After 150 years, America is still haunted by the ghosts of its Civil War, whose story has been romanticized for so long it’s hard to keep the facts straight. In our collective memory of the war, men are the giants, the heroes remembered as fighting nobly for their beliefs. Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865, has achieved the status of legend, the moment a broken country started to reunite, even though that’s not exactly true.

“A Lincoln official was completely flummoxed when he said, ‘What are we going to do with these fashionable women spies?’”

What’s been largely lost to history is how remarkably influential women were to the course of the Civil War—from its beginning to its end. Without Rose O’Neal Greenhow’s masterfully run spy ring, the Union might have ended the months-old war with a swift victory over the Confederates in July 1861. Instead, the widow leaked Union plans to Confederate generals, allowing them to prepare and deliver a devastating Union loss at the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as the First Battle of Manassas, which caused the war to drag out for four more years. Elizabeth Van Lew, another woman running a brilliant spy ring who also happened to be a feminist and a “spinster,” was instrumental to the fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on April 1, 1865, leading to Lee’s surrender eight days later.

“Elizabeth Van Lew was probably the most valuable spy of the Civil War—male or female, North or South,” says author and historian Karen Abbott. “She basically won the war for Ulysses S. Grant, and it’s astounding that she’s not a household name.”

Top: Confederate spy Belle Boyd, 17, in her riding gear, with gun in her belt, circa 1861. Above: Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew, 43. (Photos from “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

All the ways women directly engaged in the War Between the States—from posing as male soldiers, to seducing secrets out of politicians and generals, to operating as spies, couriers, and diplomats—are explored in Abbott’s engrossing narrative nonfiction book Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War, which comes out in paperback September 8. Through these four women’s eyes, we see the whole behind-the-scenes story of the war unfold.

Abbott grew up in Philadelphia in the ’80s, where the Civil War had long faded from the public consciousness. When she moved to Atlanta as an adult, suddenly she was confronted with regular reminders of the Confederate States of America, an illegal government—formed by seven slave states and later joined by four others—that tried to secede from the United States between 1861 and 1865 because newly elected President Abraham Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery into new Western territories. The Confederacy started a war with the states that stayed loyal to the United States government, known as the Union, on April 12, 1861, when its soldiers fired on the U.S. military-controlled Fort Sumter outside of Charleston, South Carolina.

“It was a culture shock,” Abbott remembers. “I saw Confederate flags on lawns and heard jokes about ‘The War of Northern Aggression.’ One day, I was stuck in traffic one day behind a pickup truck with a bumper sticker that said, ‘Don’t blame me. I voted for [Confederate President] Jefferson Davis,’ which drove the point home that the Civil War seeps into the daily-life conversation down South in a way it never does up North. It got me thinking about the Civil War, and my mind always goes to ‘What were the women doing?’ And not just any women, what were the ‘bad’ or defiant women doing?”

Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow, 48, and her 9-year-old child, Little Rose, in the courtyard of Old Capitol Prison in D.C., where she was being held on suspicion of treason in 1862. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

So Abbott went on a hunt for female spies, and four names came up right away. For each woman, she found an abundance of primary source materials, such as personal archives and hand-written books. Elizabeth Van Lew and Rose O’Neal Greenhow were operating central spy rings for the Union and the Confederacy, respectively—and they both documented their experiences thoroughly. Abbott uncovered two other women who had engaged in Civil War subterfuge and recorded their personal histories in great detail: Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmondson, a Canadian expat who had served as a Union soldier as her male alter-ego, Franklin Thompson; and Maria Isabella “Belle” Boyd, a brazen teenager who operated as a Confederate courier and made a game out of stealing weapons from Union camps.

“Elizabeth Van Lew was probably the most valuable spy of the Civil War—male or female, North or South. She basically won the war for Ulysses S. Grant.”

“The more I read about these four women, the more I realized that their stories intersected in interesting ways,” Abbott says. “One woman’s behavior was always affecting another woman’s circumstances, and they were always running into the same people. Rose was watching Emma march on Capitol Hill, and her spying was affecting Emma. Belle had a great scene where she was telling off Union General Benjamin ‘Beast’ Butler, putting him in his place in this very Belle-like brash way. Then, in the next scene, Butler is recruiting Elizabeth to be a spy for the Union. So it was like a big puzzle, and I had a lot of fun figuring out where they all fit.”

Reading the book, however, you get a sense that these four recorded stories—all the perspectives of white women—are simply the tip of the iceberg in terms of women’s involvement in the war. In Washington, D.C., Greenhow recruited plenty of society women and girls as her scouts, including 16-year-old Bettie Duvall and even her own 8-year-old daughter, Little Rose. For years, Van Lew relied on a local seamstress and her paid African American employees, including Mary Jane Bowser, a well-educated 21-year-old who posed as an illiterate enslaved woman inside the Confederate White House in Richmond and gathered critical intelligence. Unfortunately, Abbott wasn’t able to unearth any of Bowser’s own accounts of her role in the spy ring.

The house where Belle Boyd and her family lived during the Union occupation of Martinsburg, Virginia. (2015 photo by Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress)

“Mary Jane is really the other spy in my story,” Abbott says, “I scrounged and scrounged for every scrap of information I could find on her. Reportedly, Mary Jane kept a diary of her time as a spy in the Confederate White House. But one of her descendants in the 1940s or 1950s accidentally threw it out, not realizing what they had. When you hear that, of course, it’s just like a stake in the heart of every historian—to know that an invaluable diary is lost for good. But I put in everything I could about her and also about all the other African Americans that were instrumental to Elizabeth’s operation.If I had had more primary source material, I’m sure my book would’ve been subtitled Five Women Undercover in the Civil War, but as it was, I had to fit her under the umbrella of Elizabeth’s purview.”

Abbott says she would have loved to have featured African American women more prominently in the book, but by and large, she was not able to find enough source material revealing their perspectives. The one exception was Harriet Tubman, who also used her slave escape route known as the Underground Railroad, where African American hymns spread messages through coded lyrics, to operate a spy ring herself. But Tubman’s story was much too large to be contained within the scope of the Civil War.

The abolitionist Harriet Tubman, pictured circa 1860-1875, escaped slavery and helped others do the same. She also worked as a Union spy. (Via Library of Congress)

Even though it was the home base for Union soldiers, Washington, D.C., in many ways was a Southern city, and the U.S. government was riddled with Confederate sympathizers. For example, the brothers of President Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, were high-ranking Confederate officials. Much of the war was fought along the Potomac River, which forms the border between Maryland and Virginia, the two states that touch the District of Columbia. And those border states in particular were not monolithic in their support of the Union or the Confederacy—the political timbre often depended on which county you were in. Before the Confederate capital moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia, in May 1861, Richmond was home to a significant number of Unionists.

“Many of the Washington residents had come from Maryland, which, although it was a border state, had a lot of slave owners,” Abbott says. “The slave markets had been rampant in D.C. The nation’s capital was a porous, ambiguous place to be, and you didn’t know where anyone’s loyalties lay. All of these people who now worked for the Confederate government had once worked for the United States government and therefore knew a lot of the protocol, the policy, and the insiders who maybe could be turned. The fact that Lincoln’s White House was pretty much open to visitors was just astounding to me, too. Everybody was eavesdropping.”

In this climate, women made great spies precisely because of the way 19th-century society underestimated them. During the Civil War, they “were able to take society’s ideas about the weakness of womanhood and brilliantly exploit them,” Abbott says. “Women were always supposed to be the victims of war, not the perpetrators. One of my favorite quotes in the book is from a Lincoln official, who was completely flummoxed when he said, ‘What are we going to do with these fashionable women spies?’ The idea that women are not only capable of treasonous activity, but they are also capable of executing it more deftly than men was something that had never occurred to these men. The women were either above suspicion, in the case of somebody like Elizabeth Van Lew, or below suspicion, in the case of somebody like Mary Jane Bowser. Nobody even knew she could read, and of course, she was probably the smartest one of them all.”

Union Private Frank Thompson, who was born Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmondson in New Brunswick, Canada. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

If they were caught, or on the verge of being caught, female spies could play dumb, helpless, or indignant, declaring “How dare you accuse me? I am a defenseless lady!” Abbott says men didn’t know how to handle it. “Another one of my favorite scenes in the book is the hearing where Rose O’Neal Greenhow is being charged with treason against the United States,” she says. “The prosecution is questioning and badgering her, and she’s turning the tables on them and putting them on the defensive brilliantly. Then one of her interrogators says ‘I don’t think you are bent so much on treason as mischief.’ And it’s like, ‘Mischief? I basically won the battle of Manassas for the South, and I’m up to mischief?’ Even when the evidence was clearly laid out right in front of the men, she was just guilty of ‘mischief,’ because what more could a woman be guilty of?”

The elaborate fashion of Victorian society ladies gave these women plenty of places to hide messages and other contraband—from their big updo hairstyles to their huge hoop skirts to their corsets laced tight against their skin. And according to the decorum of the day, a proper gentleman would never try to peek under a woman’s skirt or ask her to strip. Even taking down one’s long hair was seen as a sexual act and requesting a woman do so was considered highly improper.

Confederate spy Belle Boyd, circa 1855-1865. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

“I like the way these spies used gender as this physical and psychological disguise,” Abbott says. Belle Boyd, for example, was “no Elizabeth Van Lew,” but she made good use her layers of petticoats and crinoline. “If she was really effective at anything, it was at smuggling. She recruited other Southern women to smuggle weaponry, like muskets and sabers, under their hoop skirts. The 28th Pennsylvania Regiment near Harper’s Ferry woke one day to find about 200 sabers, 400 pistols, 1,400 muskets, and cavalry equipment for 200 men were gone.”

These women also employed a lot of ingenuity to convey messages in an era before Americans even had telephones or radios. When Greenhow, a 47-year-old widow who was living in Washington, D.C., received word of the Union Army’s plans to march on Manassas, Virginia, in 1861, she encrypted the message using a simple cipher similar to the one in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Gold Bug.” Then she put the message in a tiny black silk purse, and wrapped it in Bettie Duvall’s long, dark hair. To deliver it to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, Duvall dressed as a simple farm girl, claiming she needed to cross the battle lines to return home from the market. Twice daily at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., Greenhow also transmitted messages to scouts for Confederate Captain Thomas Jordan waiting across the street from her home at 16th and K streets by opening and closing her window blinds in Morse code. If she were in public, she could telegraph a Morse-code message using her hand fan. After she was captured, she still coded messages in embroidery and letters that would read like pure drivel to an outsider.

Rose Greenhow’s silk purse and part of her encrpyted message to Confederate General Beauregard. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

Before the Civil War, Elizabeth Van Lew, her mother Eliza, and her brother John—the family of a late wealthy hardware-business proprietor in Richmond, Virginia—allowed their family’s 15 slaves to work to buy their freedom and then offered to hire them all back as paid employees. Elizabeth even spent some of her inheritance, about $200,000 in today’s money, to buy slaves at auction, just to set them free. While Van Lews were unusual in their treatment of enslaved people, they initially weren’t alone in wanting Virginia to remain a part of the Union: Before the war, two-thirds of the Virginia Convention of 1861 voted against secession. But from the battle of Fort Sumter on, the city became progressively more pro-Confederacy, making it a dangerous place to openly express Unionist sentiments.

“Women were always supposed to be the victims of war, not the perpetrators.”

Keeping her allegiance to the Union undercover, never-married 43-year-old Elizabeth used her social standing to gain permission to minister to Union prisoners of war being held at an old tobacco warehouse in Richmond. With the help of her African American employees, she provided important prisoners an escape, even using a secret room in her mansion to hide them. When she visited the prison, she often carried contraband in a French plate warmer, but when she overheard the guards say they planned to search it next time, she returned to the prison with the warmer filled with scalding water. She also relied on the prisoners for updates from the front lines and what they overheard from prison guards. She taught them how to use straight pins to puncture a sequence of holes near specific letters in the books she lent them, which would spell out secret messages.

“Elizabeth would bring books and clothing to the prisoners, anything she could get away with bringing them,” Abbott says. “She would take a pin and punch out letters in sequence in these books. The letters would form words, and the words would form sentences. At first, she was asking questions like, ‘What Union soldiers are imprisoned there?’ But then she got more sophisticated with it and started asking about infantry positions and what gossip they were hearing among the Confederate guards. She would ask ‘Do you hear anything about what General Lee is up to?’”

The Libby Prison was the second Richmond tobacco warehouse converted into a Confederate military prison. The guards whitewashed the walls to make it easier to spot escapees. (Via Library of Congress)

But she didn’t limit her resources to prisoners of war. When Confederate First Lady Varina Davis announced she was looking for a new servant, Van Lew paid her a visit and offered the services of Mary Jane Bowser. What Davis didn’t know was that Bowser was more like a daughter to Van Lew, who sent her to Quaker school in Princeton, New Jersey, and then to Liberia as a missionary for four years. While Bowser played the role of a wide-eyed, uneducated enslaved woman, she was able to read and memorize Jefferson Davis’ top secret plans left on his desk, which he wrote in plain English before encrypting them. She would hide her notes and maps for Van Lew by sewing them into the waistband of some of Varina’s dresses and then delivering them to a Union-sympathizing seamstress, who would take them apart and save the messages for Van Lew. If she had an urgent message, Bowser would hang a red shirt from the White House clothesline. “I thought that was remarkable, the way that they were able to smuggle messages in and out through Varina Davis’ own dresses,” Abbott says.

To communicate this intelligence to Union officials in D.C., Elizabeth had a chain of Union sympathizing couriers, horsemen, and boat operators from Richmond to Washington who would hide escapees and deliver letters, pin-pricked books, and Richmond newspapers to the U.S. War Department. Through her family’s hardware business, she and her brother John filled out an invoice with coded information on the Confederate forces in Richmond: 370 iron hinges (3,700 calvary), 30 anvils (30 batteries of artillery), and 40 vises (4,000 shock troops). John delivered such a message to the North himself, claiming he had to visit Philadelphia to collect on a prewar debt. Union General Benjamin Butler would also write Elizabeth letters in invisible ink, and then cover it with a mundane letter written in regular ink from a pseudonym to an aunt.

First Lady Varina Davis. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

Belle Boyd, a 17-year-old shopkeeper’s daughter from Martinsburg, Virginia, who offered her spying services to the Confederates regardless of whether they wanted them, was far less discreet than Greenhow or Van Lew. She employed a wide range of costumes and identities—from a Confederate private to a demure Southern maiden to a flamboyant warrior for the South—and often brought her little black lapdog on courier missions. She even made a costume of a white-hair dog skin that fit over her pet so she could carry messages on his back.

“Belle could become whoever she needed to be in the moment,” Abbott says. “It’s one of her great gifts. She was also incredibly charismatic. I love that she made her dog sort of complicit in all of her spying. She also had a pet crow that she taught how to talk, and the bird said ‘Stonewall’ referring to General Thomas J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, whom Belle was obsessed with. I mean, come on! I think one reporter said she wanted to ‘occupy his tent and share his dangers.’ If I were Stonewall Jackson, I think that would’ve frightened me more than anything that the Union Army had in store. Belle was just somebody you could not make up.”

General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

Emma Edmondson—a 19-year-old Canadian who had been living as a Bible salesman using the name Frank Thompson in Flint, Michigan, two years before the war started—decided to travel to Washington, D.C., to enlist as soldier when she heard about the war, motivated by her Christian belief that slavery was wrong. While Frank was definitely a side of Edmondson’s identity, she had to “disguise” her female body by avoiding taking off her uniform. Lucky for her, staying dressed was shockingly easy to do, as the men serving in the U.S. Army rarely bathed or changed clothes, and they often wandered into the woods to do the “necessaries.” The stress of training could have stopped Edmondson’s period, but bloodied rags could also pass as bandages for wounds. After she volunteered to serve as a spy between lines, she added other layers of disguise: She once painted her face with silver nitrate and donned a black wool wig to pose as a enslaved man, and later, played the part of an Irish farm girl—a woman convincingly passing as a man had to pretend to be a woman again.

“The 28th Pennsylvania Regiment woke one day to find about 200 sabers, 400 pistols, and 1,400 muskets were gone.”

“I couldn’t believe that anyone could get away with disguising themselves as a slave,” Abbott says. “I’m assuming nobody expected a white person to disguise himself as a slave. I’m sure the other slaves were a bit more skeptical of Emma’s charade than the white people. It’s just bizarre the things that people were able to get away with back then. Today, women wearing skirts would not deter anyone from searching them, if the need arose. These things could have happened only in that particular time period.”

Edmondson was actually one of 400 known women who passed as men to serve in the military during the Civil War. While the War Department required that Union recruits undergo a full physical exam, which would including stripping naked, most doctors were so overwhelmed by the flood of potential soldiers they cut corners and approved the volunteers with a quick glance. Very few of the women posing as soldiers were living as men before the war. Some female privates were fleeing abusive parents or husbands. Some women didn’t want to be separated from their husbands who were enlisting. Others, like Edmondson, felt deeply committed to their sides’ cause. Most of them, Abbott speculates, were impoverished and in desperate need of the military stipend, $13 a month for Union privates and $11 for Confederates. Abbott was most puzzled by how few got caught.

After the war, Emma Edmondson changed her name to Edmonds and began living as a woman again. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

“I came to the conclusion that they were getting away with it because nobody had any idea what a woman would look like wearing pants,” she says. “People were so used to seeing women’s bodies pushed and pulled in these exaggerated shapes with corsets and crinoline. The idea of a woman in pants, let alone an entire Army uniform, was so unfathomable that they couldn’t see it, even if she were standing in front of them. Emma had such a great advantage over the other women: Here’s somebody who already honed her voice and her mannerisms. She was already comfortable as Frank Thompson, who was a real person to her. She wasn’t going to make any of the rookie mistakes, like the woman who, when somebody threw an apple to her, reached for the hem of her nonexistent apron, trying to catch the apple. My favorite story is the corporal from New Jersey who gave birth while she was on picket duty, like, ‘The jig is up!’”

While Abbott considers Edmondson “gender fluid,” she decided to write about her with a “she” pronoun, as a woman, as opposed to writing about her as a transgender man with a “he” pronoun, in part because Edmondson abandoned her Frank Thompson persona after she deserted the Army—out of fear she was about to be exposed and arrested—on April 17, 1863, and never brought him back. She changed her name to Emma Edmonds and started living as a woman again.

“After the war, Emma ended up getting married and having children,” Abbott says. “Frank Thompson was just as legitimate a person, I think, to Emma, but somebody that she also decided ultimately that she was not. He was, I think, somebody who was convenient to her in that time. She was clearly attracted to men during the war because she fell in love with a fellow private, but who knows if she was bisexual. That’s certainly a possibility that she might not have felt comfortable exploring or even knew how to acknowledge in that time period. She was definitely gender fluid, and Belle was probably as well.”

Frank Leslie’s 1863 cartoon “The Art of Inspiring Courage” shows a woman threatening to join the Union army if her husband doesn’t. (Courtesy of Karen Abbott)

Part of Emma’s impulse to create Frank Thompson came from a desire to escape the dreary life as a farmer’s wife she saw laid out before her in New Brunswick, Canada, before the war: She suffered at the hands of her abusive father; she saw how miserable her sisters were as farmer’s wives; and at 16, she was set to be married off to a lecherous elderly neighbor. Men seemed to be the source of her misery; but they also had all the power to be free. In her writings, she described men as “the implacable enemy” and wrote how she hated “male tyranny.”

According to Emma’s memoir, she was inspired by a novel she bought from a peddler, Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of Revolution, which told the story of a woman who disguised as a man and became a pirate to liberate her kidnapped lover. After Fanny freed him, she continued to pose as a male pirate for several weeks, as the pair had more adventures on the high seas. Supposedly, this story fueled Emma to cut her long hair, run away from home, and start living as Frank in the United States.

The title page of “Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of Revolution,” the book that inspired Emma to start living as a man. (Via Harvard University, Houghton Library)

“She was very much like a second-wave feminist, way before the second wave,” Abbott says. “She recognized that men had the power, and the way for her to attain any of that was to become a man. But she definitely felt comfortable as a man, and I think that that was a vital, integral part of her personality.”

What’s surprising throughout the book is the way old men, like Emma’s neighbor, would openly ogle teenage girls. Back then, the age of sexual consent was right after puberty, which could be as early as age 10 or 12. By age 17, a rival of Belle Boyd’s already dubbed her “the fastest girl in Virginia or anywhere else for that matter.”

“The amount of commentary I read on Belle’s appearance was really shocking to me,” Abbott says. “Everybody had something to say about her body, her face, how ugly she was, how beautiful she was, how she was ‘fast’ how she was. In 19th-century parlance, of course, they didn’t use the word ‘slutty,’ but said she was a ‘fast’ woman. There was so much commentary on her physical presentation and her sexuality, which was interesting, considering that she was only a 17-year-old girl.”

Belle Boyd, circa 1860-1865. (Via Library of Congress)

Boyd often used this fascination with her sex appeal to her advantage—flirting with or disappearing in closets with Union soldiers and generals to get the lowdown on the military. “In diaries in the South, nobody admitted to anything more than flirting,” Abbott says. “Nobody was talking about actual intercourse. But you had a Northern reporter saying that Belle was ‘closeted’ for four hours with General James Shields. What was she doing with him for four hours? It’s one of the charming qualities of 19th-century writing. You just have to fill in the blanks and wonder exactly how far things went.”

“Rose felt completely free using this child, whom she adored and doted upon, in her spy exploits.”

Boyd and Edmondson weren’t alone in breaking the sexual and gender taboos of the era. In D.C., people whispered about Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow, who was still considered very beautiful at 47, and all her late-night male visitors. Even before her spying career, influential men of all political stripes—from abolitionists, secessionists, Union military officials, diplomats, and Republican and Democratic Senators and Representatives—shared her bed and spilled their secrets. Even though Greenhow was jailed for leading her spy ring and then exiled to Richmond, she was not received as a hero in the Confederate capital. The Southern ladies snubbed her, gossiping and clucking about her sexual liaisons.

“If I admire anything about Rose, it’s that she was brilliant, clearly, but she also just didn’t give a damn,” Abbott says. “I think she was operating from a place of depression, to the point she didn’t care what others said. She was going to seduce somebody if it was going to be to her advantage in some way, and neighbors be damned. She was completely slut-shamed, but she didn’t care, which is refreshing. The only time she really was given her due by other women was in death. Then, they decided that she had been slut-shamed enough.”

Rose O’Neal Greenhow, circa 1855-1865. (Via Library of Congress)

For all the tittering and ideas about propriety and good manners, during the Civil War, women lived in fear that soldiers from the other side would rape them. This fear was particularly heightened in the South when Union soldier began to march on Confederate border towns in Virginia in 1861.

“It was a PR war where they were trying to persuade people how atrocious and barbaric the other side was.”

“I read a lot of diaries of Southern women, and they were all terrified of being raped by the Yankees,” Abbott says. “They would talk about how to conduct themselves around Union men, what to be wary of, how to keep them out of the house or how to give them what they asked for, if they wanted food or bounty from the farm. Being raped by a Union private was one of the worst things that could’ve happened to them. I mean, today, rape is still one of the worst things that could happen to any woman. But the concern at that time, unlike today, was about protecting the woman’s virtue and avoiding being sullied. The men in their lives didn’t want their women’s reputations and their families to be damaged by an assault from a Yankee.”

In fact, when we first meet Belle at her home in Martinsburg in July 1861, she shoots and kills a Union soldier for lunging at her mother. “I’m sure she was terrified that they very well could have sexually assaulted her mother,” Abbott says. “The Union generals in charge of her case decided that there was enough evidence of self-defense to acquit her, or to at least not hold her accountable. I’m sure there were some other factors at play, namely that it was early in the war and Lincoln was still practicing appeasement. He didn’t want to create any Southern martyrs. He just wanted things to go away quietly. But also I’m sure there was a legitimate threat there, and Belle acted accordingly.”

Two men Emma found handsome: Her friend and confidante, 20-year-old Union private Jerome Robbins, and 34-year-old Union General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

Speaking of morality, all four women in the book see themselves driven by good Christian ethics and God’s will. For Edmondson and Van Lew, slavery was an abhorrent sin that needed to be stopped, while to Greenhow and Boyd, slavery was a part of what they saw as God’s natural order.

“Belle, to me, seems like one of those kids who just takes on their parents’ politics,” Abbott says. “She had been raised in the South, she had family in the Confederate army, so she’s being a Confederate because her parents told her to be. She hasn’t grown up yet and figured out her own politics. It was more of a challenge to write about Rose. Obviously, she was racist, her views were abhorrent, and she said some despicable things. I had a hard time with her at first. I tried to come at her in a way where I could have some empathy for her and write her so she wasn’t just a stock bad character. I wanted to try to find some humanity in her so people could at least understand where she was coming from.

“Rose’s whole life had fallen apart in the years leading up to the war,” Abbott continues. “She had lost five children in four years. She had lost her husband in a freak accident. Her father had been killed by a family slave. And the war cost her access to her friends and the White House. Her Democrat friends—including President James Buchanan, whom she was very close to—were no longer in power. I think she was desperate and also incredibly depressed. That’s not to excuse anything she said or did, but in understanding her, those are the conclusions I came to.”

Rose Greenhow’s cipher. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

The fact Greenhow employed her own child to exchange messages for Necco wafers with Confederate scouts while Greenhow was under house arrest reveals just how desperate she was. “She felt completely free using this child, whom she adored and doted upon, in her spy exploits,” Abbott says. “In her mind, her daughter was safer taking these risks than she would be if the North won and they were under Yankee control. She was operating from a place of extremism.”

“It was the first time an American woman was sent on a diplomatic mission like that.”

It’s not to say that many Yankees fighting against the spread of slavery in the war were not racists themselves. Even abolitionists could be racist on some level. “Elizabeth wrote things that today sound incredibly racist. For example, she wrote, ‘The Negros have black faces, but white hearts,’ which, to her, was elevating black people to a level of humanity equal to whites which was, at the time, a progressive sentiment. But oh my God, that’s a really racist thing to say. But she did risk her life for the cause and would not have hesitated to die. I do believe she considered Mary Jane and all of her African American comrades in her spy operation to be equals to her, and she had great love and respect for them.”

While Boyd did not go as far as Van Lew by offering her slaves freedom or pay, Boyd was quite attached to her personal slave, Mauma Eliza, whom raised Boyd since she was a small girl. Boyd even taught Eliza how to read, which was illegal. When the war ended Eliza stayed loyal to Boyd.

“They were complicated relationships,” Abbott says. “I’m guessing some of freed slaves worried about finding work or having no place to go, and that’s why a lot of them decided to stay with the comfort of the devil they knew. Here was a family that treated Eliza well. Belle clearly had great affection for her and taught her to read. Eliza even spoke of Belle fondly, and decades after the war, Belle sent gifts for Eliza’s grandkids. A friendship and a caring developed there beyond that mistress relationship. It was obviously very different than what Elizabeth did with her family slaves, but Belle had her own way. I’m sure Eliza was more of a mother to Belle than her own mother.”

Union soldiers stand at attention in front of the U.S. Capitol on May 13, 1861. (Via Library of Congress)

Edmondson, serving as Frank, is the one character in the book who’s actually in the trenches. She was one of 50,000 volunteers that arrived in the nation’s capital for military training after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861. She was a sharpshooter, whereas many of the boys and men coming from cities didn’t even know how to handle a gun. But actually fighting battles was only a small part of the Union’s strategy. The “Anaconda Plan” was actually the tactic that won the war for the North in the long-term. The United States government poured money into setting up a blockade along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean and stationed ground troops all around the border of the Confederacy, destroying bridges, railroad tracks, and telegraph wires to starve the South of food, supplies, and communication from the outside world.

Which means very little of the resources went toward the Union troops themselves. Even when they were camping in Washington, D.C., the men had only stale bread and water contaminated with bacteria for sustenance. Even in the summer, they wore heavy woolen socks with boots that didn’t distinguish left from right.

“At first, the Lincoln administration thought the war was going to be over in 90 days,” Abbott says. “I’m guessing that they just didn’t feel like the men’s shoes were of paramount importance. If the war was going to be over in 90 days, so why bother spending inordinate amount of money on proper and expensive boots? When you consider the sheer amount of money they had to start spending on weaponry and enforcing the blockade, it was just prioritizing.”

Famous Union detective Allan Pinkerton and his men tailed and captured Rose O’Neal Greenhow. Here he is with President Abraham Lincoln (center) and Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand (right) at the Battle of Antietam, Maryland, September-October 1862. (Photo by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress)

Because Edmondson felt it was against her Christian belief system to shoot another person, she volunteered for medical duty. As the Union recruits who joined the war effort in the spring and summer of 1861 languished in Washington, D.C., many of them killed time by visiting local brothels or inviting “camp followers”—or prostitutes that moved into their camp—to share their tents. So in her first months of service, Edmondson treated an endless parade of male genitalia ravaged by venereal disease. “Emma definitely had her work cut out for her being a nurse,” Abbott says. “Luckily, she wrote really colorfully about that.”

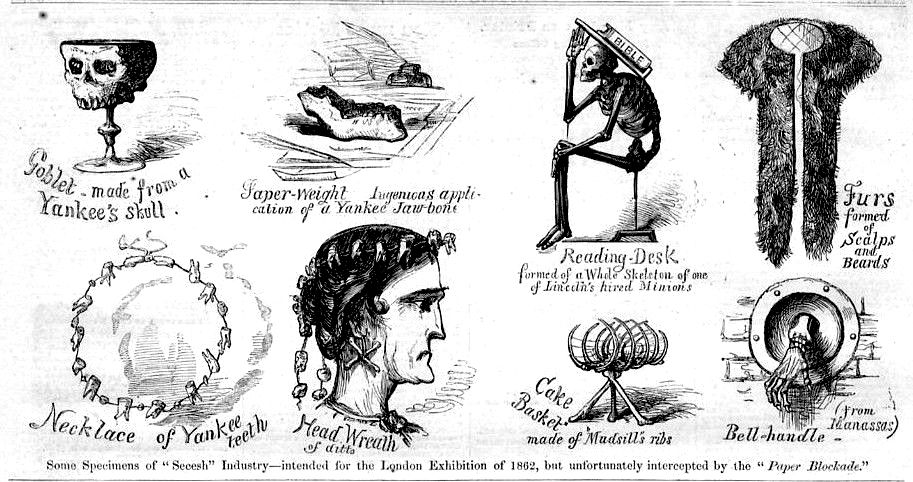

The First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861—which took place in Manassas, Virginia, 25 miles west of D.C.—was a grisly affair, killing 4,500 men on both sides, with minié balls and cannonball shells ripping flesh and tendons and rending limbs. Edmondson held dying soldiers choking on their own blood and assisted the surgeon in amputations. Northern accounts of the battle make Confederates sound like absolute maniacs who were slashing throats and cutting off the heads of dead Union soldiers to punt them. Some claim Confederates even cut off ears, noses, and testicles to save as souvenirs. Abbott says that many of these stories were likely exaggerated to make the Confederates seem more monstrous and rally Northerners around the cause. That said, some Southerners did claim to save and wear Yankee bones as charms. Men and women passionately devoted to the Confederacy often talked about “Yankee fiends” or “Yankee beasts” with the amount of dehumanizing scorn usually reserved for black people.

Published in “Harper’s Weekly” in 1862, this engraving was entitled “Some Specimens of the Secesh Industry” and depicted a “Yankee skull” goblet, a necklace of Yankee teeth, and other Yankee-bone items. Click image to see larger view. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

“Both sides obviously exaggerated what the other side was doing,” Abbott says. “It was a PR war where they were trying to persuade people how atrocious and barbaric the other side was—which is not to say that some atrocities weren’t committed. There were definitely women claiming to wear jewelry made of Yankee bones and things like that. But nobody knows exactly what happened on that battlefield. It’s not like anybody saw every single thing that happened. It’s hard to know what’s true and what’s not.”

After the Union’s crushing defeat at Bull Run, General George McClellan was promoted to command the Army of the Potomac and decided his men were simply not ready to fight. The Union maintained its picket against the Confederates on the other side of the Potomac River for a full eight months before engaging in battle again. In fact, most of the Union deaths during the whole Civil War war—two times as many as from battle wounds—were from diseases such as typhoid fever, malaria, and dysentery, the latter of which was caused by the polluted water the men drank. At the time, medical knowledge was so poor that men were treated with mercury and other toxic substances. As the winter of 1861 came and went, men serving in Confederate army camps died by freezing to death.

Confederate operatives used acorn-shaped containers, shoved in their rectums, to smuggle medicines like quinine and other good across Civil War battle lines. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

During the months-long delay, soldiers along the pickets often struggled to contain their hostility, shouting insults and sometimes even trading fire. Other times, though, both sides got fed up with it all, put down their weapons, shared coffee and cigarettes, and traded stories about their girlfriends.

“The women had to carve out their own lives, different from the ones that they had led in their spoiled antebellum years.”

“These people were literally in each other’s faces,” Abbott says. “As much as the dehumanizing language was common, there were also those unexpected moments of grace when they would set their arms down and play cards or talk about their lives and show pictures. I like those little glimpses of humanity among enemies, because it was overall a terrible, ugly war.”

According to a story on TruthOut, many Southerners recruited to fight were too poor to own slaves and resented the Confederacy for getting them into this mess. By October 1862, General Lee saw his ranks depleted by 60,000, with a third of those men gone AWOL. Some more ardent Southern deserters even fought actively to undermine the Confederacy. The impoverished white men who did fight for the South often did so only because the Northerners were on their turf.

“I definitely think that some Confederate soldiers didn’t care at all about the cause,” Abbott says. “There’s a famous quote where somebody asked a Confederate soldier why he was fighting, and his answer was, ‘Because they’re here.’ This guy didn’t care about slavery one way or another, but the Union troops were on his land so they had a fight. There were turncoats on both sides, and in the Shenandoah Valley, the Union and Confederate lines were so porous. You could go from one town to the next, and the sentiment would be completely changed.”

The Van Lew mansion in Richmond, circa 1905. (Via Library of Congress)

In a similar way, Elizabeth Van Lew was also loyal to her state—she believed in Virginia and wanted it to stay a part of the Union and abolish slavery. “You hear about all those Southern generals who once fought for the United States government who resigned because they were Virginians first,” Abbott says. “She considered herself a Virginian first, too. She believed that Virginia belonged with the rest of the country, and it was her duty that she stay and fight for Virginia. She could have just fled up North, removed herself from all the danger, and had a cushy existence, but she chose not to.”

In 1863, Rose O’Neal Greenhow was recruited by Jefferson Davis to board a “blockade runner” with her daughter, Little Rose, and escaped to Europe, where she would serve a diplomatic role and attempt to persuade officials in England and France to acknowledge the Confederacy as a legitimate government.

“People were just astounded by her,” Abbott says. “She was very intelligent, fluent in French, and clearly politically savvy. Here was a woman who could discuss politics with as much acumen and insight as any man, and it was to the men’s credit that they acknowledged her prowess on these matters. The fact that Jefferson Davis thought highly enough of her political skills to send her as a lobbyist to Europe was quite remarkable. It was the first time an American woman was sent on a diplomatic mission like that.”

U.S.S. Fort Donelson was known as the Robert E. Lee during the Confederacy. The steamer was a blockade runner when this picture was taken in 1864. (Via Library of Congress)

As charismatic as she was, Greenhow’s efforts were fruitless, as both countries could foresee the fate of the rogue band of slave states. The Anaconda Plan was working: By 1864, Confederate soldiers had no shoes, and the prices of food and goods in the South were exorbitant, $1,000 for a barrel of flour and $1,200 for a suit. Southerners were resorting to eating rats, dogs, and cats, and thanks to Van Lew’s spying, Grant stopped a Confederate exchange of $380,000 worth of tobacco for bacon in Fredericksburg, Virginia. In Richmond, citizens rioted over food. In August 1864, Grant issued Circular No. 31, which offered Confederates pardons and a financial incentive to desert their army.

“The blockade strategy really clinched everything for the North long term,” Abbott says. “People were literally starving. It goes a long way to explaining animosity that Southerners have toward the North today. I imagine that people who had ancestors who didn’t even own slaves heard stories of their grandmother or great-grandmother having starved to death. Cities like Atlanta were literally burned to the ground and destroyed.

“It was brilliant of Grant to institute this open-door policy for any Confederates who might want to come up to the North,” she continues. “They wouldn’t be charged with treason, and they would be fed. They would actually have some boots. It was probably starting to sound pretty good to a bunch of Confederate soldiers by that time.”

An 1861 cartoon map illustrates Union General Winfield Scott’s plan to crush the Confederacy economically. It is sometimes called the “Anaconda Plan.” (Via Library of Congress)

Greenhow met her end when her ship from Europe was caught returning to Virginia by the blockade on October 1, 1864. Instead of surrendering to Yankees, she attempted to flee with a heavy purse holding gold coins around her neck and drowned.

“The idea of a woman in pants was so unfathomable that they couldn’t see it, even if she were standing in front of them.”

Edmondson, who had deserted her regiment and returned to living as a woman on April 17, 1863, was, like many of her fellow soldiers, haunted by the war the rest of her life, physically as well as mentally. She had contracted malaria during her tour of duty and, thanks to being thrown from horses and mules, suffered injuries to her left hip and foot that contributed to her perpetual poor health. In 1864, she came out with her memoir of living as man during the war, The Female Spy of the Union Army, and a year later, it was republished with the title Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, selling 175,000 copies, a tremendous number for the time. Eventually, she demanded that she receive a pension from the U.S. Army like any other soldier. Because other soldiers were willing to vouch for her, the U.S. government began to pay her a stipend of $12 a month in 1886. She finally succumbed to malaria 12 years later, at the age of 56.

“By the end of the war, she was completely mentally and physically wrecked,” Abbott says. “On top of that, she had been dealing with stress that the men never had to deal with, wondering if her sex was going to be discovered and facing the repercussions of that, then knowing that Frank had been listed as a deserter, which she could have been hanged for. But she was able to keep it together to carve a successful postwar life, which I find remarkable. I can’t imagine how infuriating the fact she was not getting a pension would’ve been and I’m glad that she fought for that. What an accomplishment! It took a lot of nerve, when here she was admitting that she had duped everybody. She was an interesting mix of strength and vulnerability all the way through her life.”

The entrance to the secret room in Elizabeth Van Lew’s mansion. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

In the South, the end of war didn’t do much to change the mindset of former Confederates against the racism that perpetuated slavery. Only three days after General Lee surrendered, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate spy John Wilkes Booth. Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Confederate-sympathizing Tennessean, took the office and declared the war over on May 9, 1865; a day later, Jefferson Davis was captured. As president, Johnson aggressively fought any Republican effort to create civil rights or economic opportunities for 4 million newly freed black people in the South and pardoned many of the Confederate officials. No treason trials were held; not even for Davis, who served a two-year jail sentence. A group of vigilantes called the Ku Klux Klan lynched and tormented formerly enslaved people all over the South, many of whom had no choice but to work as indebted sharecroppers for the plantations that once enslaved them.

“Rose would seduce somebody if it was going to be to her advantage in some way, and neighbors be damned.”

The so-called “Radical Republicans” in Congress took over Reconstruction of the South in 1866, passing the 14th Amendment in 1867, which extended civil rights to formerly enslaved people, and the 15th Amendment in 1870, which extended voting rights to black men. They deployed the U.S. Army to govern the South under martial law in 1867, which lasted until 1870. After General Grant was inaugurated as president in 1869, he worked to suppress the KKK and enable black men to vote and run for office in the South, as businessmen from the North headed South to rebuild railroads and cities and pursue other economic interests there. In 1872, Grant signed the Amnesty Act pardoning 150,000 former Confederate troops. Grant’s successor Rutherford B. Hayes ended the “Radical Reconstruction” in 1877, focusing on reuniting the divided country, but he still couldn’t convince Southerners to accept civil rights for blacks. In the 1870s and 1880s, Southern authors, including Jefferson Davis, started to rewrite the story of the Civil War, a popular narrative that became known as the Lost Cause, wherein Confederates fought nobly to preserve their genteel antebellum way of life.

“The Civil War was this bloody, horrible thing, and then it became a romantic ideal,” Abbott says. “It was almost the last straw for Elizabeth when Virginians erected a statue of General Lee on the main street in Richmond in 1890 and hundreds of thousands of people were thronging it in adulation. It was like, ‘Really? I risked my life and we won the war for this? This is what Virginia is going to be now?’ It was a moment of clarity and a horrible disappointment. She realized what she had lost and what she had won, and the two weren’t quite equal.”

With all this romanticization, Belle Boyd, who may have suffered from a mental illness like bipolar disorder, was able to turn herself into a celebrity of the Lost Cause. In the late 1860s, she started billing herself as “Belle Boyd, of Virginia” as she improvised tales from her 1865 memoir, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison, onstage in places like Washington, D.C., and New Orleans; sometimes she’s even ride onstage on a horse. But in 1870, she had checked into an insane asylum for a brief stay because her mind “gave away,” and then she avoided the spotlight for 15 years, traveling from place to place and struggling with her mental health. Women claiming to be Belle Boyd popped up all over the country, in Martinsburg, in Philadelphia, in Atlanta, and in Corsicana, Texas. She returned to the stage in 1886, opening a one-woman touring show, “The Perils of a Spy” that also played in Northern states such as Iowa and Ohio. The story hinged on her most famous moment—the day she rode through the front lines at the Battle of Front Row to breathlessly inform Stonewall Jackson of the enemy’s strategy.

“She recognized that men had the power, and the way for her to attain any of that was to become a man.”

“Her big claim to fame is how she literally ran into the oncoming fire to warn Stonewall Jackson about the Union forces that were converging,” Abbott says. “Stonewall might have already had that information, but she confirmed it for him. She rewrote her narrative however she saw fit in the moment, which I thought was one of her more charming characteristics. She had an endless imagination. No matter what she was doing, she could find a way to sort of spin it for herself. I love that when she married her first husband, the Yankee, during the war, the first thing she worried about was ‘What is Jefferson Davis going to think? Let me write and assure him that I’m going to convert my husband to the Confederate side.’ Of course, Jefferson Davis was at home not only worrying about losing the war, but his own son had just died. Belle Boyd’s marital situation was the last thing on his mind, but of course, to her, Jefferson Davis was just as obsessed with it as she was.”

On the other hand, Elizabeth Van Lew, who had no way to leave Richmond after spending her fortune on her spy ring, was reviled as a traitor in her hometown. She was called erratic, eccentric, mentally unstable, and masculine, and some people even whispered she was a witch. She continued to pioneer for feminist and anti-racist causes: She campaigned for women’s suffrage and, thanks to President Ulysses S. Grant, became the first female Postmaster General of Richmond, hiring both female and African American employees. She even insisted on being called “postmaster” instead of “postmistress.” Mary Jane Bowser, who had fled to the North in early 1864, returned to Richmond after the war and became a teacher for 200 black children. Meanwhile, John Van Lew lost the hardware business, and Elizabeth petitioned the United States government to help her recoup some of her financial loss, but only received $5,000 in compensation for her spying that brought an end to the war. After she died at age 82 in 1900, locals claimed to see her ghost, which they spoke of to frighten their children saying, “Crazy Bet will get you!”

Elizabeth Van Lew’s Union-sympathizing brother, John Van Lew. (From “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy”)

“Elizabeth’s ending was so tragic,” Abbott says. “She should’ve at least been recognized and had some semblance of respect postwar. She should have been given proper commendations and more of a monetary award from the North than she got. After the war, when she should’ve gone up North to relax and enjoy the fruits of her labor, she couldn’t sell her house and couldn’t afford to leave Virginia. She got stuck in a place that she fought so hard to save and got no respect.”

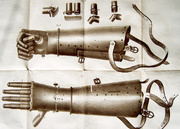

For women—particularly white women in the South—the war forever changed their lives. The men of marrying age went off to war, and 620,000 soldiers on both sides ended up dead, so living as a pampered belle stopped being an option. During the war, women had to manage their farms, defend their homes, and eventually look for work to support their families.

“Women’s activity during the Civil War paved the way for the women’s suffrage movement that picked up steam at the turn of the 20th century,” Abbott says. “The men, the husbands, fiancés, and brothers were gone. The women had been left in charge. Especially in the South, after the war, tens of thousands of women were widowed and tens of thousands more had husbands coming home who were amputees or physically disabled. The women had to become breadwinners and carve out their own lives, different lives from the ones that they had led in their spoiled antebellum years. That paved the way for women to put themselves in the public sphere in a way that they hadn’t before. One of my favorite anecdotes about Elizabeth is every time she paid her property taxes, she included a note of protest that she shouldn’t be paying taxes because she didn’t have the right to vote. She was at the forefront of the feminist movement.”

(To learn more about these female spies and their experiences in the Civil War, pick up Karen Abbott‘s book, “Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War.”)

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums? During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money War and Prosthetics: How Veterans Fought for the Perfect Artificial Limb

War and Prosthetics: How Veterans Fought for the Perfect Artificial Limb History Books“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 2…

History Books“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 2… Civil WarBy the time Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865,…

Civil WarBy the time Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865,… Military and War BooksMilitary memoirs and histories are some of the most treasured possessions f…

Military and War BooksMilitary memoirs and histories are some of the most treasured possessions f… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Makes you wonder how much more of our collective history brave women and the vital contributions they made the largely male historians have overlooked. Though it absolutely not surprising in the least… we’ve been getting the short end of the stick since time immemorial.

…And I really wish this site had an edit option. My grammar isn’t really that bad, I swear.

Fascinating.