This article on William Gilbert, Jr. notes the New York silversmith’s family life, craft, and influence, as well as his extensive military, political, and community involvement in the 18th century. It originally appeared in the July 1941 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

When Gerrit Cosine, or Cozyn as the name was spelled on the old Dutch records, died in 1769, he bequeathed to his daughter Catherine “his Mahogany Dining Table, his Mahogany Card Table, his Looking Glass,” and a carefully itemized list of articles which included “a silver tankard, marked G C, and a silver teapot, silver sugar box and cover of silver, 6 silver table spoons, 6 tea spoons, silver tea tongs, silver mug, and silver Punch ladle.”

Silver Mug by Gilbert: This piece originally belonged to Nicholas Bayard and bears his family crest on the side. The shaping of the handle is unusually bold.

In a way this legacy was in the nature of a load of coals for Newcastle, for Catherine’s husband was William Gilbert who, at the time, was a rising young silversmith of the City of New York. In Cosine’s will his son-in-law was referred to as W. W. Gilbert, and this was the appellation by which this craftsman was generally known, although he was baptized in the Dutch Church in 1746 as plain William, the son of William and Aalte (Verdon) Gilbert.

Undoubtedly, he adopted the extra initial as a convenient means for distinguishing himself from the many other gentlemen of the same name then resident in New York. For instance, at that period there was a William Gilbert, baker, who had a son William Jr., a few years older than the silversmith.

No record has as yet appeared of Gilbert’s apprenticeship. Very possibly he served under the same master as did another prominent silversmith of the time, Ephraim Brasher, as the latter married William’s sister, Ann Gilbert. But evidently young Gilbert finished his term at a rather earlier age than was customary, since he and Catherine Cosine were married in 1767 when he was barely past his twenty-first birthday.

Sugar Bowl by Gilbert: The urn shape was a favorite form with this silversmith. This piece, with "bright-cut" engraved decoration, bears the monogram T H L in the oval beneath the balancing leafage sprays on the side.

At that time the spirit of resistance to arbitrary acts of the British Government was growing rapidly in America and, from the first, Gilbert identified himself whole-heartedly with the patriots. In spite of his comparative youth, early in 1775 he was made one of the sixty members of the “Committee of Observation” and on May first of that year was elected to the “Committee of One Hundred” which superseded the former body and took over the management of local affairs in the city.

When the British forces occupied New York, the Gilberts, along with almost every other supporter of the cause of liberty, prudently left town to preserve their safety and it was seven years before they could return home.

William Gilbert, Silversmith: A pastel portrait by James Sharples. This was probably painted in New York during the last decade of the 18th Century.

Where they lived during that time has not been discovered, but it was presumably either in eastern Connecticut or northern Westchester County, since William Gilbert enrolled in Colonel John Lasher’s regiment of New York militia. His brother-in-law, Ephraim Brasher, also served in this organization and probably both these silversmiths were present with it at the Battle of Long Island. Gilbert rose to the rank of captain, while Brasher became a lieutenant.

The Gilberts seem to have returned to New York as the British went out. Under date of November 26, 1783, which was the day after the redcoats evacuated the city, General Washington was presented with a document entitled: “The Address of the Citizens of New York, who have returned from exile, in behalf of themselves and their suffering Brethren,” in which the Commander-in-Chief was thanked for his services in ridding the city of the English troops and so enabling those patriots who had been forced to flee to return to their homes. Among the signers of this paper were the silversmith, who in this instance signed as William Gilbert Jr., his father, and Ephraim Brasher.

A Footed Silver Salver by Gilbert: This piece bears the Bayard crest, engraved in the center. Originally, it belonged to Nicholas Bayard (1736-1798), who had married Catherine Livingston.

A news item which appeared in the New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy on August 27, 1770, gives the approximate location of Gilbert’s shop prior to the Revolution:

“Tuesday Night last some Villains broke into the shop of Mr. Gilbert, Silver-Smith in the Broad Way, and robbed the same of near two Hundred Pounds in Plate, &c. Diligent Search has been made after the Thieves, but we Have not heard of any discovery being made.”

Another Gilbert Sugar Bowl: Here, the base is circular. Bands of beading are combined with simpler "bright-cut" engraving for the decorative design. Loaned from the collection of Herbert L. Pratt.

Undoubtedly the site was well down Broadway, south of Wall Street, and since Gilbert is listed in the New York City Directory of 1786 as being then on Broadway, it is probable he returned to his old stand after the Revolution for some years at least. Probably, too, as was customary, he resided at the same address. But later, he moved his shop to 26 Dey Street and about the same time he acquired a splendid estate on Greenwich Lane in Greenwich Village, then on the outskirts of town. His land began about a block north of Washington Square and extended nearly to 11th St, while across town it ran from near 5th Ave. almost to 6th Ave.

A Gilbert Cream Pitcher: The shaping of the base, in concaved octagonal form, is unusual. The touch-mark, Gilbert, in script, can be seen on the side of the base.

By 1800, Gilbert had become a prominent and influential citizen. One may picture him being driven to his shop each morning by his coachman behind a handsome span of horses. He had been an Alderman, representing the West Ward, at the formation of the first city government after the evacuation of the British and he continued to be re-elected to that office each year until 1788 when he was chosen as one of the city’s representatives in the State Assembly.

He was also a member of the Assembly in 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793, and from 1803 to 1808. He was Commissioner of Excise for several years, was in charge of the renewal of tavern licenses in 1786, in 1794 became an Associate Justice for New York City. In 1801 he was Assistant Alderman for the Seventh Ward and Alderman for the Eighth Ward in 1804, while in 1803 he was Prison Inspector.

Two Pieces of Flatware by Gilbert: Above, a dessert spoon; below, a ladle. Both are decorated with "bright-cut" engraving. On the spoon it extends the entire length of the handle. The ladle is from the collection of Mrs. Robert B. Noyes.

In 1809 he was elected to the State Senate, an office he held for four years and in his final year as a member of that body was also a member of the Council of Appointment. Thus when he retired at the end of 1812, Gilbert’s public service had extended over a period of thirty years, or nearly forty years, if his pre-Revolutionary and Revolutionary activities are included.

He was also interested in the affairs of his community in other directions besides politics. Thus, for example, in 1791, he became Treasurer of the Museum of the St. Tammany Society, otherwise known as the American Museum, apparently soon after its organization by John Pintard. Of course, too, he was a member of the Gold and Silversmiths’ Society.

Gilbert's Touch-Mark: This one, his surname in script letters, is the one most frequently used. He had three others, but pieces bearing them are rarely found.

When, on December 2, 1784, General Washington arrived in New York for a shot visit, he was received with tremendous enthusiasm by the inhabitants and the City Council voted him the freedom of the city to be presented to him in a gold box. The making of the box was entrusted to Gilbert and it is, of course, the most important piece of work he turned out. The payment warrant was approved by the Council on January 18, 1785, for the sum of 46 pounds 16 shillings to W. W. Gilbert for “A Golden Box to enclose the Freedom presented to his Excellency, General Washington.”

Most of the examples of Gilbert’s work which have been examined seem to date in the period between the close of the Revolution and 1800. During these years the vogue for neoclassical designs, under the influence of the Adam brothers, was most potent. The silversmith made much use of the Grecian urn motif for his hollow ware and in the handling of this graceful form he achieved a notable success.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Albert Einstein’s "Theory of World Peace"

Albert Einstein’s "Theory of World Peace" 'Roadshow' Appraiser Shares How She Assesses Turn-of-the-Century Jewelry

'Roadshow' Appraiser Shares How She Assesses Turn-of-the-Century Jewelry Driven to Drink: How 1930s Booze Labels Helped Americans Forget Their Troubles

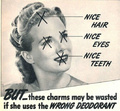

Driven to Drink: How 1930s Booze Labels Helped Americans Forget Their Troubles Selling Shame: 40 Outrageous Vintage Ads Any Woman Would Find Offensive

Selling Shame: 40 Outrageous Vintage Ads Any Woman Would Find Offensive How a Refugee Escaped the Nazis to Become the Father of Video Games

How a Refugee Escaped the Nazis to Become the Father of Video Games Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Hi! I have a William Gilbert bright cut all the way down the handle,same design.At the top it has a ship in full sail with nthe words “Spero melloria”Do you have any information on the William Gilbert spoon,9”. Thank you. Gerard Howell

I inherited a beautiful, working Decatur clock, made in Wiasted County (?) by the Wm. L. Gilbert Clock Co. It doesn’t show up on any of the websites. Any ideas?? Thank you. Beth Jones

I have recently purchased some flatware that I do not think is silver . It has a stamp that is very simalar to the Gilbert stamp. It appears just like the stamp shown above but is broken up to Gil bert .The gil above and off center to the left. Ther are to other stamps that appear to be triangles with a cross or a t on top of the triangle. the gilbert is in the same script or cursive. The handles are bone possibly whale .I don’t think they are ivory the pattern is not correct. There are only forks and knives . If you could give some insight . Thanks and best regrads D.Kim Gross

I have just been given a beautiful mahogany box with knives and forks exactly the same as the D.Kim Gross, the same stamps and bone handles, can you give me any information?

I was fortunate to have obtained at auction a hand-drawn map by the-then City Surveyor Casimer Georck, of the newly laid-out lots belonging to William Gilbert, dated December 16th, 1794. These lots were laid out in lower Manhattan. I found it fascinating that Mr Gilbert named two of the streets after his wife “Cozine (sp)” Street and his family name “Gilbert Street”. The plot was also bordered by “Herring Street” to the East, and land owned by Thomas Ludlow Ogden to the West.