Andrew Hollingsworth, a Chicago dealer of fine Scandinavian furniture and the author of “Danish Modern,” talks about the roots of Danish Modern design, its evolution, some of its best-known practitioners, and the reason why the chair is such of symbol of the aesthetic.

I grew up with antiques, mostly English, and I’ve lived around the world and traveled a lot as well. Art had always been a passion of mine. Then I discovered furniture when I was living in Switzerland. I saw a set of Danish Modern chairs by a designer and architect named Ole Wanscher at a show. That was in the early ’90s before the market for these things really started taking off, before anybody really knew what some of this stuff was. I fell in love with those chairs, and the rest is history.

Today I specialize in Danish Modern furniture from 1930 to 1970, although I also deal in merchandise from Scandinavia as a whole. I acquire most of my furniture overseas because the furniture that was imported into the U.S. tended to be production pieces, sometimes of high quality but production pieces nonetheless. My business mainly focuses on the higher-end cabinetmaker pieces.

Of course, there were Americans during the period who traveled to Europe and returned with pieces of fine furniture, so cabinetmaker examples can be discovered here as well. And some of the big names, like Finn Juhl and Hans Wegner, were exporters, so those pieces are very desirable and sought after.

I always had a dream of being a writer. When I left the banking world, one of the things I explored was writing, but it wasn’t something I actively pursued at the time. I had recently opened a gallery in Chicago and there was a publishing convention in town. My gallery’s PR person had arranged some local press coverage of an exhibition I was having on Børge Mogensen. A publisher came in and basically offered me a book deal. It was just one of those nice coincidences of life.

Of course, I had no idea at the time how involved the project was going to end up being. I didn’t quite grasp the incredible time commitment that the photography would eventually take. I continue to toy with ideas for another book, but I don’t have anything in the works right now.

Collectors Weekly: Who gets the credit for starting Danish Modern?

Hollingsworth: The person who’s considered the grandfather of the style is Kaare Klint, who lived and worked in the early part of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the furniture school at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen in 1924. He was a very charismatic guy, so that’s part of the reason why he gets so much credit, but he also produced very detailed studies about proportions and forms and so forth.

His belief was that form had been perfected throughout history, and that there was no need to reinvent it. He thought that the basic proportions of a chair, for example, had already been refined, and he opposed what some of his European counterparts were trying to do in the Bauhaus movement. Rather than reinventing the chair, he believed we could add modernity to it in terms of line, and then eventually materials, although he was essentially a traditionalist on the materials side of things, too.

Klint influenced a whole school of people that we know from the mid-century, sometimes in direct ways and sometimes in more rebellious ways. Anybody who is anything in the Danish design world was either a follower of the Kaare Klint philosophy or completely rejected it and attempted their own sort of thing, albeit with that sort of Danish understatement and sensibility of clean lines.

Klint’s designs appear very traditional-looking to our modern eye, and some are even a little clunky. That was refined by his successors, Ole Wanscher—whom I admire most—Børge Mogensen, and some others. Poul Kjærholm was another; he worked in steel, marble, glass, and industrial materials.

You also have Arne Jacobsen, who paired industrial processes with organic innovative forms. Some of Jacobsen’s pieces, although very iconic, are the least comfortable to use. That went against one of the tenets of the Kaare Klint school—that design shouldn’t be design just for its own sake but should fulfill the human need for comfort and utility.

Other big names in Danish Modern design are Hans Wegner, Finn Juhl, and Nanna Ditzel, who was one of the few women working during the period. She’s still alive and still designing.

Some studied at the Academy, but other notable designers like Arne Jacobsen didn’t. The interesting thing is that many of them, like Jacobsen, trained to be architects. As a result, their furniture has an architectural quality to it. The result was often entire environments that were modernistic inside and out.

Collectors Weekly: Did the Danish Modern movement parallel the Mid-century Modern movement, or were they pretty separate?

Hollingsworth: They share roots in the 1930s and the Bauhaus, in the steel movement in Holland, and in similar movements in the U.S., but they were ultimately separate.

The period that I consider Danish Modern would be 1930 to 1970, but the real growth in the movement took off in the postwar period. Danish Modernism came about because of all that post-World War II growth and the need to supply goods for an expanding population. It’s remarkable that during the ’40s, when butter and other food supplies were being rationed in America, Denmark was making all these high-end goods. Their industrial base had been left alone because it was too small to scale up for the occupying German war machines.

“The focus of Danish design, the object that had the longest-lasting influence, was the chair.”

I think the main thing that most Americans get confused about is the difference between Danish and Swedish design. Swedish design has much more of an organic and expressive presence, as do the fabrics and colors that were used in Swedish furnishings. The Danish are more severe, very English in a way. By and large, they loved darker woods. Their furniture tended to be pretty austere. The Norwegians, being Norwegians, were in between, but they were probably a little bit closer to the Danes.

Unlike designers in the rest of Europe, they weren’t throwing out historical form, by and large. They still had a love of traditional materials even though there were very big exceptions to that rule. In America—we’ve always been the melting pot—you see the whole range. A lot of our American manufacturers overtly copied Danish design. Even some of the big silverware manufacturers like Gorham had Danish designers that worked with them. When American manufacturers did an outright copy of Danish Modern, they often used Danish designers to make it more authentic.

Collectors Weekly: How was Danish Modern connected to traditional cabinetmaking in Denmark?

Hollingsworth: It came out of the roots of the Kaare Klint school and the big cabinetmakers of the day. To a certain extent, even the production houses in Denmark at the time were relatively small scale. So there was a respect for the importance of quality to all of them.

During that period there were annual cabinetmaker exhibitions. Those shows were the centerpieces of discussion about design and the interrelationship between designers and production houses. Fritz Hansen, for example, was considered more of a cabinetmaker up until the ’50s when he participated in the exhibition. The exhibitions were very important right up to about 1966. Everybody showed up to see the latest new thing. The pieces on view were the iPhones and iPods of their day. It was such a creative period, perhaps never to be repeated.

Collectors Weekly: Besides the modernist movement, what else influenced Danish design?

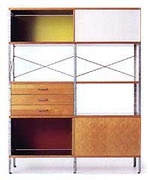

In many cases, Danish Modern furniture put function before form, as seen in this plain, teak cabinet.

Hollingsworth: There were classical 18th-century English influences, as well as classical Chinese influences. Some of the most famous Børge Mogensen designs took their cues from historical Spanish design. The Danes also looked to Greek and Egyptian design—Egypt is where one of the first chairs came from. That’s the thing about being a small country like Denmark: You’re influenced by what’s around you and what’s out there. They embraced that and applied their own sensibility to it.

You don’t look at a Danish Modern design and say, “That’s a copy of an 18th-century such-and-such.” That doesn’t come to mind. They made it their own, and they were so studied about it. I think a lot of designers today aren’t. They don’t necessarily know the history of design. They’re probably interested in it to a certain extent, but things have changed so much in materials and so forth that there isn’t that reverence for the history in a way that there once was.

Collectors Weekly: Are certain designers known for specific innovations or styles?

Hollingsworth: Arne Jacobsen is very much associated with the Ant Chair and organic styles. Finn Juhl is also known for a very organic design sensibility, but he used much more traditional materials. They each had their own kind of interpretation and views on the world and have particular, individualistic looks.

Another important designer was Verner Panton, who was really more ’60s-oriented in terms of the plastics and the wild designs that we think of from that period. He is sort of iconic in that whole ’60s plastic realm.

Collectors Weekly: What were the key materials used in Danish Modern?

Hollingsworth: Teak was the biggest. It’s a lovely wood, yet it has a bad reputation with some folks. It became associated with poor quality, but there are wonderful pieces of craftsmanship in teak. European oak was probably second. I’m not quite sure where rosewood falls into that, but rosewood was always the upgrade. It was the expensive version of anything. In terms of woods, those were the three big ones. And then people like Jacobsen and others also added steel to the mix.

Collectors Weekly: What besides furniture did these designers produce?

Hollingsworth: There are plenty of examples of architecture by those guys, although they are probably not as familiar to Americans since much of that work remained local or stayed within Europe. Arne Jacobsen’s work in Oxford, England, for example, was important, and one of his most famous projects was the Royal SAS Hotel in Copenhagen, which was entirely his design. There’s still a room there that’s completely fitted out in the period. The lobby, too, has been redone in that era.

Cabinetmaker R. Rasmussen made this example of Kaare Klint’s famous Barcelona Chair, which here features mahogany legs and ostrich leather on the seat and back.

But I think the real focus of Danish design, the object that had the longest-lasting influence, was the chair. The cabinet piece was important because designers set in place the foundations for industrial design and large-scale mass production by standardizing the different sizes of cabinets according to usage, but the chair was the fundamental form.

A chair is the hardest thing to design because it’s got to be comfortable even though people are made in all different sizes, shapes, and forms. What’s comfortable to me may not be comfortable to you, but there are some defining proportions that help to determine whether it’s comfortable or not.

The physics of the chair are also important because if you don’t get it right, the thing can collapse on you. In fact Mies van der Rohe once said that designing a chair was much more difficult than designing a skyscraper. That’s got to be somewhat of an exaggeration, but the important thing is it’s a much more technical subject than you or I as novices would realize.

People always ask me, “Why don’t you design furniture? You have such a good eye.” I just don’t feel like I have something really strong and different to say. After all, the Danes were masters of this. True, Arne Jacobsen was really much more about form than he was about comfort, and I think he probably would admit that to a certain extent if he were still around today. But most of the Danish designers really cared about comfort, so it’s rare that you sit in a Danish chair from the period and are uncomfortable. Maybe it’s because I have a Danish body, but for me they’re amazingly comfortable.

Collectors Weekly: What were some of the most notable chair designs associated with the movement?

Hollingsworth: The Ant Chair and the Egg Chair, both by Jacobsen, are at the top of the list. I’m pretty sure the number of Ant Chairs sold is in the millions. There’s the Chieftain Chair by Finn Juhl that the Japanese, in particular, love. They have singlehandedly driven up the price of those chairs. And Hans Wegner made the Wishbone Chair, which had a Y shape, and the Round Chair, which some people call simply The Chair.

Another would be the Barcelona Chair from 1930, designed by Kaare Klint. It happened to have the same name as Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair because the two men exhibited at the same show in Barcelona. Both won an award for design even though they’re very different pieces—Klint’s is a dining chair, van der Rohe’s is more of an easy chair. I think most people would agree that the Mies version was not so successful in terms of comfort. It is more suited to the lobby of a building, where it makes a strong design statement, than as something you’d want to sit on for very long.

An interesting aside about the Bauhaus movement in particular, and the field in general, is that they had this idealistic view of the common man and industrial processes. The reality was that many of their designs were very high end and very expensive. For example, the Mies van der Rohe Barcelona Chair was always very expensive. So the Bauhaus designers weren’t quite as successful as they wanted to be about reinventing design in a way that the world could afford.

Collectors Weekly: How did the designers balance comfort with aesthetics?

Hollingsworth: Klint believed that the comfort or utility of a piece defined the form, and that you approached it in that order: If you first made sure that a piece of furniture was comfortable, its form would arise from that.

As a result, most Danish Modern furniture is unembellished. That’s why it appeals to people who like things pure and simple, and why it doesn’t appeal to those who like things much more ornate. There is just a rawness to the form itself. That’s what I find beauty in, but other people have different views, obviously. It goes back to Klint’s concept that the form had been perfected throughout the centuries, so there were already classic shapes that appealed to most people. I think that’s still true today.

Collectors Weekly: Who bought Danish Modern? Was it accessible to the middle class?

Hollingsworth: That’s still a subject of some contention today in Denmark, especially when you talk to curators at the museums. They’re dismissive of the designers who were only producing pieces for the high end of the market. They really don’t have much regard for them, and I think that’s a mistake.

There’s a famous quote in my book about how people didn’t just like the furniture because they were being fooled by people with blond hair and blue eyes; they liked it because they were snobs and it appealed to their sense of elitism, or so goes the quote. Indeed, the work of the designers that I focus on tended to make things for the wealthy. However, as the movement evolved, Danish Modern furniture was designed mainly for the middle classes.

The postwar era ushered in suburban expansion and the growth of families. Being modern during that period was a good thing, and people wanted to embrace all that technology had to offer. The furniture was very solid, well made, and family-friendly. That’s why I’m always a little amused when people consider it “adult” furniture. It was always designed to live among people, to fit in with everything that was going on in a household.

Collectors Weekly: You said 1970 was the end of the period. What happened around that time?

Hollingsworth: As with anything, competition came into play. Much of the competition was cheap—in this country especially, we know how to make things efficiently or to outsource them. The other thing that happened was that the design as a movement was coming to a natural end. Technology was changing the focus because you had these new plastics, the colorful ’60s and ’70s sort of furniture.

So stylistically things were changing and were less conservative. The baby boomers were coming of age and had their own design philosophy and way of looking at the world. Their aesthetic was even less traditional than some of the mid-century designs that were available.

Also, raw material prices had gone up. Rosewood, for example, was pretty much deforested, so other materials were substituted. At the same time, the quality of goods was declining because everything was all about cost. It was no longer about the originality and innovativeness of the design and the processes. So it just came to a natural end for a multitude of reasons.

The style was totally neglected in the ’70s and ’80s. Then, in the 1990s, folks started rediscovering it. I’m always surprised at the reactions that different people have to it. People of the generation that grew up with it can sometimes have a really negative reaction like, “God, that stuff.” For others, though, it’s like reliving their childhood—they get very excited about it. Oftentimes they still have some pieces in their homes from the period.

People of my generation and later, we look at it from a very different lens because we don’t necessarily have these memories associated with that period. I just find that whole ’40s and ’50s era to be classic.

Collectors Weekly: What trends have you noticed among contemporary collectors?

Hollingsworth: People are becoming more and more selective because they’re more knowledgeable. Ten or 15 years ago, you could pick up almost anything cheaply, but that’s changed. Who’s buying, how they’re buying, and what their expectations are has shifted. Premiums are placed on the work of well-known designers, especially when the material is unique. There’s an increased professionalism in terms of the market.

Mahogany and ostrich leather give this Ole Wanscher chair, produced by cabinetmaker A.J. Iversen, its casual-yet-refined appearance.

That said, the everyday design pieces are much more affordable than they used to be just a few years ago. There are some wonderful buys out there in terms of cabinetmakers who are not well known but who did tremendous work during that time. People who really love design and quality but are not so focused on a famous name have great buying ability because there’s less competition.

Interestingly, most of my clients are not in the collector category at all. They’re people who like furniture but who are really seeking comfort, as well as something special, something different. They don’t necessarily want to have houses full of Danish Modern. Nowadays, eclecticism is big and purity is not necessarily as important as it once was.

Collectors Weekly: Has your taste changed from the time you discovered Danish Modern furniture?

Hollingsworth: I guess I’ve become more of a purist simply because I found what I love. That very first set of dining chairs that I bought was, and still is, the one that is nearest and dearest to what I love about Danish Modern design. Certainly my understanding of the field has broadened my appreciation for diversity. That has also evolved.

As I said, I grew up in a household with English antiques, and my mother also had a fondness for anything with a Chinese influence. The pieces that I love the most have that classical Chinese influence and often also have English inputs. So my taste has remained remarkably consistent. I’ve always focused on purity of line, cleanliness of design, and simplicity. That’s kind of pervasive to my whole personality.

I like things simple. I keep waiting to fall in love with the Rococo period, or something, but it hasn’t happened. I guess that’s just not who I am. I appreciate it for what it is, but I could never fill my house with that.

(All images in this article courtesy of Andrew Hollingsworth and photographed by Scott Thompson Photography)

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Eames, Nelson, and the Mid-Century Modern Aesthetic

Eames, Nelson, and the Mid-Century Modern Aesthetic Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs

Mid-Century Modern Furniture, from Marshmallow Sofas to Hans Wegner Chairs Danish Modern FurnitureDanish Modern tables and chairs, desks and dressers, and other types of fur…

Danish Modern FurnitureDanish Modern tables and chairs, desks and dressers, and other types of fur… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fascinating! Andrew is extremely knowledgeable.

I have a modern Swed dining table, signed by Karl – Erik Ekselius by JOC. It’s in excellent condition and unique as the legs resemble three toed birds feet back to back, which spread apart as leafs are added (two leafs included). The table is accompanied by 4′ Moreddi elegant swayed back dining chairs.

Wondering what the value may be?

Hello,

My father has Arne Jacobsen chairs. 2 Carver and 4 Diners, they are in teak with a twine seating. They are stamped underneath and are in immacultate condition. My father was a cabinet maker and worked hard to purchase these chairs, he knew what he was buying and they have had pride and place in his dining room since 1970. Are you interested in them?

We have photographes if needed.

I put a table on awhle back .I was surprised that know one had any information on it. antique? 2leafs and can be raised to hieght of 29 1/2 ins and down to 17 1/2 ins . This can be done because of springs under apron and henges on the legs that fold down onto each other. (I think that’s the right term.) NO marking but has beading around top and down both sides of legs. No drawers very plain but different from anything I’ll seen.

I am trying to find out if a chair that I have is a Jan Ekselius chair from the 1970-1979 period. Are there identifying marks? Where would I find them?

Dear CW,

We have a modern,teak wall unit from the 70s Midcentury danish/ scandinavian collection.

It holds a writing desk , locked compartment to which the key has broken,

We cannot find a place in or on the unit who tells us who the maker oft his lovely piece is, that we

have enjoyed for so long.

Can you give a Senior a helping, guiding hand to find a key or even the whole lock and key to it?

Respectfully and most grateful for your help,

geolis1958