajo design,’ but they could lead you to believe that. They realized there was a market for non-native people to use these in their homes. Heck, they were in business to sell blankets. They didn’t care who bought them.”

All of this to say, it’s very hard to parse out the proper credit for these “native” textile patterns popularized by Pendleton and others—let alone when this appropriation first happened. In the early 20th century, Pendleton blankets seemed perfect complements to the rustic, spare style of the Arts and Crafts movement, and by the early 1910s, Christnacht says the company was expanding these patterns to couch covers, rugs, and robes. Later, they were adopted by cowboys and competitive horse riders as saddle blankets.

“The time when Pendleton came into existence, the 1900s, was the all-time low for native communities,” Metcalfe says. “This is at the height of the reservation era, when we were confined, we were essentially prisoners on these small plots of land. But in that same breath, while our cultures were under threat from this outside force, that’s when we turned internally to protect what we had, and we also get some of the most beautiful beadwork and most beautiful jewelry coming out of that period of great stress.

“Connected with that great assimilation movement was the height of collecting. The late 1800s was when a lot of our stuff left our communities. On the one hand, you have this push for trying to absorb or get rid of ‘The Indian Problem.’ Then, they were taking all of the items that embody that culture, to collect them and put them in museums and claim ownership on them.”

This Tomi Girl dress was made by Lakota designer Mildred High Elk Carpenter, out of a Pendleton blanket, for her MILDJ Native Fashion line. It’s worn by N8tv Dyme’s top model Katrina Drust. Photo by Tiara Carpenter, Native Doll Photography, Bellingham, Wa.

In the 1970s and ’80s, top American designer Ralph Lauren became enamored with Navajo rugs, Plains beadwork, and Apache pottery. He launched his Santa Fe line of clothing featuring concha belts, petticoat skirts, “Indian patterned” sweaters, and blanket jackets in 1981 as another defining aspect of American culture. In the 1990s, the Pendleton and other Native American-inspired designs swelled in popularity again with the return of “Southwest” style and rise of “new country” music.

In recent years, Pendleton has been going to town with collaborations using the iconic Indian trade blanket patterns. It had sold these patterns to Vans, famous for making skateboarder shoes; produced high-fashion lines with Manhattan couture company Opening Ceremony; and it is even offering products through Urban Outfitters. With Levi’s, Pendleton launched a line of jean jackets and cowboy shirts called Navajo Cowboys, hiring Navajo rodeo champions like Monica Yazzie as models.

“The reason why Pendleton was able to maintain themselves—and they’re the only woolen mill that survived—is because of their dedication to the native communities and realizing the native people were their main market,” Metcalfe says. “The blanket for us has become associated with idea of native pride, associated with achievement, community, and community service.

“Now Pendleton’s entering the mainstream fashion scene, doing these collaborations, and it is probably a smart move for them, as a business. But we feel like we have some ownership with this company, and we do question whether they’re stepping away from their relationship with us.”

For some, like Cherokee writer and Ph.D. candidate Adrienne K., who blogs at Native Appropriations, it’s confusing and saddening to see her beloved Pendleton selling stylized products to wealthy young Manhattanites who are as removed from the native way of life as any American could be.

“Seeing hipsters march down the street in Pendleton clothes, seeing these bloggers ooh and ahh over how ‘cute’ these designs are, and seeing non-Native models all wrapped up in Pendleton blankets makes me upset,” she writes. “It’s a complicated feeling, because I feel ownership over these designs as a Native person, but on a rational level I realize that they aren’t necessarily ours to claim. To me, it just feels like one more thing non-Natives can take from us—like our land, our moccasins, our headdresses, our beading, our religions, our names, our cultures weren’t enough? You gotta go and take Pendleton designs, too?”

Monica Yazzie, a 19-year-old Navajo barrel racer from La Plata, New Mexico, models the Levi’s Workwear by Pendleton woolen poncho.

Metcalfe says she’s observed, to her amusement, that the Vans collaboration has been a big hit with Native American communities, but the Opening Ceremony line is dismissed as ridiculous. For Adrienne K., the stratospheric prices of the haute-couture Pendleton items just adds injury to insult.

“There’s the whole economic stratification issue of it,” she writes. “These designs are expensive. The new Portland Collection ranges from $48 for a tie to over $700 for a coat. The Opening Ceremony collection was equally, if not more, costly. It almost feels like rubbing salt in the wound, when poverty is rampant in many Native communities, to say ‘Oh, we designed this collection based on your culture, but you can’t even afford it!’”

This screen grab from the Opening Ceremony web site shows a model in three different Pendleton sweaters, all over $500.

On the other hand, Native American designers, too, like Sho Sho Esquiro, of Kaska Dene and Cree descent, and Mildred High Elk Carpenter, a Minucoujou Lakota living in Montana, have also taken inspiration from the Pendleton blankets, sewing them into to modern fashion items like skirts, jackets, dresses, and even hoodies.

“It’s really cool to see how they reinterpret the blanket,” Metcalfe says. “For Sho Sho, she’s using very vibrant colors and the bold graphics of the Pendleton blanket and giving it this hip-hop vibe, by making these hoodies for men and women. She’s made the wearing blanket something cool for Native Americans to wear again.”

Bramlett says she’s glad Adrienne K. and other bloggers are speaking up, because it’s bringing up all the ways Native Americans have been exploited and misrepresented in mainstream culture. Having grown up in the ’60s, Bramlett remembers a time not so long ago when it was considered acceptable to portray “Indians” as violent enemies in movies, television, and children’s books and cartoons.

Even though the cultural tides are turning, a Cherokee-run company in North Carolina still makes knockoffs of ceremonial Sioux headdresses for children to play “cowboys and Indians” with. And Ke$ha and other young scenesters seem to think there’s nothing wrong with donning copies of sacred headgear for partying at summer rock festivals like Coachella.

“When you see pictures of some of these festivals where young white women are all dressed up in Indian regalia, you wonder, ‘What the heck are they thinking?'” Bramlett says. “What adult is going to do this? Do you not realize you just look dumb?”

The cover of the Pendleton catalog, circa 1901. This 24-page catalog offered blankets and photographs of the Plateau Indians by Major Lee Morehouse. Image via “Language of the Robe.”

And even though she finds fashionistas wearing the high-end clothing made out of Pendleton fabrics much less egregious than concert-goers wearing headdresses, Bramlett says it still can look like children playing dress up. “If it’s something that’s that strong a design that is so strongly associated with one culture, it makes you look like you’re trying to be something you’re not.”

Still, Pendleton, who is also known for folksy Americana plaids (inspired by Scottish tartans) and The Dude’s sweater in “The Big Lebowski,” has to find a way to stay viable in today’s brutal international market, Bramlett says, or it goes out of business—and its beautiful blankets go with it. Christnacht says that 100 percent of the blankets are woven and manufactured in the United States, and half of those, which go for about a couple hundred dollars a piece, are sold to Native Americans. In 2009, Pendleton, which employed about 900 people nationwide, had to lay off 43 workers and consolidate operations in response to slow sales during the recession.

“To stay in business, they have got to appeal to younger consumers,” Bramlett says. “They just have to. And so if they want to collaborate with Levi’s or Vans or whoever else they’ve been in bed with, that’s fine and good. If that industry were to collapse, it would be gone. I’ve seen this a dozen times. Once it’s gone, it’s gone and it’s very soon forgotten.”

A 1910 Pendleton banded robe, also offered in the 1904 catalog as a round corner blanket. Via “Language of the Robe.”

Metcalfe says you’ll never get a consensus from the Native American community on what Pendleton should or shouldn’t do, but ultimately there is a great love of Pendleton, which has often produced blankets to give back to the community, like the one designed by Osage artist Wendy Ponca that benefitted the American Indian College Fund. It’s just—like you do in any long-term relationship—they get a little annoyed with the company sometimes.

“I think ultimately the collaborations are a good thing because they’re opening a door to greater understanding,” Metcalfe says. “Hopefully, those people wearing these clothes will learn a little more about Pendleton’s history and why we have respect for Pendleton. It is because their sense of service to native communities.”

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

Uncovering Clues in Frida Kahlo's Private Wardrobe

Uncovering Clues in Frida Kahlo's Private Wardrobe The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets BlanketsThe first time any piece of cloth or bedding was called a “blanket” was in …

BlanketsThe first time any piece of cloth or bedding was called a “blanket” was in … Native American Rugs and BlanketsIn many ways, the story of antique Native American rugs (sometimes referred…

Native American Rugs and BlanketsIn many ways, the story of antique Native American rugs (sometimes referred… Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in…

Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Lisa — great article! Love the mix of vintage and new pix. The Pendleton robes are gorgeous. The conflicting views made for a good read. How can anyone ”own” these artistic ideas, when they are a mix of many culture’s influences? But emotions aren’t logical. We need to try to be more sensitive, which apparently some of the businesses claiming ”authenticity” aren’t. Hopefully your article will raise some awareness.

Incredible article! Thank you. I religiously read Jessica’s blog and the Native designers she features do amazing work.

Instead of the forever21 made-in-china ‘tribal tees’, etc that I see plastered all over the blogosphere, it’d be nice to see some Native designers receive more publicity and attention in the mainstream market. This article is a good start. Who’s next?

About as balanced a take on the issue as I could have hoped to expect. Nicely done.

Pretty much what we consider Native American “design” is an amalgam. The earliest “symbols” can be traced back to paleo-Indians (pre-modern tribal designation). Then you have — from the 1500s onward — items fashioned from “trade goods” from Europeans. Finally there are the “made for sale” items such as the blankets that were instituted by Fred Harvey and others to sell as souvenirs at their railroad site venues. “Authenticity” is difficult to say the least to define. According to my mitochondrial DNA, I descend partly from”paleo-Indian” stock. Does that make me any less a Native American? What if I do crafts based on Native American symbols and styles? Are they authentically “Native American”?

Great article. Waaaaaay too many links though. Took me two hours to read it!

I really appreciate this article. Good work, my girl!! There are so many issues at hand in regard to cultural appropriation vs. cultural appreciation… The main one being nicely handled here: The historic trauma that Native peoples have endured is still an unresolved wound. THIS is what makes some Native peoples pissed off about the fashion trend. If and until the trauma of genocide is adequately healed, issues such as this continue. Someone from AIM recently said, and I paraphrase: “We know most of the members of “white society” today are not directly to blame for the genocide which began 500 years ago, so we don’t blame “them”… BUT today’s dominant society still reaps the benefits from that genocide while today’s Native peoples still suffer the aftermath.” This fashion trend is symptomatic of that hard truth.

The Hispanic and Mexican weaving traditions that were such a huge influence on Navajo weaving continues to this day as Chimayo weaving. You disregard this living tradition. I’m not sure how happy I’d be if I really thought the fashion world was stealing from us, but we certainly work with a very closely related design vocabulary to what is pictured here. Only we’re doing it all as handwoven products.

Despite the fact that I look Caucasian (my father was English/French with American roots to the first colony), I am also Yupik/Cherokee born from a mother who is part of the “lost generation” of Native Americans due to being displaced from Tribal Affiliation and Heritage in the government inspired “re-education” in early part of the 1900’s. My point is that there is an ongoing “lost generation” as we inter-breed and the lines of Ancestry in America are no longer clearly drawn. For those of us raised in the vacuum of Western Civilization without a defined heritage, and rejected by the Native Americans around us, because our blood is not “pure” enough, sometimes our only way to honor our Ancestors is by dressing up and pretending. This could be one explanation for this trend. I respect the American Natives for wanting to preserve the integrity of their culture, and that I can always look to the pure Yupik or Cherokee Nation for authenticity; however, we are also all part of a World Tribe in which creativity, and the use of old ideas in a new way is appreciated, and also Honor’s our Ancestors.

Great article BUT,it leaves me wondering…I am full blood (Creek, Cherokee and Comanche), I married a “white man” and we have three children. And while all three have Indian features…one son has dark hair, brown eyes and olive skin. One son has red hair, green eyes and reddish/olive skin, and our daughter has blond hair, blue eyes and light skin like her dad. So if my daughter wears “Indian” patterns and styles she is going to be looked down upon by my own people because she doesn’t fit into what Indians think an American Indian should look like?? My daughter is just as much an Indian as any “full-blood”. While I agree that “Indian Made” should mean just that…to judge people because they don’t look Indian enough or “white” is hypocritically racist.

I’m sorry, sisters and brothers, but in the 1970s I made a wish that everything in our (Indian) country would be Indianized. I did this so that the world would know they are in Indian country. Knowing this wish, and seeing clothing, jewelry, and other designs doesn’t bother me. Money isn’t going to last anyway. This was told to us in the 1970s. I now live in cluster housing right where I, as a child, wished there would be cluster housing. If you want me to wish it all away, I would have to think very hard about doing so.

It is always dissapointing when vulgar language goes mainstream. It’s not even in the body of the article where it is buffered by a paragraph or two. It is glaring in the title where it boasts, “yeah, I said that!” I am used to a higher standard from CW not the lowest common denominater used by most media. Just my opinion…

I get mad every time i see a white person wearing native american design

Cherokee Apparel is a name licensed to any company who wants to use it. The parent company is based in the U.K., and it should be illegal to sell clothing using the tribe’s name in America under the Indian Arts and Craft act, but Target and other stores still sell the line.

BUY INDIAN – ACT NOW! One thing is for sure, when you buy from the Indigenous artisan you know you are getting “one of a kind”. They will even custom make a coat, bracelet, dress, shawl, etc. for you! And they make pennies compared to those mass produced. I am thankful that our people who are gifted to have the vision to create works of art have not given up. Unfortunately, many would be “buyers” walk past these fine works and go straight to the shops to spend mega bucks on a “coach” product. Thus, contributing to the “others” economy! Thanks for the article.

” So now you have non-native people representing us in mainstream culture. That, of course, gets tiring, because this has been happening since the good old days of the Hollywood Western in the 1930s and ’40s, where they hired non-native actors and dressed them up essentially in redface.”

I disagree with the quoted. The difference now is that people aren’t dressing up as Native Americans and making claims about them, or “representing them”. People are recognizing a beautiful pattern they have affinity for and are probably aware of the fact that they themselves are native-inspired. What does that mean? It means that people relate to the values that they see indigenous people stand for. Care for nature, community, ancestral roots, ceremonialism, and a spirituality not limited by western dogma. Does everyone think about it this way, even as they wear native inspired patterns? probably not. Some just think its cool and are following the crowd. But Native American patterns aren’t the only ones hitting the mainstream. African, Egyptian, and many more are becoming popularized. Why? Because Westerners crave the concept of Tribe. All our ancestors at one point were tribespeople. And the aesthetics of disparate cultures from the reindeer herders of Northern Sweden to the Tibetans have remarkably similar fashion tastes. Maybe we are all reclaiming our indigenous us. That includes what we wear, what we eat, who we relate to, and how we honor all of the above. The next step is education. not just pretty patterns, but where did this come from and what does it signify. Perhaps in the future we will all wear patterns designed by us but derived from all historical and cultural symbols that we hold dear and feel define us. As for now, I think wearing a native design is as close as we can come on this day and age to saying “proud to be an American”. I don’t think the Stars and Stripes satisfy anymore.

does someone of south american Mestizo descent have the right to wear North American native clothing?

Does this mean i can get away with wearing my breech cloth to the mall? Hopefully this doesn’t drive up prices on Pendleton Blankets. At least in a couple years, there will be a ton of this stuff in thrift stores and on ebay, and these goofballs will move on to the next trend. Maybe everyone will start growing beards and wearing neon rayban knock-offs. Oh, wait………

I’ve heard many stories from my grandmother about how our people were given choices. With this information of how Pendleton became inspired by the designs the Dine people (aka Navajo) and other tribes we should embrace what they have done. We have been acknowledged and it was their idea of mass production of these blankets. Though weaving is a soon to be lost art to our tribes, we must understand that the original designs are what we have come to know as a symbol of life. Out of respect to the elders we should not be fighting over who did it first, it should be expected that we grow to learn that we have to survive in ways unexpected. We should not take what is not ours to begin with. It just so happens we have inspired this idea. There are far more important things to worry about than rights to a design. Such as, giving back to the people who helped these successful businesses by supplying the very products they produce to communities that need it most. It should not always be about money but I am so glad that we have the trademark to protect now.

I’m pleased with this article, I did not know the full history of Pendleton or it’s inspiration.

What I’d like to know is how it is that so many restaurants offer Navajo tacos, when the business is not owned by Navajo descendants.

my personal belief is that squabbling over money and ownership is not what art is about. Making something first is also not the most important thing. This is all the aftermath of human ego getting in the way of larger questions about reality. Yes people have been abused in history, all over the world, and yes those harmful betrayals should be rectified (as best they can be) because many things are not reversible, but art and fashion and free speech and expression are ultimately untied to history. Symbolism is a figment of our imagination. victims and aggressors have equal rights to symbols, aesthetics, and elements. Ownership by individuals or so called ‘groups’ is a problematic capitalist concept to begin with. How is a design mine? How is a pattern mine? How, or better yet, why do i need to assert my dominion over those colors and shapes. Is it so i can profit as much as i can while I’m alive to reap the benefits? In the long run, the long run of universal time, not the thwarted sense of time that we get stuck in, these questions of appropriation, theft, copying, mimicking, buying and selling, really don’t matter. What matters is how we treat one another. How we let go of the past. How we share what we have. Generosity of spirit goes both ways, from one tribe to another, regardless of transgressions, and as Bob Marley once said… ‘Every little thing, is gonna be alright”

This is a great article. Thank you for your time putting this together. Really well done.

This is a great article because it demonstrates all the contradictory ideas and practices. I recently discovered Pendleton blanket designs when I was offered a blanket as a wedding gift. I was very intrigued when reading about the history and Pendleton’s historic relationship to Native Americans. I realized there was and is exploitation of ideas and of peoples, but at the same time, as an American, I’m proud that the mills still exist. My 80 year old family members have great respect for the brand, as I do, for the long lasting quality. I can’t afford to purchase it new, I look for used Pendleton. When I wear a coat with Native American designs, it is with pride for the many cultures that exist in my country, respect for their art and culture and appreciation of their beauty. I am very aware of the suffering (past and present) of Native Americans and always made a point of teaching it to my English students when I lived abroad. I was glad to see that Pendleton makes some effort to give back to the Native American community. Although I am of European descent, I would hope Native Americans could see some trends as a celebration of their culture and an opportunity to instruct the general population and raise awareness about the needs of their communities. Certainly I understand the irritation caused by a vendor representing something as authentic Native American design or trivializing their culture, but perhaps the popularity of Native American inspired designs could help bring attention to Native American culture maybe even increase donations to the needy in the community and incite young people to learn more about Native American history.

Native Americans have sold their crafts and garments to non-Native people for a good many years now. They also wear White-man clothes. So why do they have any reason to be upset over what someone wears regardless if it resembles a Native print or not? That’s just silly! Are they upset if someone is wearing a style from some other culture; Hawaiian shirts, Wooden shoes, Peruvian jackets, Chinese style shirts, what-ever. Probably not. Grow up and let it go!!

–I get mad every time i see a white person wearing native american design–

Why? As long as they are not pretending to be native american, why should it bother you? I’m Japanese-American and I don’t get upset when people wear yukata or clothing with Japanese designs. They simply appreciate the designs for what they are.

I do think that associating a product with a particular group is bad, but being inspired by the designs themselves is just silly.

I can honestly understand why they’d be upset that their name was being used to hawk wares like dream catchers, but to get indignant over your cultural patterns being used for handbags, sheesh. I imagine there are plenty of Scotch-Irish that would be plenty pissed if they saw all the plaids in my closet.

–I get mad every time i see a white person wearing native american design–

And on the flip side do you likewise choose to be angered when you see Native Americans wearing white design?

Immensely awesome article, too bad same can’t be said for a number of the commentsu that come off as ignorant or whitesplaining in how I should feel about my culture, itsappropriation, misrepresentationand theft.

Three points:

1.

I’m not going to pretend to know too much about it, but as I understand it, Navajo rugs get their serrated, diamond patterns from the Mexican, Saltillo serape which probably has a Mexican-native origin that I’m not aware of. Those diamond shapes are not really part of the Dinetah landscape.

2.

I think restriction and ownership are impossible in this post-modern market, but the issue seems to be understanding and respect, in the words of traditional pueblo weaver that I wont quote by name “When I weave I pray so that the garment protects the owner” that’s a kinda heavy thing to pretend to. One should know what the designs represent and where they come from, it’s not about how much native blood you have (although it seems to be for some people right now) its about knowing enough to honor it by wearing it, which isn’t as easy as it first appears.

3. as well written as your article was, by the end the whole thing felt like a pendelton love-fest.

My thoughts, pardon my ignorance ahead of time.

–whitesplaining–

And that racist remark says all we need to know about you…

Should there be a policing agency responsible for “clothing licenses”? Who draws up the rules about what clothes each of us can wear? Can any member of a culture decide for the rest of humanity exactly what is acceptable? I’m an eighth Choctaw, so do I get approval for a wallet with a native design, but not a shirt? Or only if it’s a Choctaw design and not a Sioux one? Could an Indian ban English shops from carrying saris?

The Navajo have every right to complain about their NAME being used for marketing, but that’s about the extent of it.

And I’m not white, since that’s probably a big thing for you.

Declaring a contrary view to be “whitesplaining” is a way to simply shut down any real discussion. It’s also racist. How would you like to hear your view called “blacksplaining” or “indiansplaining”.

These are patterns made by a company from myriad sources, including Navajo, Mexican, and Asian design. If you don’t like that some people like them, too bad….I’m sure some Scots hate the plaids people so casually wear…but then they are white, so their views don’t matter to you anyway.

I DO agree that they should not be calling it Navajo. The people are not a brand. Call it “Western” call it “Tribal”, call it “Desert”.

“It’s a cross-cultural mix any way you look at it”? Bullshit! What is the mix exaclty, our ancient, sacred, cherished designs with the super trendy, played out hipster look and lame culture that just won’t go away? Who gets paid for our artwork? Not us. Non-natives have been making money off of us since they stepped first foot on our beach. It would be one thing of they donated a respectable amount of this easy money to our people to maybe help us out of the horrid mess we’re in right now, but probably not. What is up with this “hiptser” culture anyway? Looking at them through my eyes being low-income, Native American public housing resident born and raised in Seattle, they bug in many of ways, they’re mostly a bunch of spoiled, snobby, shallow little jerks that rape their way into cultured, soulful, colorful, diverse, neighborhoods and completely destroy them by having the rent raised forcing minority families, businesses, and sense of community right from under us, and now they’re grabbing our artwork. Why is it all of our artwork is for sale everywhere, authentic even, but yet so hard to sell? Why does it take a non-native to sell it? That isn’t fair. We as native people teach that we need to give back from which we take, so should you. I vote NO on the theft of our culture, you already have our land.

First, I would like to address the “Get over it comments.” Those moments in history have a strong impact on our lives as Natives Americans (politically, socially and emotionally). Just the same way the Bombing of Pearl Harbor has on all of our grandparents or the events of 9/11 have on our lives. Native Americans have a strong tie to our ancestors, we honor their struggles and bravery. To get over it means to forget about our ancestors. We honor our past and I am sorry but we will never get over over what happened in the past. However, I am a strong believer in tolerance and we all, Native Americans included, need to tolerate each others culture, history and now even apparel choices. I am a Native American that wears White clothing. I gave my best friend, who is White American, a pendleton blanket, pottery and a turquoise necklace. I have seen many Non-Native Americans wear Native American or inspired clothing and I see other cultures wearing White clothing. Maybe some White people are trying to dress like Native Americans which is great but I also see many Native Americans trying to dress like rich White Americans. Both groups don’t fit the biological makeup but they both have the right to dress however, they like. Products not made by Native Americans should not have the right to claim “Authentic Native American Artwork”. There is greater value when anyone and I mean anyone buys handmade artwork whether it is clothing, jewelry or pottery from a Native American Artist. The artist can tell you more about the design and the meaning than a store retail clerk can. This being said support Native American Artists whenever you can.

Like too add, anyone using the argument of us wearing “white clothing” as a counterpoint is full of it and fails in understanding history or even the dynamics of power from history as too why we, or any culture that’s isn’t white, wears such clothing. Here’s a hint: it’s wasn’talways because we wanted to.

I will no longer buy anything with any hint of Native American influence or design. Even if I buy it from a Native American designer or maker, it is still likely to offend someone because I am white and do not have the cultural connection required to wear it. They have no way of knowing that you are aware of the destruction of the Native American culture…they will likely see you as unjustly appropriating it (see comment 12 above).

Native American fashion and design is for the exclusive use of Native Americans and no one else. Buying these goods, from whatever source is an unwarranted trivializing of the struggles faced by Native American people.

Thanks for the heads-up and the consciousness-raising.

What many do not realize is that by Native extremist groups claiming that non-natives have no right to wear Native designs, they are creating problems for Native artisans who’s entire livelihood relies on the sale of Native goods. I have actually seen people state online that they would no longer buy anything with a Native designe on it-Native made or not!

What they also fail to realize is that this is the way ALL designs come about…all around the world and throughout history. All of the designs are reworked, borrowed from each other and OFTEN not “traditional” but came from other people. Obviously none of these people know of the Native Curio Trade- designs that were INVENTED in conjunction with non-native traders in the 40s and 50s to satisfy non native customers…many of these designs are now looked at as traditional

While I have every reason to be sympathetic to the extreem use of mega-corporations abusing the situation by misleading people to believe that a line of Chinese clothing is somehow connected to the Navajo Tribe for example, I MUST ASK HOW ANYONE COULD BELIEVE THAT ONLY NATIVE PEOPLE HAVE THE RIGHT TO WEAR NATIVE INSPIRED DESIGNS??????

Do only Jewish people have the right to wear Jewish designs? How about Africans? Do Afro-Americans get to wear them? Who decides? Do we have to start a registry to decide who is black? Barack Obama is half white (REMEMBER?) Can he wear African designs?

This is where the aversion to activism comes from…It is time to start choosing the correct issues to take on and remember that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”

its just…a never ending issue, all sides, culture, history, art, racism, starting to become a conundrum. ugh.

Very well written article. It will be helpful to anybody who usess it, as well as yours truly :). Keep doing what you are doing – looking forward to more posts.

I guess Indians should not wear cowboy hats and boots. That is silly of course. Each person can choose to dress as they wish.

As a fashion student we are encouraged to research different cultures and look deeply in to history as we design. We take details from these points in history and adapt them for modern day. Being inspired by the past is the core principle of creating something new. It seems ridiculous to me that a group of people who are clearly proud of their ancestry would not be flattered by people simply drawing inspiration and recreating something that from their past. If we were to argue this point over fashion as a whole there would be thousands of referenced races and groups of people who would be up in arms about us ‘stealing’ from them. The fact of the matter is, it is not stealing at all, it is a widespread appreciation and love of this type of design.

I agree with Hurna’s comment:

tive Americans have sold their crafts and garments to non-Native people for a good many years now. They also wear White-man clothes. So why do they have any reason to be upset over what someone wears regardless if it resembles a Native print or not? That’s just silly! Are they upset if someone is wearing a style from some other culture; Hawaiian shirts, Wooden shoes, Peruvian jackets, Chinese style shirts, what-ever. Probably not. Grow up and let it go!!

Should I be insulted or angry every time I see a native girl wearing the same brand of jeans my daughter does. Should Native North Americans be wearing only their traditional dress? I believe there would be a great cry of “discrimination” if that were the case.

Every culture has its patterns & colors. If I like something I have every right to wear or display it ~

I think Native art is BEAUTIFUL! And should be shared. As a Native American, I feel good knowing that my daughters have the option to wear any design. Seeing the designs in the stores (even Target) I think of my Grandparents. Having the design “mainstream” makes me feel less invisible.

Wearing a pattern doesn’t mean your mocking the culture. Take it as mainstream America/hipsters FINALLY appreciating a piece of our culture.

Two questions that were not addressed were, where did the Navajo get there sheep? And what type of sheep were they? A little research will get you the answer. The sheep came from the Spanish. They are descendents of Churra an ancient Iberian breed. They were prized by the Spanish for being remarkably hardy, among other things. The Churra were the very first breed of domesticated sheep in the New World. Wool weaving was taught to the Native Peoples by the Spanish. Anyone who does a little research about the looms used, also will find that the historical Navajo did not weave on blanket looms but on looms more suited to rug making. Their looms were later influenced by the opening of trading posts and European traders. To try to claim any sacred trademark is impossible when the credit for the very ability to weave is so solidly linked to the Spanish Conquest of the New World. By the 1600’s the Churro sheep were the mainstay of Spanish ranches and towns in the upper Rio Grande Valley. Now it is a historical fact that the Native Americans first availed themselves of these sheep in two ways, by trade and by raid. So within the next one hundred years, herding sheep and weaving became a major economic boon to the natives.

So on the one hand you can hate the Spanish for invading but without them and others that followed, the Navajo might never have become the great weavers that they are today and nobody would even know what a Navajo blanket is.

All countries in their histories have been invaded and lost some cultural identity. How we respect one another today and appreciate all the cultures that influence our modern society is the only way to remain healthy and non-divisive. One cannot suddenly claim something as sacred and exclusive which is impossible to prove originated with one culture. It would be like Hawaiians suddenly trying to claim the fabric by the same name is sacred to them when the whole thing was started by a fabric maker in Mansfield, England.

I am so sorry to read this a article-the saddest gut wrenching sight is to know of or see a native american indian chief’s head-dress (imitation) worn by a white man or one bought as a present to go in white man’s home on display. The history-the tears – the sadness of this could not possibly bear a white any blessings Tia Fawn Southern Medicine Woman-you can forgive some comments above they have no idea! Yes it is stealing from our heritage-but some of the above cannot feel our heritage-but should read some to obtain knowledge.

I am full bloodied Native American half Zuni and half Navajo, and I live in British Columbia but born and raised in New Mexico. As I navigate my way through downtown Vancouver there are a handful of gals who wear this “Navajo” trend. And stores are loaded with this stuff. Although I should be offended, I’m rather amused because its just a trend and it will eventually die away. So people should just calm down about the whole thing and just relax. I catch myself wanting to take pictures of these guys and gals decked out in their clothes from Urban Outfitters because its silly. People are entitled to wear whatever they want, I wear the white mans clothes, you don’t hear them complaining about that and wanting them to take it back. We all borrow ideas from one another and we should just live happily amongst each other. Until we see Non-Natives wearing our Kachina masks and trying to practice our religion-that’s where we draw the line. Until then there’s really nothing you can do about retailers selling Native inspired clothing. I come from a family of artists and silversmiths and I only wear jewelry made by my family. So if you wish to wear Native American Jewelry, find an authentic local artist and buy from them. It’ll look less tacky and be authentic.

Now my fellow Natives, break out your concho belts, squash blossom necklaces, and embrace that everyone wants to look like us!!

MISSING THE POINT!

The issue isnt about Natives opposing people wearing Native traditional clothing patterns etc (most Natives dont have issues with that). Its about CULTURAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS and TRADEMARK RIGHTS.

eg If you did a piece of art or wrote a book or composed a song or wrote a script for a movie or patented a new invention etc. does that mean someone can come along slap their own name on top of yours and use it (for personal profit) without your permission and without proper compensation?

The issue is Financially using someone elses culture for personal profit and giving nothing back to those impoverish communities they took from. It becomes a legal battle matter.

I’m full blooded Khe-wa from Santa Domingo. I dont know if you noticed but the native guy in the um older picture is my relative and obviously he is wearing a letterman jacket, this is similar to a white american wearing native patterns/jewelry. This is called cultural diffusion, thought this happened through out human history. So please stop being over analytical and slightly racist on the fact that we wear white man clothes. Anyone can wear what they want just as long as it is not used in a discriminative manor. Which means people should read into items that have certain deeply cultural and cerimonial meaning to them like headdresses, because with out the knowledge of such things then there is a non intended offensive arrogance.

However the more important issue is the capitalization of products that local artists sell to have necessities. Coming from a family of silversmiths, jewelry makers, and potters I personally know how these goods support native families. In fact some of my earliest memories are of helping my grandmother in Santa Fe as she sold jewelry on the streets. Kinda beating a dead horse here, but like with any good or service, supporting a local artist, farmer, or business helps the community and puts money back into the pockets of hard working Americans. I’m not trying to rant about the pliet of the american artisan , I just want to point out a reason for peoples anger with a possible solution.

On another note MKO is quite right haha

We have worked with Vans for 4 years now making some limited Ed. Vans Pendleton shoes that 100% of the profits go to our Native Non-Profit Nibwaakaawin. I just want people to know that Vans has made our outreach to native youth possible!

being from pendleton and a enrolled member of the confederated tribes if the instills indian reservation.I’m proud to receive and give blankets. going to the mill suite is a addiction.one thing that makes me upset about the clothes is that they are not durable add they used to be.pants and shirts are super thin.it was started for the workers who would work in the fields or grain elevators and what not. niue I betty I current even catch a snag on a barb write fence without tearing it apart. the new line is sad. the new owners are trying to make sure we can’t use our own towns name. its just proof that rich puerile can ruin the true meaning of what makes toss country great the heart and soul

While non natives are making a profit real natives live in poverty and make no benefit from stolen ideas fashion and culture style . It also go with spiritual items that are being sold even to non natives like sage for purification from negativity and bad thoughts. just recently a non native guru was selling Sweat Lodge ceremony for thousands of dollars and murdered other non natives in the so called Warrior Sweat. People make a mockery of native people from sports mascots to history as a war like people instead of showing what natives contributed alot to our daily American lives. Doctrine of Discovery is an insult and supremacy to the point of culture genocide upon first nation Native Americans. This is racist and insensitive toward Native Americans and the predominant society the can afford these businesses don’t help local businesses of real Native owned businesses and all made in china items should go into a lawsuits and legal representation as the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990

Public Law 101-644 has done for fake non native owned items coming off as authentic Many people dont know what the symbols mean and many natives lost there culture and identity and want to have something to identify with so they use these products and once again it is mislead our people and especially our youth and most of all of you non natives! If support native buy from native owned businesses thank you all my relations hau!

I be going after them in court and then Royalties….Yippers ….Thats copy righted stuff….There they go again stealing stuff or as some would say borrowing Indian Time…I’d sue them for half at least….

Great article!