Despite the ever-widening wealth gap, most of us continue to grasp at the American Dream, which promises financial security in exchange for hard work. In fact, for many workers in today’s economy, attaining middle-class status is exactly that—a dream—while digital technologies have pushed enormous numbers of steady-paycheck employees into the unpredictable “gig economy,” where contracts are the norm.

“If you broke the Hobo Code of Ethics, you would be punished by other hoboes.”

Roughly 140 years ago, American workers faced a different set of economic uncertainties, as machines began to replace able-bodied men in factories and on farms. But back then, a safety net existed in the form of the newly laid railroad, which promised hope to workers willing to trade the comforts of hearth and home for a chance at gainful employment. All one had to do was hop a train to a new town and declare himself a hobo.

The first and foremost thing to understand about hoboes is that hoboes are not bums. Got that? Hoboes are not bums. Hoboes fully embrace the Protestant work ethic, bouncing from place to place, looking for short-term jobs to earn their keep, while bums and tramps want to just bum everything—money, food, or cigarettes. But free-loading tramps and hard-working hoboes have one thing in common: Both have traveled the rails, starting in the 19th century, much to the chagrin of the railroad owners. So-called bums, who might be too old, disabled, or ill to work, tend to stay in one place.

Today, the word “hobo” tends to call up one of two caricatures deeply ingrained in our collective imagination: One is a sad sack with saggy pants, five-o’-clock shadow, and a bindle stick, probably passed out in some alley with a bottle of whiskey—an image that’s interchangeable with that of a bum. The other is a fantasy about living free on the fringes society: jumping boxcars despite the danger, wandering from town to town with no roots or commitments, sleeping under the stars with fellow hoboes who trade banjo tunes and wild stories. Woody Guthrie, Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, James Michener, Louis L’Amour, Clark Gable, and multi-millionaire Winthrop Rockefeller were all drawn to this untethered lifestyle and told stories about their time on the rails, burnishing the legend.

Top: Lightweight boxer Lou Ambers mounts the ladder of a train car with a large bag over his shoulder in 1935. (Photo by Alan Fisher, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress) Above: Three tramps play cards in a boxcar in 1915. (From the Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Wandering and working in this autonomous way was, by and large, a privilege that belonged to able-bodied white men around the turn of the 20th century. The web site “In Search of the American Hobo,” researched by Sarah White for the University of Virginia’s American Studies program in 2001, reveals that the path of the hobo, who is basically just a migratory laborer, has never been an easy one. When they first emerged in the United States in the late 1800s, hoboes—like bums and tramps—were often vilified as useless vagrants by the communities they traveled to, where they might be beaten up, badgered by cops, or chased out of town. Which is a shame, because those townspeople obviously didn’t understand that hoboes have actually been essential to the rapid growth of America’s economy. According to Roger A. Bruns’ 1980 book Knights of the Road: A Hobo History, hoboes helped build the very railroads they traveled on, as well as the sewer systems, water lines, roads, bridges, and homes that have filled up the West.

“If you and I were to go out and look for hobo marks, we would never find them. Only a hobo knows where to look for a hobo symbol.”

Fortunately, hoboes have always had safe havens here and there in the United States, places populated by sympathetic folk. In particular, the small town of Britt, Iowa, has been a home base for the homeless laborer, starting in 1900. Britt, which hosts the weeklong National Hobo Convention every August and boasts a year-round Hobo Museum, has dedicated itself to celebrating hoboes and the culture they have created, while debunking the most pervasive myths about these vagabonds. The ’boes that come to Britt have a strict code of ethics they follow, and even a royal court.

To find the origins of the American hobo, you have to go back to the late 1860s, a time of upheaval in the United States. The Civil War (1861-1865) laid the country to waste, ripping apart families and destroying towns. After the war, soldiers on both sides often discovered they had no home to return to, and no job. Because they were used to the nomadic lifestyle of the military, they ended up wandering the country looking for work.

Workers, including hoboes, lay tracks for the Transcontinental Railroad. (Via “In Search of the American Hobo,” from the American Studies program at the University of Virginia)

“After the Civil War, the soldier went home, and there was nothing left,” says Linda Hughes, curator of the Hobo Museum in Britt. “So he grabbed whatever he could, got a hoe or a shovel, and took off on the road in search of work. These soldiers went from place to place, earning just enough money to go to the next spot. That’s how the hobo way of life started.”

Meanwhile, the invention of repeating long-arm rifles gave white settlers the upper hand over Native Americans and Mexicans in the West, which allowed the country to expand as it never had before. In his book, Bruns explains that many men found work rebuilding war-worn rails and laying tracks for the First Transcontinental Railroad, which was built between 1863 and 1869, paving the way for mining, logging, agricultural, and livestock enterprises—which often needed employees on a seasonal basis—to take hold in the far reaches of the continent.

“One of the biggest employers for the hoboes back then was the railroad system,” Hughes says. “They also did field work. They built courthouses, hospitals, and schools. A lot of them learned the masonry trade by constructing these buildings.”

An 1853 help-wanted sign for work on the railroad, which brought New York City laborers to Illinois. (Via “In Search of the American Hobo,” from the American Studies program at the University of Virignia)

At the same time, the Second Industrial Revolution was altering the American economy and job security, as big industries like steel, coal, iron, and oil production established footholds. Factory workers on newly mechanized assembly lines became subject to the whims of the global economy: When supply surpassed demand, low-skilled laborers were laid off. With each advance in machine technology, companies shrank their workforces, which Eric Monkkonen details in his 1984 book, Walking to Work: Tramps in America, 1790-1935. The railroad gave the freshly unemployed the opportunity to start over again in another place.

“Hoboes went from house to house and would ask women if they could have carrots, beans or potatoes out of the garden. In exchange, they did work for these women.”

The unemployment rate exploded in 1873, when Jay Cooke and Co., the bank that had financed the railroads, went belly up, creating the first major American depression. According to Bruns, work on the railroad came to a screeching halt, and more than 4 million people were canned, about a half million of them railroad laborers. In his 1967 book Hard Travellin’: The Hobo and His History, Kenneth Allsop explains that before the crash, the railroads had ignored the men hitching free rides on freight trains, figuring the manpower going to timber or mining companies would only help their cargo grow. During the depression, though, railroads cracked down on rail riders.

In her research, White found that prior to the Civil War, most towns had a merchant economy and a tradition of caring for their own homeless citizens, then called “tramps,” through acts of individual charity or by providing the down-and-out shelter in the local jail. But in 1873, more and more people started to roam, hopping trains to look for new work, and towns were flooded with complete strangers begging at people’s back doors, which were often located near the kitchen, the domain of the soft-hearted housewife.

A hobo jungle along riverfront in St. Louis in 1936. (Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress)

White details how newspapers and magazines wrestled with the “tramp problem.” Some people pushed for compassion, endorsing the idea that their cities and towns set up social safety nets for the itinerant workers. Writers on the other end of the spectrum felt downright venomous toward these vagabonds, suggesting women leave poisoned meat on their back porches. Towns and cities would pass strict vagrancy or trespassing laws. When wandering tramps arrived in Oakland, Maine, at the turn of the century, they would be imprisoned in a chair-shaped cage and mocked and tormented for a full day. As bleak as it was, hoboing gave many young men the hope that they could leave their hometowns, find work, and have great adventures along the way.

“Some of the hoboes that come to Britt now do not have legs, or they’ve lost fingers from trying to get on boxcars.”

If the roots of the hobo are fairly well understood, the origins of the term itself, which was first recorded in the late 19th century, are murky. It’s said that when soldiers were coming back from the Civil War, they would tell people they were “homeward bound,” which could have been shortened to “hobo.” The Latin phrase “homo bonus” means “good man,” so “hobo” could be derived from that. Migratory farm workers were known as “hoe boys,” which might mean they were the first hoboes.

Around the same time, hoboes were starting to organize and codify their world, known as Hobohemia. At a hobo campsite known as a “jungle” near the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line, a group of 63 hoboes—who called themselves “tourists”—discussed their frustrations about getting chased out of towns and train yards for having no money or obvious employment. They concluded they needed to form a union, as unemployed union members would not be harassed for coming to town. That night, they formalized the rights and duties of dues-paying union members, drawing up the papers for National Tourist Union #63, so named after the number of hoboes present.

During the Great Railroad Strike of 1922, railroads hired guards like this one to protect strikebreakers and prevent train hopping. (From the National Photo Company, Library of Congress)

The Tourist Union started holding annual Hobo Conventions in different cities around the country to gather yearly dues (one nickel per hobo), recruit new members, and reconnect with old friends. Every year, they would elect a new King, Queen, Crown Prince, Crown Princess, and Grand Head Pipe of the Hoboes. “When the Grand Head Pipe comes to town, hoboes have to go to him to find out what they can and cannot do,” Hughes says. “If there is trouble, he has to take care of it.”

The union sought to build a better relationship between itinerant workers and municipal and railroad police and hoped its conventions would improve their public image. Because these events drew so much attention, dozens of other similar groups formed and began hosting similar gatherings.

At the 1887 Tourist Union convention held on the banks of St. Louis, the union members drew up a Hobo Code of Ethics. The first law of being a hobo is “Decide your own life. Don’t let another person run or rule you.” According to the code, a hobo should try to keep himself clean and behave as a gentleman, respecting the local laws and officials, as well as railroad operators. A hobo shouldn’t get “stupid drunk,” because he’ll just make it harder for the next hobo who comes along. In the same way, he shouldn’t be too greedy with handouts or “cause problems in a train yard,” because another hobo might need the same resources in the future.

Hoboes at a jungle hang their washed laundry on a clothesline. (Via 1947project.blogspot.com)

He must always look for work, particularly jobs no one else will do. When he can’t find work, a hobo should make work for himself, practicing a craft like woodcarving, metalworking, or painting.

“A lot of hoboes are very talented,” Hughes says. “They’re always making something out of nothing. Others are gifted musicians. Liberty Justice, who passed away, was a great hobo singer. He entertained at the jungle all the time by the campfire. Many current and past hoboes have published their stories in books.”

The ethics code also tried to clamp down on hoboes known as “jockers” or “wolves,” who often took boys as apprentices and formed homosexual relationships with them as they showed them how to survive on the go. In turn, these lads were called variously “road kids,” “Angelinas,” “preshuns,” “posseshes,” “lambs,” or the slur, “fags.” As a euphemism for gay sex, hoboes would say, “he belongs to the Browning Sisters.” When the road kid was ditched by his mentor, he’d be known as an “auntie” or a “punk.” In the early 20th century, “punk” had become a slur against homosexual men, possibly the root of the term for knock-down carnival targets also called “punks.” These days, it’s applied to rebellious or wayward youth of any sexual orientation.

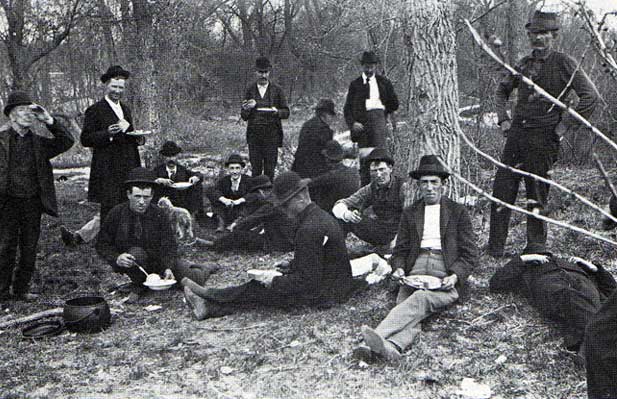

Men sharing a meal at a hobo jungle in 1895. (Via the Hobo Museum)

Taking a stand, the Hobo Code of Ethics Rule 13 states, “Do not allow other hobos to molest children. Expose all molesters to authorities; they are the worst garbage to infest any society.” It stands out because it’s the only act of violence specifically addressed in the 16-point code. The code also instructs hoboes to encourage runaway children to return home, help their fellow hoboes, and participate in the Union’s hobo court when someone is being reprimanded for violating the code.

“He did all of his traveling by rail and eventually would make his way home. He would have to live in the garage and re-court his wife all over again until he earned his way back in the house.”

According to the code, a hobo is expected to clean up after himself and pitch in with chores when he stays at a jungle. Hobo jungles, as recorded by American sociologist Nels Anderson in 1923’s The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man, have been located off the beaten path, but near a stream and reasonably close to a rail yard—and ideally near to a small town with a general store to procure bread, meat, and vegetables. Temporary camps would become permanent jungles if they were located near a spot with frequent train stops. The campsite usually had kitchen utensils and pots and pans, a clothesline for doing laundry, and a shaving mirror. Each day, a hobo would be expected to search for fuel for the fire and bring something for the communal soup known as “mulligan stew” or pay a quarter or half dollar into the food fund. Another can on the fire would be used for “boiling up” or delousing clothes. It was at the jungles that new hoboes would learn the ropes of hoboing from older, more experienced men, as well as stories and songs.

“A jungle is often in a wooded area, usually by the railroad tracks and by a river or a creek,” Hughes says. “It’s where the hobos would gather at night, and every one of them would have to bring something to put into the pot of stew at night. Then they would sleep next to the fire. The next day, a hobo would wash his one set of clothes in the river, to make sure it was clean for job-hunting, and hang it up in the trees. After their clothes dried, they’d put them on and go out and look for a job. They always made sure their jungle was clean, so it was ready for the next bunch of hoboes who came through.”

Two men help move a Hotel de Gink, or a hobo shelter run by hoboes, into an old button factory in New York City’s Bowery district on April 8, 1915. (From the Bain News Service, Library of Congress)

Those who didn’t pitch into the stew and ate others’ scraps were called “jungle buzzards” and thrown out. Those who left the camp in poor shape or stole from sleeping hoboes, a crime referred to as “high-jacking” committed by “yeggs,” were also driven away and ostracized by the larger community. At some jungles, fires at night were verboten, because the local police and railroad officials loved to scapegoat hoboes, and camping together at a jungle made them easy targets.

“If you have trouble on the road and a hobo sees you with that monkey’s fist, he will help you. Hoboes watch out after each other.”

“Back in the late 1800s, if you broke the Hobo Code of Ethics, you would be punished by other hoboes,” Hughes says. “You would be driven out of the towns where the hoboes worked, or you wouldn’t be able to camp in the jungle. You’d be considered a buzzard, because a buzzard isn’t a good bird.”

The Tourist Union voted to have the 1888 Hobo Convention in Chicago, where it stayed for 12 years, which isn’t surprising. Most American cities contained one neighborhood, called “the main stem,” that supported hoboes—New York City had the Bowery, San Francisco Third Street, L.A. South Main, and Baltimore Pratt Street. But Chicago’s main stem, West Madison, was by far the friendliest, and quickly became known as the Hobo Capital of the World. When farm work dried up in the winter, tens of thousands of hoboes—who chose to “eat snowballs,” or stay up north during the winter instead of “going with the birds” down south—would congregate in Chicago, each having saved up a “stake” of about $30 to pay for his months-long stay, which worked out to 10 to 25 cents a night, according to Carleton Parker’s 1920 book The Casual Laborer and Other Essays. The men could also pick up odd jobs at hotels or restaurants.

A barber gives a hobo a shave at New York’s Hotel de Gink in the 1910s. (From the Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

A main stem would typically have cheap hotels and boarding houses known as “flophouses” or “barrel houses,” cheap eateries, clothing stores, radical bookstores, charity missions, welfare and employment agencies, a barber college offering free haircuts and shaves, a drugstore, a cigar store, and plenty of saloons—which also offered check cashing, baths, affordable meals, and job information, Anderson learned. A man who’d earned a substantial stake at his job could blow off a little steam in the stem’s saloons, gambling halls, cheap theaters, and brothels, and he was always happy to share the wealth with his less fortunate hobo brethren. The Hobohemia bookstores and entertainment often drew nearby intellectuals, anarchists, and radicals to the district, while earnest believers working for the Salvation Army vied for the hoboes’ souls.

The flophouses were usually dirty, rat-infested places filled with tuberculosis-riddled residents. Some didn’t have beds, just sawdust on the floor, and others had cubicle-like structures instead of individual rooms. If they didn’t get sick from staying in flophouses, hoboes who hooked up with cheap prostitutes often suffered from venereal disease. According to Parker, four times as many hoboes stayed in a Chicago jail as they did flophouses during the 1890s.

Hoboes prepare mulligan stew at New York’s Hotel de Gink in the 1910s. (From the Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Back then, Chicago’s main stem served as an essential resource for finding the next job, gleaned from other hoboes and the employment agencies. The sleaziest of the private agencies were dubbed “slave markets” and their agents called “sharks,” who hired “man catchers” to wander the stem looking for workers. According to White, often, both laborers and employers were required to pay the agency. When a hobo accepted a gig thousands of miles away, he couldn’t be sure the job would be there when he arrived, or that he would have a means to get back.

“People lost everything they had during the Depression, so they had to live the hobo way of life to try and find work to survive.”

In 1899, three Chamber of Commerce leaders in Britt, Iowa—Thomas A. Way, T.A. Potter, and W.E. Bradford—were looking for a way to put their tiny town on the tourist map, and give it the credentials of a big city. According to H. Roger Grant’s 2012 book Railroads and the American People, Way and Potter read about the Tourist Union #63’s Hobo Convention in Chicago, and wrote a letter to the Grand Head Pipe, Charles F. Noe, to invite to him host the 1900 convention in Britt.

In Knights of the Road, Bruns describes the spectacle of this first convention, which took place on August 22, 1900: “fife-and-drum corps in silly hobo costumes playing ragtime music; banners; reporters from Chicago, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Omaha; horse races; barbequed ox; baseball; roulette; many gallons of beer. In the election ceremony at the fairgrounds, Admiral Dewey was elected to the presidency and Philippine Red as veep of Tourists’ Union No. 63. Editor W.A. Simkins of the Britt News wrote: ‘It was advertising that Britt was after and she got it.’”

A membership card for the International Itinerant Migratory Workers Union: Hoboes of America, endorsed by Jeff Davis, elected King of the Hoboes for life at a Pittsburgh hobo convention in 1935. (Via booksbrainsandbeer.wordpress.com)

According to Bruns, many real hoboes were insulted and disillusioned by this first Britt convention, as hundreds of fake ’boes had arrived in off-putting costumes: torn clothes, phony black eyes, and whiskers. Still, Britt garnered a reputation as “the hobo town.” The next Tourist Union convention didn’t take place until 1933, and was held, once again, in Britt, and since then has become an annual event.

“I was born and raised in Britt,” the Hobo Museum’s Linda Hughes says. “And the guys I grew up with lived through the Great Depression, hoboes like Steam Train Maury, Pennsylvania Kid, Slow Motion Shorty, the Hardrock Kid, and Connecticut Slim. Now we have a park that’s called the Hobo Jungle. But when I was growing up, these guys had to go out and make their own jungle along the railroad tracks for the convention. The town butcher would throw scraps of meat out for them at the end of the night so they could put something in their stew. And they went from house to house and would ask my mother and other women if they could have carrots, beans or potatoes out of the garden. In exchange, they did work for these women, be it sweeping the sidewalk or washing their windows.”

This monkey’s fist knot, which many hoboes wear around their necks, was made by Lady Marie and Hobo Spike for the Hobo Museum’s Linda Hughes. She says, “The metal ring mounted above the knot is made of several strands of wire and appears to be seamless. These rings are woven by Hobo King Frisco Jack and are presented, by him, at a brief ceremony where he declares the recipient an ‘Official Knight of the Road.’ It was a great honor for me to receive this at the 2001 East Coast Hobo Gathering in Pennsburg, Pennsylvania.” (Via the Hobo Museum)

Today, Hughes explains, those in hobo costumes aren’t trying to mock itinerant workers, and the authentic hoboes who regularly attend the convention know that. “They’re considered ‘hobos at heart,’ which is what I would be, a hobo at heart,” Hughes says. “I’ve never ridden the rails or lived that lifestyle, but I enjoy working at the Hobo Museum, the hobo culture, and these people.”

“As kids, our parents didn’t want us at the hobo jungle, but we would sneak down there. When those old guys came into town, it was like our grandpa came to see us.”

Some hoboes even wore a leather knot necklace known as a monkey’s fist in order to recognize one another. “Inside that knot is a ball bearing, which can be used for protection also,” Hughes says. “It’s a hobo symbol of sorority and fraternity. That goes back to the day of piracy—the sailors had to tie ships together using this type of a knot. At the Hobo Convention in Britt, Frisco Jack, a master knots-man and seaman, would always make knots for everyone. If you have trouble on the road and a hobo sees you with that monkey’s fist, he will help you or help you find someone who can help you. Hoboes watch out after each other. And they’ll watch out after anybody who says they’re from Britt.”

In 1905, according to Bruns, a hobo-by-choice named James Eads How established another hobo organization called the International Brotherhood Welfare Association in Cincinnati, Ohio, which set up so-called “hobo colleges” in cities like Cincinnati, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Baltimore, Buffalo, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. A hobo college would offer a place to sleep, wash up, and cook mulligan stew. Hoboes could also take free classes on industrial law, vagrancy laws, basic social science, how to prevent venereal disease, and how to get a job. The hobo colleges also attempted to usurp the disreputable employment agencies and become a reliable resource for job information.

A cover of “Hobo News” from the late 1910s. (Via the National Archives, WikiCommons)

How launched the first newspaper for and by hoboes, “Hobo Jungle Scout,” in 1913, which became “Hobo News” in 1915. At its peak, the paper had a circulation of 20,000 and included information on jobs and labor organizing, pieces on hobo lore and living the life, poems, and personal essays. Most of the writing was submitted by readers, and some of the most famous authors included Zandt Spies, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Eugene Debs. While the paper was mostly read by vagrants, some would sell the publication to make money, as the homeless do today hawking modern-day “street sheets.”

Jefferson “Jeff” Davis, a vaudeville performer and advocate for homeless workers, established another union in Cincinnati in 1908, called the International Itinerant Migratory Workers Union: Hoboes of America, which hosted its own annual conventions. He also came up with the idea of a self-sufficient boarding house run by hoboes, called “Hotel de Gink”—“gink” being another term for hoboes. His first boarding house, where hoboes would work for a few days to pay for their week’s room and board, opened in Seattle in 1913. Resident hoboes would provide each other services such as tailoring, barbering, and cooking. The idea spread across the country, and Davis opened several more himself, in Tacoma, Portland, and New York City.

Hoboes line up for a breakfast of coffee at the New York City Hotel de Gink. (From the Bain News Service, Library of Congress)

At the 1935 convention in Pittsburgh, Davis was elected King of the Hoboes for life. The “hoboes’ oath” on his union’s card declares, “I solemnly swear to do all in my power to aid and assist all those willing to aid and assist themselves. I pledge myself to assist all runaway boys and girls, and induce them to return to their homes and parents. I solemnly swear never to take advantage of my fellow men … and to do all in my power for the betterment of myself, my organization and America—so help me God.”

“With all the equipment that these farmers have nowadays, there’s no need to have hoboes on the farm.”

According to Todd DePastino’s 2003 book Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America, in 1908, 19 hoboes calling themselves the “Overalls Brigade,” led by hobo labor activist J.H. Walsh, traveled from Seattle through the Great Plains to Chicago and back, recruiting hoboes from boxcars, jungles, and main stems to organize and join unions. Hoboes were not so interested in the binding labor contracts that typical trade unions offered, but preferred direct action against exploitative employers, including strikes and sabotage. An honorable hobo would never break a strike or work as a scab.

Unlike other unions, such as Tourist Union and Hoboes of America, which promoted hoboes as hard workers, DePastino writes that Walsh pushed the idea that vagabonds were “sons of rest” who enjoyed the “simple life in the jungles,” free from the tyranny of bosses and the capitalist machine. Along the way, the Overalls Brigade sold a song sheet with four tunes including the 1890s ditty, “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum.” Thanks to Walsh’s efforts, the radical socialist union the International Workers of the World, or Wobblies, which had previously ignored itinerant laborers, turned its attention to organizing hoboes in the 1910s, at first on the main stems—where the IWW offered beds, kitchens, job information, and meeting halls—and then on farms.

A few of the marks hoboes would use. (Via the Hobo Museum)

At hobo colleges, on main stems, and in jungles, hoboes taught one another vital information for thriving. For example, hoboes would communicate with fellow travelers by marking fence posts at farms, railway bridges, and town welcome signs using secret codes made up of geometric shapes, stick figures, and slashing lines. Most of the symbols indicated how a hobo would be received at a home or in a town, whether they would meet a kind woman, a gentleman, a generous doctor, a cranky homeowner, a dishonest man, a gun owner, vicious dogs, or a police officer. These “marks” warned of danger, even indicating when you’d have to defend yourself, or promised safety. Others indicated where you could work for food or sleep in the barn.

“A lot of these guys never made it past the third or fourth grade in school and couldn’t read or write, so they made their own language,” Hughes says. “They did it in symbols. If you and I were to go out and look for them, we would never find them. Only a hobo knows where to look for a hobo symbol. Each symbol has a certain meaning so these hobos would know if it was safe or not safe to go into this community or to knock on this lady’s door.”

Hobo symbols mark the Algiers entrance to the Canal Street Ferry across the Mississippi River in New Orleans. The ferry is free for pedestrians or people on bicycles, so the symbols indicate it’s a “good way to go.” (Photo by Infrogmation, via WikiCommons)

For the less ethical wanderers, some of the marks instruct the hobo on how to manipulate the situation to get food and shelter like telling a pitiful or hard-luck story or faking an illness. While today, “an easy mark” means a person who’s easy to con, back then, the hobo “easy mark” symbol simply meant you could get food or a place to sleep with little trouble. Other marks told hoboes whether the place had help for the sick, or if the woman of the house would hand you some food. Certain glyphs communicated to yeggs whether a home was “worth robbing.” Some of the symbols simply gave hush-hush directions to a jungle or told hoboes when to stay quiet while passing through and hopefully go unnoticed.

Besides the glyphs, hoboes also developed their own jargon, documented by Nels Anderson in 1923 and Stephen P. Albert of the Original Hobo Nickel Society in 2004. Some of the phrases, which varied from coast to coast, have been adopted into common use: The “main drag” is the busy road in town, a “moniker” is a nickname, “moochers” are professional beggars, and the “graveyard shift” is late-night work. We still call stolen goods “hot,” coffee “Joe,” shoes “kicks,” food “chow,” drug addict “junkies” and use “hunky dory” for “all is well.” From ’30s gangster films, we know a state prison is “the big house,” your best clothes are “glad rags,” a young woman is a “broad,” a “flop” is a place to sleep, a “clam” or “smacker” is a dollar. A “cat” is now a young man, but back then it was a young hobo; “crummy” came from the hobo term meaning “infested with lice.” A “ding bat,” derived from “dingo,” was considered one of the worst kinds of vagrants, one who mooches off hoboes. A “hoosier” may still refer to a country yokel, while a “yahoo” is proud of his ignorance. Hoboes considered themselves far more worldly than these men.

An illustration from the 1873 book, “A La California,” by Colonel Albert S. Evans, shows a hobo making marks. (Via WikiCommons)

Despite this sense of hobo pride, many people associate them with clowns—and real hoboes hate that, Hughes explains. So-called tramp or hobo clowns first appeared in vaudeville and circuses in the late 19th century but had faded by 1917. However, during the Great Depression, hobo clowns made a comeback, as so many people could relate to being down on their luck. It’s worth noting that Otto Griebling’s and Emmett Kelly Sr.’s 1930s hobo clown characters rejected pity, always attempted to make themselves useful, even if they failed, and wanted to share what little they had. Red Skelton’s 1950s tramp clown, Freddie the Freeloader, however, was a straight moocher, further tarring the hobo’s reputation.

“At one point, we had some tchotchkes back in the museum that had clown faces, and the guys that come to this town didn’t like it,” Hughes says. “We removed those because, yeah, they are not clowns. One hobo, Adman, is adamant about that. When people ask him about that, he gets pretty ornery because he can’t stand that.”

Hoboes referred to themselves as “stiffs,” which is where we get the term, “working stiffs.” A hobo who carried his belongings tied in a piece of cloth known as a “bindle,” was called a “bindle stiff.” By contrast, men who never saw beyond the “walls” of their towns were “wallies,” “hooligans,” or the “home guard,” and hoboes were also called as “boxcar Willies” or “wandering Willies.” Tramps willing to work for a snack or a meal were known as “sons of Adam,” whereas a “barnacle” sticks to a job a year or more.

The caption on this 1938 Dorothea Lange photo reads, “More than 25 years a bindle stiff. Walks from the mines to the lumber camps to the farms. The type that formed the backbone of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in California before the war.” (Via Library of Congress)

Some hoboes even carried their bed rolls (called “balloons” or “fleabags”) on their backs. Often they tied tin tomato cans, used for boiling water, to their waists. “They always carried a clean set of clothes with them, because if you put on a clean set of clothes, you’ll always find work,” Hughes says. “They carried a few hygiene products such as a razor. Some of them always carried Rolaids and that type of thing, a bar of soap, and clean underwear. That’s about it. Steam Train Maury always carried everything in a tin can. They would make drinking cups out of tin cans. They would take wire and make a handle on it, and that way, they could always fasten that handle to their belt. So that way, that can was always with them.”

“After the Civil War, the soldier went home, and there was nothing left, so he grabbed whatever he could, got a hoe or a shovel, and took off on the road in search of work.”

It wasn’t uncommon for a hobo to also carry a short-handled shovel, known as a “banjo” and an “anchor” or pick, which gives you an idea the kind of work that was available for him. For example, “honey dipping” meant sewer shoveling or any other miserable digging job. “Glauming” was their word for harvesting crops—and also stealing. “House dogs” were willing to do housework for food, while a “wood butcher” would do carpentry and odd repair jobs. Some hoboes would “go junking” or scavenging scrap metal to sell for salvage. Other hoboes called “ky wah” sold trinkets on the streets.

A lot of the hobo slang offers a window into what the life was like: Terms like “hitting a New Yorker,” “O.P.C.,” and “snipes” refer to excitement of finding smokeable cigarette butts. Ironically, hoboes also called cigarettes “coffin nails.” Dogs that were particularly nasty were “bone polishers,” while newspapers that the hoboes would sleep under were called “California blankets.” Those who slept outside “covered with the moon” or wore a “windcheater,” or an old feed sack that would protect you from the weather. If you “pounded the ear,” you got to sleep in a bed.

Two hoboes walk along railroad tracks, after being put off a train, circa 1907-1912. (Via Library of Congress)

Guys who dug through garbage cans were “spearing biscuits,” and boarding-house owners who skimped on food were known as “belly robbers.” Hobo foodie slang is particularly amusing: Butter was “axle grease,” undercooked beans were “bullets,” ketchup was “red lead,” gravy was “sop,” and fried eggs on toast were “Adam and Eve on a raft.” A thin soup of potato water and salt was known as “Peoria.” Hoboes called bacon fat “pig’s vest with buttons,” whereas they could get a “stack of bones,” or boiled spare ribs, at a hash house for cheap. “Polishing the mug” meant washing one’s face and hands, which might be “cheesy,” or covered in dirt. “Scraping the pavement” meant to shave one’s face.

A hobo approaching a private home, called “slamming a gate,” would “toot the ringer,” or ring the bell at the back door, and a housewife might give him a “ball lump,” a sandwich or slice of cake wrapped in paper, as a “handout.” An even more generous woman might invite the hobo in for a “sit-down,” or a meal at the table. If a hobo was lucky, the dinner was served “collar and shoulder style,” meaning all the dishes were put on the table, and the hobo was allowed to help himself. Those who gave more than a hobo would expect were dubbed “angels.” Those who wanted to show off how generous they were would make a hobo eat an “exhibition meal” on their front doorstep.

Band members wearing hobo costumes pose on a horse-drawn wagon. (From the Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library)

At missions, a hobo could find food and a place to rest, but to do so, they had to embrace Christianity and evangelizing, and attend regular sermons. Food at missions was called “angel food,” and hoboes who at least claimed to be true believers were called “mission stiffs” or “Jesus guys.” Some tramps would “come to Jesus” or fake their salvation moment, just to keep receiving the mission’s charity. Hoboes were often philosophical types, too. If you stemmed in New York’s Bowery district, you might meet the “Bowery barometer,” a guy who espoused his ideas and shared information while sitting on the curb. A talker from the Wild West was known as a “sagebrush philosopher.” Those who “roosted” at the public library were called “library birds.”

“Hoboes always carried a clean set of clothes with them, because if you put on a clean set of clothes, you’ll always find work.”

The choice to reject permanent employment and travel alone in the early 20th century was safer and more viable for white men than any other demographic, so Hobohemia, like the rest of the United States, was abounding with racism. Hobo slang reveals the men were suspicious of not only people with a different color of skin, but Europeans with obvious accents: They called Russians “candle eaters,” Frenchmen “frog eaters,” Irishmen “flannel mouths,” West Indians or Negros from the tropics “monkey chasers,” Polish or Slavic workers, “bohunks,” Swedes “roundheads,” and Asians “ragheads.” In Citizen Hobo, Todd DePastino writes that itinerant workers of color or those perceived as “foreigners” were excluded from main-stem businesses and charities over white hoboes, and employers out in the fields often set up segregated camps.

Anecdotally, hoboes in the 1910s and 1920s seemed fine with mingling with Mexicans and African Americans in jungles and on the rails, but still felt the need to assert their superiority around the camps. Accordingly, many black men, who would be “outcasts among outcasts,” wouldn’t try riding the rails out of fear of racial violence, while many white hoboes refused to work for “checkerboard crews” that included African American employees.

Ernest Hemingway hopping a freight train between boxcars to get to Walloon Lake in 1916. (Via WikiCommons)

When it came to gender, hoboes often bragged they’d escaped the shackles of domesticity, i.e. the women’s sphere, DePastino writes. For most women in the late 19th century, marriage was the only option to avoid financial ruin. The patriarchal society insisted women needed protection and were too delicate to travel and work; those women who were homeless were practically invisible. Women who did live as hoboes often pretended to be men, as a woman wandering the streets alone would be assumed to be a prostitute. As more single women moved to the city to work as clerks and maids in the early 20th century, they would often take rooms at low-rent hotels on the main stem. It wasn’t until the ’20s that female hoboes known as “hay bags,” “high heels,” or “road sisters” became more common at jungles and stems. Before that, many hoboes got to know women as prostitutes, called “the burlap sisters” or “sales ladies,” who stayed in cheap brothels known as “zoos.”

Some hoboes, however, would live dual lives, settling down with one woman, but with one foot out the door, in case wanderlust struck. “The late Maurice ‘Steam Train Maury’ Graham was a five-time King of the Hobos, a mason from Toledo, Ohio,” Hughes says. “He fell in love with a young nurse named Wanda. They were married for 69 years, but he supported his family through a hobo way of life. His stories about living on the road and in jungles are incredible.

A driftwood painting of the famous late hobo Maurice “Steam Train Maury” Graham in the Hobo Museum. (Via the Hobo Museum’s Facebook page)

“Wanda always knew when he was starting to get the itch to leave,” she continues. “She’d come home from work and find a note on the table that would say, ‘Went fishing. Be back soon.’ It might be 5 to 7 years before Steam Train would come home. But in that time, he always sent her and their two daughters money. He also sent her a yellow rose, her favorite flower, on her birthday. He did all of his traveling by rail and eventually would make his way home. First, he would call her from the payphone booth down the street. Then, he would have to live in the garage and re-court her all over again until he earned his way back in the house.”

Hobo Rule No. 1: “Decide your own life. Don’t let another person rule you.”

Hobo slang also reveals all the shady characters you’d meet in this impoverished underworld and their tactics. Tramps known as “jiggers” would fake affection or employ “mush talk” (flattery) to get a handout. Others, called “slob sisters” or “tear babies,” would burst into tears to receive a woman’s sympathy. Some would even “flicker” or fake-faint. Some beggars called “ghosts” would fake illnesses, exaggerating their haggardness and pallor, and come up with a plausible “ghost story” to garner sympathy. A “phony stiff” sold fraudulent jewelry on the street. A “phony crip” (as opposed to a “straight crip”) faked a disability, while a “flopper” was a phony who is also panhandling on a busy sidewalk. Some tramps, known as “blisters,” went to the extreme of putting chemicals on their skins to give it the appearance of sores from disease.

Others resorted to stealing, from petty crimes like snatching fresh clothes from clotheslines, an act called “gooseberrying,” or swiping food and milk delivered at a doorstep, called “robbing the mail.” Then there were the more hardened criminals like robbers who could crack safes and were known as “knob-knockers” or “peatmen.” Informants, whom we’d call rats or squealers, were then called “beefers” or “stool pigeons.” But some tramps intentionally wanted to land in a “boodle jail,” one that felt like a good spot to stay for the winter. A stay in prison was called a “bit” or “jolt”—an especially short term was known as a “sleep,” whereas a lengthy one was a “long stretch.”

Boys hopping a freight train, circa 1925-1935. (Via Library of Congress)

Hughes says all the hoboes she’s known in her lifetime have been forthright and upstanding citizens, and not criminals. “The old guys have never been dishonest,” she says. “I trust them completely.”

In general, hoboes seemed more afraid of hospitals, which were rumored to have a “black bottle” of poison to give tramps, than jails. It’s worth noting that both hospitals and cemeteries were called “boneyards.” According to lore, the bodies of those who did “take the westbound,” or die, while at the hospital were used for medical students to practice on.

Naturally, the ’bo lingo has a whole set of terms dealing specifically with the rails. Every railroad had a special tongue-in-cheek nickname, like All Tramps Sent Free (Atchinson, Topeka and Santa Fe RR), The Bum’s Own (Baltimore & Ohio RR), Canned Meat & Stale Punk (Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul RR), Foul Water & Dirty Cars (Fort Worth & Denver City RR), Less Sleep and More Speed (Lake Shore and Michigan Southern RR), Ma and Pa RR (Maryland & Pennsylvania RR), and the Never Come, Never Go (Nevada County Narrow Gauge RR).

A man lying prone atop a railroad passenger car in a 1907 photo titled, “Tramp life—how Jack London traveled on a passenger coach.” (From the Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Freighthopping, or “beating a train” was both a thrill and a high-risk way to get around, costing many a hobo life and limbs. Some hoboes worked out deals with the train’s brakeman or another crewman, paying him a “salve” of 10 cents per hundred miles or 20 cents for an overnight ride. But, according Sarah White’s research, railroad police officers or “bulls” could be barbaric, beating tramps and hoboes within inches of their lives, throwing them off trains in the middle of nowhere with nothing, or shooting them point blank. Hoboes called being pushed off a fast train “hitting the grit,” and those who kill themselves jumping in front of the train were “greasing the tracks.” Some bulls known as “hobo nighthawks” even disguised themselves as tramps. At jungles and stems, hoboes passed word to one another about which lines were “bad roads” and which were “open roads,” or easy for hobo travel.

“When hoboes come to town, they will ask for work. We’ve found them work painting houses and washing windows.”

Ideally, a wanderer would find an “empty” or unused boxcar to climb into. Some would “catch him on the run” or “flip a rattler,” as in, jump on a moving train. Clueless young hoboes, who were looking for adventure more than work, would stare out the boxcar door drawing too much attention to themselves—the wiser hoboes referred to them as “scenery bums.” Riding a loaded car could lead to getting crushed by the cargo inside, and railroad officials were concerned about the less honorable tramps who made off with merchandise. Hoboes that got into “reefers” or refrigerated cars sometimes froze to death. If a hobo sat with his legs outside the “side-door pullman,” they could be cut clean off when the train went over a hill, causing the door to slide shut. After that, he’d be known to other hoboes as a “halfy.”

According Bruns’ Knights of the Road, if you couldn’t find an open boxcar you might have to “ride the blinds,” the front platform of the baggage car—the baggage piled up inside the car provided a nice cover, but the engine’s fireman could hit a trespasser with water, coal, or hot ash. Others would ride atop or “deck” a train, risking that a sharp curve could throw them off. Some hoboes would find a secure spot between the “bumpers” or on one of the car’s ladders. The riskiest way to travel was to “ride the rods,” or hold onto a specific rod under a passenger coach. According to Edwin A. Brown’s 1913 book “Broke”: The Man Without a Dime, between 1901 and 1903, 25,000 train hoppers were killed on the rails, and about 25,000 were injured, disfigured, or disabled. The slang terms for those who lost limbs on the rails include “sticks” (lost one leg), “peg” (lost a foot), “fingy” (lost fingers), “blinky (lost an eye), “wingy” (lost both arms), “mitts” (lost one or both hands), “righty”(lost the right arm and leg), and “lefty” (lost the left arm and leg).

“If you were to fall off a boxcar, your chances of survival would be pretty slim,” Hughes says. “Some of the hoboes that come to Britt now do not have legs, or they’ve lost fingers from trying to get on boxcars. It’s very serious to ride a rail; it can be deadly.”

While hoboes were always known for their craftsmanship, in 1913, the new Buffalo or Indian Head nickel gave them a new canvas on which to express themselves. The thick, wide profile of a Native American chief on the coin let hoboes carve new faces onto the coin, and these artworks would sell for 25 cents, or five times their worth. Hobo nickels became a special currency that hoboes would use to barter among themselves.

A family who traveled by freight train to Toppenish, Washington, in August 1939. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, from the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

But by the 1920s, the market for hobo labor was slowing down. According to sociologist Nels Anderson’s 1940 book Men on the Move, low-skill hobo work for farms, ice harvesters, and lumber companies was being done by machines. Most of the infrastructure of the United States including rails, sewers, bridges, and homes were built, and the West had been settled to the point that farms had plenty of local labor. According to Errol Lincoln Uys in 2003’s Riding the Rails, after the Great Depression hit in 1930, about 4 million adult and 250,000 teen migratory laborers hit the hobo circuit, but the romance was zapped out of it. These workers were often desperate and hungry rather than eager for adventure.

The Dust Bowl (1931-1935) in the Great Plains drove even more farm workers onto the open road. More than ever, White writes, young single women who lost their jobs went wandering. For their safety, they would dress as men or take a male hobo as a lover. In the 1930s, entire families—men, women, and children—would go on the road looking for work in a car, and hoboes were named “rubber tramps.”

Jeff Davis, left, and his “rubber tramp” car with graffiti, including “Davis,” “Keep Off,” “Hobo King,” “Hands Off,” and “Traveling DeLux,” in 1924. (From the Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress)

“People lost everything they had during the Depression,” Hughes says. “So they had to live the hobo way of life to try and find work to survive. That’s when women and the children went with the men on the rails in search of work. One of our oldest hoboes still living is Hobo Lump, a former Hobo Queen. She lived that life and rode the rails for many years. She’s almost 90 years old.”

Thanks to the thriving post-World War II economy and the new social safety net of FDR’s New Deal, hobo culture all but died out during the 1940s. However, train hoppers and rubber tramps (with RV campers) maintain hobo traditions even to this day. Now, freight trains—compared to the first steam engines—run so incredibly fast, that trying to catch a moving one is often lethal, so smart hoboes only jump aboard when the train is stationary.

A photo of a 20th-century hobo in a denim jacket covered in patches. (Via the Hobo Museum)

“Today, you never get on a train that’s moving; you only get on a train that is completely stopped,” Hughes says. “You always ride the rails with a buddy, never by yourself. You get a boxcar that’s got the openings on the sides or one that has an opening on the top, what’s known as a gondola car. You never ride in a boxcar that’s refrigerated or a grain car. You can ride underneath a grain car on the rods, but you’re only about 6 inches from the rails, which is very dangerous. You’ve got to have certain things with you. You never travel without water, something across your face, warm clothes, or boots. But any of this is dangerous. At the Hobo Museum, we do not promote rail riding.

“Since 9/11, it’s gotten really tough to ride the rails,” she continues. “We don’t see as much of that, but the lifestyle still exists because there are many, many people that travel from job to job, be it by motor home, bus, bicycle, whatever. A lot of young kids are doing it. When they come to town, we ask them why, and they won’t tell us. If they’re running from something or if they’ve had bad parents, we don’t know. Times have changed. We don’t see that Depression Era hobo who goes from door to door because nowadays you’d probably get shot doing that.”

Hughes admits that there isn’t as much work for hoboes in 2015. “It used to be that hoboes would come to town and help the farmers,” she says. “But those days are gone. With all the equipment that these farmers have nowadays, there’s no need to have hoboes on the farm.”

The collection at the Hobo Museum includes hobo clothing, walking sticks, knots, and cups made out of cans. (Via the Hobo Museum)

Still every year in August, as many as 125 real hoboes make their way to Britt for the Tourist Union #63 Hobo Convention. In 1974, three hoboes, Steam Train Maury, Hood River Blackie, and Feather River John, started the nonprofit Hobo Foundation in Britt, and today, the foundation has both hoboes and full-time Britt residents on the board. In the 1980s, the foundation purchased the town’s vacant Chief Theater for $1 and turned it into a museum featuring objects that had belonged to hoboes who passed away. Today, the museum has the artifacts of 30 late hoboes.

The bulk of the Hobo Museum’s collection are items like hand-carved walking sticks, handmade musical instruments, tin cups, and monkey’s fists carried by Depression Era hoboes, as well as their clothes, stories, and art. There, you can see artifacts belonging to late Hobo Kings such as Mt. Dew and Steam Train Maury and vintage photographs of hoboes. Robes and crowns worn by former Kings and Queens are also in the collection. “Texas Madman’s homemade blue-jean coat is back there,” Hughes says. “He did a lot of stitching. He made a quilt with the rail lines on it and one with the hobo symbols on it.”

At Mary Jo’s Hobo House restaurant, hoboes sign this piece of driftwood. (Via the Hobo House Facebook page)

Linda Hughes runs the Hobo Museum while her sister, Mary Jo Hughes, owns Mary Jo’s Hobo House restaurant, which is also filled with hobo memorabilia, across the street from the museum. On the same block, Britt features Queen’s Gardens, planted in honor of Hobo Queens. The town cemetery even contains a special Hobo Memorial section, where the Hobo Foundation provides free burial plots to Hobo Kings and Queens.

A Britt park called Hobo Jungle, which is near the Soo Line rail, has a special shelter house with showers and restrooms for hoboes to sleep in when they’re in town. Hoboes raised money for the structure, and with the help of Britt residents, built it in 1992. Hoboes start to congregate in Hobo Jungle Park a week before the convention.

“When they come to Britt, they will ask for work,” Hughes says. “We have found them work painting houses in town and washing windows. We’ve had them clean the museum and paint the shelter house down at the Jungle. If they want to stay in the jungle and eat there, they either have to bring canned goods or put a few bucks in the can so they can eat.”

Songbird and Cindy Lou are the reigning Hobo King and Queen, wearing the honorable Folger’s Coffee can crowns. (Via the Hobo Museum)

Tourist Union #63 is still collecting dues at the Hobo Convention, now $5 a year per member. “If one of the hoboes needs a little help, that money goes to support them,” Hughes says. “One year, one of the guys had a dental issue when he came to town, so they took him to the dentist here in town, and they paid him with that money.”

Aside from the 100 or so living hoboes, the Hobo Convention draws 20,000 gawkers to Britt, a town that has only about 2,200 full-time residents. Hughes says some groups even chose the Hobo Convention as an event to center their family or class reunion around. The City of Britt has its own Hobo Committee, which puts on the festivities for the Hobo Convention in downtown Britt. Many of the attractions seem unrelated to hoboes and more like just typical summer fair fare: There are professional musicians hired by Britt, carnival rides, a flea market, a circus show, and a classic car and truck show. But, Hughes says, there’s plenty of true hobo culture, too.

The kitchen at Hobo Jungle Park in Britt, Iowa, got an update in 2014. (Via the Hobo Museum)

“Down at the Jungle, hoboes will play music,” she says. “On Thursday night, the hoboes also bless the wind and the fire, and then they start their entertainment. On Friday, the hoboes have the hobo memorial service in the morning, and then they go to the area nursing home. A lot of the children and grandchildren of the Depression Era hoboes come to the memorial service to pay their respects. They’ve gotten to be friends with other hoboes’ families, so it’s like a family reunion for them. On Saturday, we have the hobo parade, the mulligan-stew feed, and after that, is the King and Queen coronation.”

Hughes is thankful that she got to grow up around hoboes. “As kids, our parents didn’t want us at the jungle, but we would sneak down there,” she recalls. “The hoboes were very kind-hearted people. When those old guys came into town, it was like our grandpa came to see us. We respected them, and they respected us. They taught us to always have a set of clean clothes so we’d always find work. They’d say, ‘When you pack your suitcase, roll your clothes. Don’t fold your clothes because you’ll end up with wrinkles.’ They were always teaching us something.”

The exterior of the Hobo Museum in the old Chief Theater in Britt, Iowa. (Via the Hobo Museum)

(The Hobo Museum is located at 51 Main Street South in Britt, Iowa; for more information on visiting call (641) 843-9104. The National Hobo Convention takes place in Britt the second week in August. For further reading, check out Sarah White’s web page “In Search of the American Hobo” for the American Studies program at the University of Virginia as well as the following books: Roger A Bruns’ “Knights of the Road: A Hobo History”; Todd DePastino’s “Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America”; Nels Anderson’s “The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man and “Men on the Move”; Kenneth Allsop’s “ Hard Travellin’: The Hobo and His History”; Eric Monkkonen’s “Walking to Work: Tramps in America, 1790-1935”; Errol Lincoln Ulys’ “Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression”; Carleton Parker’s “The Casual Laborer and Other Essays”; and Cliff “Oats” Williams’ “One More Train to Ride: The Underground World of Modern American Hoboes.” To learn more about hobo nickels, visit the Original Hobo Nickel Society’s web page. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Looking at Tramp Art with Author Clifford Wallach

Looking at Tramp Art with Author Clifford Wallach

How a Gang of Harmonica Geeks Saved the Soul of the Blues Harp

How a Gang of Harmonica Geeks Saved the Soul of the Blues Harp Looking at Tramp Art with Author Clifford Wallach

Looking at Tramp Art with Author Clifford Wallach Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians

Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians Hobo NickelsHobo nickels are actual U.S. coins (usually Buffalo nickels but sometimes J…

Hobo NickelsHobo nickels are actual U.S. coins (usually Buffalo nickels but sometimes J… Tramp ArtPopularized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the term "tramp art" refers …

Tramp ArtPopularized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the term "tramp art" refers … RailroadianaThe railroads built America: up through WW2 they were the dominant form of …

RailroadianaThe railroads built America: up through WW2 they were the dominant form of … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

My brother has been a Hobo all his life, he goes by name of Van, Vance or Harold VanHorn and we haven’t seen nor heard from him in over 25 years. If you’re out there call and let us know you are ok. 248-877-3292 Brother Kenny

My Dad rode the rails in the early thirty’s when he was in his teens.

When the second world war broke out he was able to find steady employment.

Every now an then when he had a few beers under his belt he’d tell me of

his travels. He always reminded me that he was a hobo and not a bum.

Do you know the n ame of people that traveled to toppenish, wash

My Uncle Larmon Peter Wright was a hobo in early 1900s looking for any information or written letters with mention of his name.

I was compelled to read your whole article. I couldn’t quit. As the youngest of 5 only 2 are left.I’m 68 today! my dad didn’t give much info,but often threatened to leave us and jump the train again. He had told us of traveling with his buddy “Skinny”they were on a train and a fire broke out..and they were able to put it out. After that they were not bothered when they hopped on. He was born 1910 and left home when he was a young teenager. so he was probably hobo about1925 ish. Has anyone heard or seen an article about the train fire. Last name Jacobs

I wanted to share this on my facebook page. Alas !

Very interesting article!

We have a postcard that my grandfather, Troy Stanley, sent to his mother while on the road. The front of the postcard has a photograph of him and three other men at a camp. We are curious to know how these photographs were turned into postcards. His comments to his mother include the line “you haven’t heard from me because I got busted!” The postmark is from the early 1900’s. Thank you for this wonderful article.

Like in every era, there are bad people, one hobo roughed my grandmother up, because this once she had no extra food, the family dog attacked him and he ran off.

My Great Uncle George Hopkins (Slim, or Hopie) was a hobo in the 20’s and the 30’s. He wrote his memoirs down in 1980’s. The family typed them out and made a 323 page book out of them. I am retying the book and trying to put it in order. Trying to verify facts and so forth. Has anyone heard of him. He has some really great stories and I hope to have a book published before too long, about his life.

An excellent article and required reading if you are speaking of the ‘homeless.”

My name is Tommy Nelson I wrote a song from stories told me by my Dad when he had to go on the Hobo to feed his family. He always said, like others, he was not a Hobo but went on the Hobo. I recorded this song in the 50s, “Hobo Bop” on the Dixie label, which became one of the first Rock A Billy songs. It is in the Rock A Billy Hall of Fame. The Hobo life has always fascinated me with their stories of the road. Thought about them a lot while I was on tour myself all over the country. Thanks for your story

Beautiful article, brought back memories of my wandering days in the 70’s. I was a hitch hiker, traveling with my “insurance company”, a dog named Jedediah Smith. I spent a season amongst the fruit tramps in the Okanogan WA apple orchards. I walked through the jungles to get to my Bartending job in Brewster. The hobos were great people, i learned a lot from them. Any shady characters left me alone since my dog was always at my side. I ate and sang with them in the orchards and the jungles. Thank you

Really a great read. My Dad born in 1909 worked all his life on the railroad and now I know where he got his slang words from. I found a hobo camp when I was a kid.

Thanks for the stories.

Met Pennsylvania Kid in Tacoma WA about 1972 He stayed at the hippie home with us we squatted in, in town for a short while. He had a big round top cowboy hat and coat full of buttons and. I had seen him on the Johnny Carson show as well. He was a good promotor. I will never forget him remarking when wanting to bathe that he only used lye soap to wash with as it killed everything. He also carried a prominent knife for protection. He was an alright fellow.

I am in possession of Jeff Davis original traveling trunk, an oil painting by Jeff Davis, and several copies of the newsletter – all willed to me by my grandfather… To whom (the Museum in Britt?) should I donate these items?

100 or so living hoboes? – agree to disagree.

I have more than 100 current hoboes on my Facebook page right now…

There are many more than 100, but the migratory work is different. Now it’s busking and cannabis harvest, tourism jobs like cutting coconuts/palm leaf art in Key West. Beets every year, too. And some of the new hobo lingo is a little silly, and perhaps inappropriate.

– Abby

This gold mine of information about the hobo should be a part of our educational system. It is hard to imagine this part of American history, it should be cherished and remembered. My two brothers and I visited the hobo’s camped along the Sioux River at Watertown South Dakota in 1950. They were a good bunch of people trying to make their way, on their own in a world that had let them down. I enjoyed reading your historical work.

My Granpa Otis was a man with a wide variety of abilities. He farmed, blacksmuthed, raised sorghum cane and made sorghum with his mill, was a lumber man, hewed cross ties, cut Cypress trees for lumber, raised mules, raised Angora Goats and sheared them fir mohair. For some reason lost in time he would hop a train and go elsewhere for work. Once he tried to hop a train and broke his leg. While laid up from having a broke leg he learned to play the fiddle(violin) and afterward would play and call square dances at Dunhams Eddie on Black River just north of the Arkansas line over in Missouri.

Such a fascinating article. I remember my Grandfather telling us (in the 70’s) that their family was so poor growing up that his older brothers left home because they were just more mouths to feed and their home life was hard too. Of the stories (that I don’t remember), I understood that my Uncle Andy really took to the life. They were always “hoboes,” never bums or tramps.

Wonderful article! Allowed, someone like me, from somewhere Európe, the place called Hungary, to get to know about this part of American history. Fascinating, that is áll i can say! Thanks

My grandfather was orphaned at age 14 in the 1920s. No social nets back then so he took to the rails hopping trains from job to job until he landed in the coal camps of Appalachia. There he married, started having more and more mouths to feed, and finally was forced to follow the Hillbilly Highway to Baltimore for marginally safer and better paying jobs. Thank goodness! Kindest, most decent and hardest working man one could imagine. He died at age 67 of blacklung.

I photographed Brii in early 2000. Have large number of 5/7 prints. Will give to a non profit Email me bob k

Please contact me regarding the pictures used in your Hoboes article.