Bob Seidemann leans on his cane and squints at one of his black-and-white photographs. His white hair, beard, and matching eyeglass frames give him the appearance of an aging hippie saint, or perhaps its friendly ghost. The print he’s scrutinizing lies on a table with dozens of others from a portfolio called “The Airplane as Art,” which, in recent years, has brought high-altitude prices at auction—all but one of the images in this article are from that portfolio, and most are being reproduced online for the very first time. In this particular print, a man named Robert Sandusky stands stiffly in a dark suit and striped tie on a desert airstrip. Behind him looms a single-passenger fighter jet nicknamed the Black Widow II, one of only two prototypes of Northrup’s YF-23 Advanced Tactical Fighter, for which Sandusky was the chief designer.

“I thought that if the airplanes were art, then the people that make them are artists.”

When Seidemann took this photograph on February 28, 1991, he was well into his third decade as a professional freelance photographer, having shot everything from album covers for Eric Clapton to portraits of David Lynch for “Esquire” magazine. For his part, Sandusky and his employer, Northrup, were in a fierce battle with Lockheed, both of which had spent the last four years and almost $700 million each in taxpayer money to prove they would be the best defense contractor to build the next generation of fighter jets for the Air Force. The YF-23 was stealthier and marginally faster than its Lockheed counterpart (it could reach Mach 2, or double the speed of sound), and many praised its badass, death-from-above design. But within a few months of Seidemann’s desert rendezvous with Sandusky, Lockheed would win the lucrative Air Force contract, eventually producing almost 200 F-22 Raptors, as its final design was called, and reaping more than $66 billion in revenue until production of the twin-engine fighter ceased in 2011.

Naturally, given the incredible tale of technological achievement, Defense Department politics, high-stakes finance, and aviation wizardry lurking in this innocent photograph of a slightly husky guy standing next to an airplane, I ask Seidemann about the weather.

The tail of a 747, photographed outside the Boeing factory in Everett, Washington, 1991.

I really don’t know what’s come over me—nerves, I guess. After all, “The Airplane as Art” is also pretty badass, both in scope and reputation. Its 302 photographs taken between 1985 and 2000 were culled from thousands of images of commercial and military airplanes, along with many of their chief engineers, designers, and pilots. Seidemann hand-enlarged each print himself, enough to produce 20 boxed sets (that’s more than 6,000 prints, for those of you keeping score). Ten of those sets feature the signatures of 75 of their subjects, Sandusky included, and, of course, the photographer also signed them all. Boeing owns one of the coveted double-signed boxed sets, as does the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the last two portfolios that sold at Sotheby’s fetched more than $200,000 apiece.

I know all this, but I’ve noticed that the tarmac at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert, where the Sandusky photograph was taken, is wet. Did Seidemann hose the surface down, I ask with as much solemnity as I can muster, or had it just rained?

The photographer blinks. “It had rained,” he says softly, and then proceeds to explain the reason why Sandusky is smiling in a second shot, in which he’s shaking hands with Seidemann, who had set the timer on his Hasselblad Super Wide camera to pull off the trick.

“He was laughing his ass off,” Seidemann remembers. Turns out that even though Sandusky was the YF-23’s designer, no one had ever taxied one of these planes out of its hangar for him. What kind of pull, Sandusky must have wondered, did this wavy-haired photographer with the thick New York accent have that he didn’t?

Photographer Bob Seidemann (left) shakes hands with Robert Sandusky, chief designer of the Northrup YF-23 behind them, Edwards Air Force Base, 1991.

In fact, by 1991, Seidemann, who grew up in New York but has lived most of his life in California, was a familiar face at Edwards and its Navy counterpart to the north, China Lake Naval Weapons Station—he probably knew the guys in charge of moving the YF-23 from Point A to Point B better than Sandusky did. But Seidemann’s love of airplanes and reverence for the men who designed and flew them (very few women are members of this exclusive club) began long before an endeavor as monumental as “The Airplane as Art” was so much as a glimmer in his eye. Airplanes may not have been the photographer’s subject during his career, but they were always his passion.

“I had gone to the Manhattan High School of Aviation Trades,” Seidemann tells me during one of our many meetings last summer and fall. “It was a trade school for people who wanted to become aircraft mechanics or engineers. I just loved airplanes—the machine, the idea of the machine, how it worked, why it worked, and what the machine has meant to the world.”

Lest you get the sense that Seidemann’s interest in aircraft is purely academic, he readily admits to being something of an airplane fanboy, the sort of kid who would have been right at home lying on the hood of Garth’s AMC Pacer in “Wayne’s World” to watch planes come in low for a landing at Aurora Municipal Airport. “I lived near LaGuardia Airport,” Seidemann told a television interviewer in 2001. “As a teenager, I enjoyed seeing airplanes landing. I used to marvel as they would fly by.”

F-86 wreck with skull, China Lake Naval Weapons Station, 1987.

That was back in the late 1950s, which means almost 30 years passed before Seidemann would begin work on “The Airplane as Art.” In the intervening years, the technology of cameras rather than airplanes commanded his attention. While still living in New York, Seidemann learned how to take pictures from a dance-photographer named Tom Caravaglia, and his career behind a lens blossomed in San Francisco, where he was drawn to the city’s psychedelic music scene. In particular, he got tight with the members of Big Brother and the Holding Company, with whom he lived for a while in nearby Marin County, and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, for whom he designed the cover of the incomparable guitarist’s first solo album. By the late 1960s, Seidemann was famous—in some circles, infamous—as a rock photographer, a career that both derailed and incubated his interest in airplanes.

“To be honest with you, I wasn’t very interested in the music,” he admits today. “It was the scene, you know? I didn’t intend to become a documentarian; I was just hanging out, a friend of these people. I had a little bit of skill with the camera, able to do stuff that did not require a lot of expertise. As their work progressed, so did mine.”

Mariora Goschen at age 11, holding an airplane-like spaceship. Seidemann titled this photograph “Blind Faith,” which Eric Clapton used for the name of his new band.

His progression as a photographer included surreal “head-shop” posters of the Grateful Dead (“They were a real pain in the ass to work with.”), two portraits, including a nude, of Janis Joplin (“She wanted to be a sexpot.”), and a collaboration with acclaimed rock-poster artist Rick Griffin (“He died about 500 years too soon.”).

And then, in 1969, Seidemann shot a photograph he titled “Blind Faith,” which Eric Clapton used as the name of his post-Cream super-group, as well as for the cover of the band’s only album. Notoriously, it featured a nude 11-year-old girl named Mariora Goschen (whose parents had given permission for the shoot) holding an airplane-like spaceship made by a London jeweler named Mick Milligan.

Record retailers in the United States promptly freaked out. It was not just Goschen’s nakedness; they were convinced that the object in her hand was blatantly and deliberately phallic, spurring a new cover featuring a more traditional portrait of the band for the album’s U.S. release. But Seidemann never intended the imagery to be titillating: “To symbolize the achievement of human creativity and its expression through technology,” he later wrote, “a spaceship was the material object. To carry this new spore into the universe, innocence would be the ideal bearer, a young girl, a girl as young as Shakespeare’s Juliet. The spaceship would be the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the girl, the fruit of the tree of life.”

“Blind Faith,” Seidemann told me recently, was chosen as the title of the photograph because “that’s what she represented.” At last check, the original album cover was a collector’s item, and a Seidemann print of the image is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

A pair of SR-71 reconnaissance jets parked at the Lockheed facility in Palmdale, California, 1998.

For the next decade or so, Seidemann leveraged his connections in the music industry to become one of the most respected rock photographers of his generation. In addition to his work for Jerry Garcia and Blind Faith, he created covers for Jackson Browne and Neil Young. But Seidemann was never comfortable in the music racket, which author Hunter S. Thompson once described as “a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs.” There’s little doubt Seidemann shared these sentiments.

“I was working in the music business,” Seidemann says today, “and I often thought, ‘what a low-life crowd this music industry is.’ I wanted to find something to do that I could be really proud of.”

That’s when, in the mid-1980s, he returned to his love of airplanes for inspiration. In an early description of “The Airplane as Art,” Seidemann laid out his motivation: “The concept for this work sprang from the notion that the airplane is a quintessential manifestation of our humanness, tool making. They are an ancient, primal dream made real, to fly. The essence of the original desire to fly was, I believe, aesthetic. All subsequent uses of flying machines are byproducts. I look upon the machines themselves as objects of art, a result of the creative process.”

B-52 hulks on the desert floor, Edwards Air Force Base, 1988.

As luck would have it, there were plenty of these machines lying around—literally—not too far from where he was living at the time in Southern California. “A man out at Planes of Fame in Chino, east of L.A., gave me a tip,” Seidemann recalls of a visit to a popular aviation museum. “He said there were some wrecks out in the desert, and if I could only get the Navy to let me go out there, I would have some great photo opportunities.”

That’s how Seidemann learned about the China Lake Naval Weapons Center, which is more than a million acres of nothing out in the middle of nowhere, roughly halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. Beginning in 1985, Seidemann made dozens of trips to this isolated area, as well as nearby Edwards Air Force Base, to photograph the ruined hulks of multimillion-dollar fighter jets and lesser flying machines, all of which had been left to bake in the mercilessly hot desert sun.

“That was a wonderful place to work,” he says today, without a trace of irony (Seidemann’s cane indicates those days are behind him). “They use the hulks for target practice. They don’t shoot at them, but they use them for siting, to test their targeting systems. You gotta do it somewhere,” he adds. “You can’t do that sort of thing in downtown New York City or Brooklyn.”

Hulk of a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star at Edwards Air Force Base, 1999.

Eventually, Seidemann got to know some of the sentinels whose duty it was to protect this kingdom of cast-off aviation history. “One of the guys out there gave me a key to the fucking base,” he says, chuckling quietly at this innocent example of pre-9/11 access that would presumably be impossible today. “He said, ‘If you can get here at 3 o’clock in the morning, I’ll leave a key with a guy who’ll take you out onto the field and leave you there. Just don’t make a mess, and don’t screw anything up.’ I spent many days out there photographing those hulks, those wrecks.”

If the colophon that accompanies “The Airplane as Art” is any indication, 1987 was an especially fruitful year at China Lake for Seidemann. More than two-dozen prints in the portfolio were shot there in that year alone, with many of the images of Boeing C-97 Stratofreighters, Grumman Panthers, Douglas A-4s, and Republic F-84Fs taken on trips in the months of July, September, and December.

The “stricken aircraft,” as Seidemann calls them, in the desert proved terrific fodder for the photographer’s camera. Some were so crumpled and deformed, they looked more like abstract sculptures hurled into a landscape painting than the remains of flying machines. Indeed, in “The Airplane as Art,” Seidemann often juxtaposes these beaten forms against their magnificent backdrop, whether it’s a high-desert mountain range peeking through the blown-out window of a cockpit, or the way the desert’s meager vegetation appears to be slowly encroaching on the battered piles of steel lying in their midst.

Tex Johnson, former chief test pilot for Boeing, in the cockpit of the original Boeing 707 prototype, 1991. Johnson is famous for barrel-rolling this plane during a demonstration flight.

Still, if “The Airplane as Art” was only filled with such images, however artfully composed and brilliantly lit, something would be missing. Which is why Seidemann began to augment his documentation of these magnificent machines with their human analogs—the engineers, designers, and test pilots who figured out how to get them into the air in the first place, and then control them once aloft. “I thought that if the airplanes were art,” Seidemann wrote, “then the people that make them are artists. So I began pursuing the creators.”

The trick, of course, was figuring out how to meet these aviation artists, whose brains contained some of the nation’s most closely guarded aeronautical secrets. “You don’t just walk onto Rockwell International’s experimental jet plane site to have a few beers,” Seidemann says. “They’ll shoot ya. So I asked myself, ‘How can I get into situations where I could talk with these mind-bogglingly smart people?’ As he had done in San Francisco’s 1960s music scene, Seidemann decided to become a participating member of the community—a sincere contributor to the scene, whose interests would be taken seriously.

“For $20 or something like that, I joined the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics,” he recalls. “I would get these flyers in the mail, announcing when the next meeting was being held, what they were doing, all that aviation stuff. It was way over my head, if you’ll pardon the pun.”

It was at one of those AIAA meetings that Seidemann met Walter Spivak, who would become the first human photographed for “The Airplane as Art.”

Walter Spivak, the first designer Seidemann photographed, is shown here in 1988 at the Rockwell facility in Palmdale, California, with his B-1B bomber.

“Spivak had been the chief engineer of the XB-70 Valkyrie in the 1960s,” Seidemann says, “and he was the designer of the Rockwell B-1B, which could fly 700 or 800 miles an hour at about 200 feet of altitude. When the meeting broke for lunch, I introduced myself and said, ‘If I can get an airplane to put in the background behind you, would you allow me to take your picture?’ He said, ‘Sure,’ so I went to Rockwell and said, ‘Mr. Spivak says he’ll pose for a photograph if you’ll put a plane on the runway.’ And they said, ‘Anything for Walter Spivak; whatever he wants, he gets.’ So I called Mr. Spivak and eventually photographed him in front of a B-1B. He told me who to call next, and before you know it, I had a big stack of photographs of these people and their machines.”

Seidemann’s second portrait was of a pilot, General James H. Doolittle, who was a lieutenant colonel in the Army when he led a group of fellow pilots, all flying B-25s, on the first bombing runs of Tokyo, Yokohama, and several other Japanese cities during World War II. Coming just three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Doolittle Raid, as it became known, was a serious morale boost for Americans, while it had the opposite effect on the Japanese, whose government had promised its citizens that the island nation would never suffer an air attack. Doolittle received the Medal of Honor from President Roosevelt for his heroism and leadership, and before the war was over, Spencer Tracy would play the flyer in the film “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.” Still, in spite of the acclaim Doolittle had once enjoyed, by July 20, 1988, when Seidemann visited the general at his home in Carmel Valley, California, to take his picture, most people had never heard of the guy.

General James Doolittle, who led the Doolittle Raid over Tokyo and other Japanese cities within months of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Photographed at his home in Carmel Valley, California, 1988.

“He was real happy that somebody was photographing him for the first time in almost 50 years,” Seidemann recalls. “He was a fun person to be around, but I was so nervous. He is probably one of the most important people I photographed, ever.”

“I wanted to find something to do that I could be really proud of.”

For the Spivak shot, Seidemann had placed the airplane designer at a table draped with the architectural plans for the B-1B, on top of which sat an official Rockwell International model of the plane itself. For the Doolittle shot, Seidemann kept the table as a prop, but Doolittle had told the photographer over the phone that he, too, had a model of his most famous plane (the B-25), and that, in fact, he was something of an airplane-model enthusiast.

That got Seidemann thinking, and by the time he arrived in Carmel Valley, a composition for the final shot was taking shape in his mind. Doolittle’s table would eventually be covered by a map of the Pacific Ocean, from the Hawaiian Islands in the east to Japan in the west. Naturally, one of Doolittle’s B-25 models would be placed on top of the map, but Seidemann also rigged a spotlight to shine down on the map just south of Japan’s coastline, and he hung a second B-25 model between the light source and the map so that a shadow of the plane would be visible on the map.

“It was a lot of work,” Seidemann says, “everything I did took a lot of work. But it was worth it. This guy, he’s like one of the eight wonders of the world. I know who he is, but to this day, most people don’t.” (In case that describes you, here’s a link to the Doolittle Raid page on Wikipedia. You’re welcome.)

Arthur Raymond designed the DC-3 for Douglas Aircraft Company in the 1930s, making commercial airflight viable. Photographed in Long Beach with a DC-2, which he also designed, 1989.

Over the next dozen years, Seidemann would shoot the portraits of more than 100 other aviation pioneers and pilots, from commercial designers such as Arthur Raymond (his DC-3 made the airline business viable in the 1930s) and Joseph Sutter (he’s considered the “father” of the Boeing 747) to military specialists like George Schairer (he championed the use of the “swept-back” rather than straight wing design) and Ben Rich (from the U-2 to the F-117A, he was one of Lockheed’s stealth-technology gurus).

Nor did Seidemann stick exclusively to Americans, although the majority of the portfolio does. In one portrait, taken at Planes of Fame on May 19, 1990, we see Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s best known World War II fighter pilots, posing before the only airworthy Mitsubishi Zero in North America.

“He’s the last surviving member of a very hot team of samurai warriors,” Seidemann says. “You didn’t get to pilot one of those airplanes unless you were a samurai. He said to me, in Japanese, ‘You know how samurais look in the movies?’ That’s what he wanted. And he said, ‘I’m doing this for you because I understand that in your heart you know what these machines were about.’ It’s the machine they all love,” Seidemann adds, referring to the thing that connects all pilots, designers, and aircraft engineers to each other, regardless of nationality. “That’s why he allowed me to take his picture. The machines become the bond between former enemies.”

Saburo Sakai flew Mitsubishi Zeros for Japan during World War II. Photographed at Planes of Fame in front of the only airworthy Zero in North America, 1990.

Like this Sakai anecdote, every picture in “The Airplane as Art” tells a story, but some of Seidemann’s airplane tales are downright epic. Take the yarn behind the smiling visage of General Vladimir Ilyushin, whose wide-crowned hat and shit-eating grin appear to be echoed in the features of the all-titanium Sukhoi SU-100 intercontinental nuclear-bomber prototype that’s parked behind him and to his left. As the chief test pilot for his family’s Sukhoi Design Bureau, Ilyushin is the only person to have flown that plane, which was built to cruise at better than Mach 3. And if you are beginning to suspect that Seidemann did not take this particular photo at Edwards Air Force Base, China Lake, or any other air facility in the United States of America, you’d be correct.

In fact, the two men were in Russia, about 15 miles south of Moscow, and very drunk.

“I’m in London for the 1990 Farnborough International Airshow,” Seidemann begins, “and a group of Germans have just backed away from my request to photograph a World War II-era Messerschmitt. They have paid my airfare and hotel, but it means I’m stuck in London for a couple of weeks, carrying all these bags and equipment around like a mule. Fortunately, I have some friends I used to stay with in the ’60s, so I call them up and hang out with them for a bit.

General Vladimir Ilyushin is the only man to have flown the intercontinental nuclear bomber prototype behind him. Photographed at the Russian Air Force Museum, south of Moscow, 1990.

“One day,” Seidemann continues, “I decide to go to the British Museum to see the mummies, stuff like that. I take the Tube to the museum, but when I get out of the subway, I’m in the middle of London, and I don’t know where the hell I am. As I’m looking around the neighborhood, I notice this guy in a gray suit standing in front of a movie theater. I walk over to him and say, ‘Pardon me, but do you know the name of this square?’ And he says in a thick accent, ‘No, I don’t.’ And I say, ‘You have an interesting accent.’ He says, ‘I am from Moscow,’ and I say, ‘I will be traveling to Moscow to photograph Genrikh Novozhilov.’ And he says, ‘Novozhilov! I know him well. He worked for my father. I am Vladimir Ilyushin of the Ilyushin Design Bureau.’”

The Ilyushin Design Bureau was founded by Vladimir’s father and is one of the leading aircraft manufacturers in Russia. Turns out Vladimir was also in town for the Farnborough Airshow.

After cooling his heels in London, Seidemann kept his date with Novozhilov, and also met up with his newfound friend, Vladimir. “Ilyushin and his wife pick me up in a 50-passenger red tourist bus,” Seidemann recalls, “just a huge fucking bus, to take me out to the old Design Bureau, which is now a museum. Now the thing about Russians is, if you don’t want to get smashed, don’t bother going because they’re going to insist that you get drunk. The vodka bottles don’t have twist caps because you’re expected to drink it all.

“Anyway, we get out there, and for some reason, they won’t let us into the museum. So Ilyushin has to pull some strings. He goes inside, and I can hear crashing, smashing, chairs flying, suits being torn, it’s like a cartoon. ‘I’m a general, you asshole!’ Bang, crash, bang, bang, bang! And then he comes out, and everything’s all okay; we can go in now.” Even though the Berlin Wall had fallen the previous year, not everyone in Russia had gotten the memo. In the end, more than half a dozen photographs from that September 1990 trip made it into “The Airplane as Art,” thanks to the Russian’s general’s persistence on behalf of the kid from New York.

Time-exposure photograph of a Grumann F-14 taking off from the deck of the USS Nimitz, off the coast of San Diego, 1988.

At some point, Seidemann also decided that it wouldn’t be enough to shoot planes as wrecks, backdrops for their designers, or even as abstract compositions, however compelling all three of those approaches might be. He also wanted to see these machines in action, if possible from inside a cockpit or two. That led to a number of flights in Canadair CT-114 Tutors with the Snowbirds (Canada’s answer to the Blue Angels); several trips in a McDonnell Douglas KC-10 Extender (used to refuel other planes in mid-air); a flight over the South Pacific aboard a C-130 cargo plane; and even a couple of days on the USS Nimitz aircraft carrier, where he shot photos of Grumman F-14 fighters taking off and landing.

Meanwhile, Boeing was giving Seidemann unprecedented access to its people and facilities. “The Boeing airplane company was extraordinarily generous,” Seidemann says in that same 2001 television interview. “They gave me complete access to all of their personnel and every part of their factory. I’ve documented virtually all of their engineers.”

That’s why Seidemann was able to photograph the 747’s chief designer, Joseph Sutter, inside the Boeing 747 factory in Everett, Washington, where the plane has been built since 1968. Seidemann has a natural flair for photographing people (“Esquire” magazine didn’t keep him busy for years for nothing), but Seidemann’s Boeing-factory photographs are often more impressive when the people get out of the way.

Joseph Sutter, father of the 747, at the 747 factory in Everett, Washington, 1991.

Take his shots of 747 tail sections. In one photograph, the picture frame is almost entirely filled with a fat section of rounded gray metal, reinforced by row upon row of round-headed rivets, which you want to reach out and touch. In another picture, the camera is farther away from its subject, allowing the viewer to enjoy the full tail’s vertical and horizontal geometry, which alternately aligns with and bisects that of the factory itself—from the trusses that hold up the enormous building’s roof to the wheeled stairways and stationary ladders that reach into an under-construction 747’s yawning hatches and holds. In a third shot taken outside the plant, we see only the very end of the tail, its surface now bone white against what we assume is a blue sky that reads dark gray in Seidemann’s world of black-and-white. The photograph feels strangely organic, even with the horizontal stabilizer that chops into our field of vision from above, as if hurled like a sheet-metal lightning bolt by a mischievous aviation god.

Back out in the desert, Seidemann let his Hasselblad Super Wide linger on many other examples of Boeing aircraft, all of which have seen better days. Foremost among these is a shot taken from inside the cockpit of a decrepit Boeing Stratofreighter. These planes were built toward the end of World War II and were first put to use during the Berlin Airlift of 1948, before becoming workhorses of the Korean and Vietnam wars. Seidemann is inside the plane’s cockpit to capture the arrangement of its trademark grid of small rectangular windows, which follow the curves of the plane’s oddly domed nose. Off in the distance, visible through those windows, is yet another ridge of desert mountains—perhaps the ones to the east that separate China Lake from Death Valley, perhaps not. One imagines that a group of drunken pilots must have taken this particular Stratofreighter out for a weekend joyride before abandoning the once-proud aircraft in the Mojave, where they left it to cook in the sun and rot.

Boeing Stratofreighter cockpit, China Lake Naval Weapons Station, 1987.

These are the sorts of reveries Seidemann’s pictures prompt—yes they have their own stories to tell, but they can also be armatures for our own flights of fancy. Still, even out at China Lake and Edwards, Seidemann composed his images carefully, lavishing as much attention on the angle he chose to shoot the hulk of a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star lying forlornly amid some desert scrub as he did on General Doolittle and his model B-25s. Behind the broken nose of the Shooting Star, for example, a Joshua tree stands silently in the distance—it was here long before this airplane was dumped in this spot, and will likely be here long after. Similarly, in a photograph of the crumpled, bloated-looking fuselage of an F-86 Sabre, an animal skull has been positioned near the plane’s mangled tail. Since this is a Seidemann photograph, the skull is visible in, but not the focus of, the composition.

And then there’s the Convair B-58 Hustler he shot out at Edwards, which appears to be resting on its landing gear, causing the metal bands that once held four General Electric engines in place to cast dark shadows on the desert floor. The engines were obviously worth harvesting, otherwise their housings would be filled with them yet, but their absence has created those very handsome shadows, which fall at roughly mirror angles to the lines created by the edge of the plane’s wing and the Hustler’s pointed nose.

Convair B-58 Hustler hulk at Edwards Air Force Base, 1988.

Seidemann leans in on his cane again as I tell him what I’m seeing. “I love those two lines converging here,” he says, pointing to the dead-level horizon line I have failed to notice but is now obviously visible at the left edge of the picture, as well as through the empty engine housings I’ve been staring at so intently. These are the sorts of lines, Seidemann suggests, that Tom Caravaglia taught him to look for all those years ago in New York, before he ever imagined he would one day earn his keep taking pictures of people like Janis Joplin or Jimmy Doolittle.

I mumble something about how dumb it must seem to him that I had not noticed the horizon line until he had pointed it out. But Seidemann just looks at me through those white eyeglass frames of his, a twinkle in his eyes. “That’s the arty part, the stuff they pay me the big money for,” he says with a gentle smile. That’s the stuff, one might add, a photographer could feel proud of.

(All photographs copyright Bob Seidemann. To learn more about the artist’s work, visit bobseidemann.com. To see more examples from the portfolio, visit the Getty Museum.)

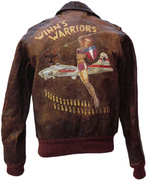

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

Laika and Her Comrades: The Soviet Space Dogs Who Took Giant Leaps for Mankind

Laika and Her Comrades: The Soviet Space Dogs Who Took Giant Leaps for Mankind WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Paper Dresses and Psychedelic Catsuits: When Airline Fashion Was Flying High

Paper Dresses and Psychedelic Catsuits: When Airline Fashion Was Flying High Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa…

Aviation MemorabiliaFrom the start of regular U.S. passenger service in 1914, travelers have sa… Model AirplanesThough toy planes might seem like a byproduct of human flight, toys were ac…

Model AirplanesThough toy planes might seem like a byproduct of human flight, toys were ac… Art PhotographyIt shouldn’t be a surprise that photography became a vehicle for art and op…

Art PhotographyIt shouldn’t be a surprise that photography became a vehicle for art and op… Military and WartimeMilitary and wartime antiques and memorabilia include an enormously wide va…

Military and WartimeMilitary and wartime antiques and memorabilia include an enormously wide va… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Did I miss it or did the article not mention Kelly Johnson at all? I see the SR-71 pictures though.

Bob’s work is absolutely stunning. His eye and camera create fantastic images that expand the imagination. He’s the best.

The author describes the hulks as “steel” when obviously they are aluminum. You would think a journalist would get that right.

The photo of Walt Spivak is taken with B1-B bomber, not a B1-B fighter. Fixed, thanks! -Eds

I HAPPEN TO BE LUCKY ENOUGH TO OWN SOME OF BOB SEIDEMAN’S WORK AND CONSIDER IT THE VERY BEST. HIS PORTFOLIO “AIRPLANE AS ART” IS WELL WORTH THE INVESTMENT.

My I use your picture of Walter Spivak on my blog post?

https://www.russoldradios.com/blog/1929-northland-console-with-shortwave

Your readers might also be interested.

Russ