If I told you I knew of a middle-aged man who’s devoted to creating a miniature World War II village, you’d probably shrug. It’s a little nerdy, but so what? If I mentioned he was staging elaborate battles with action figures and photographing them, you might think he was a little childish, or possibly an avant-garde artist. But if I put it to you like this: A grown man has spent 14 years building an elaborate imaginary world in his backyard for his collection of Barbie-scale dolls that represent him and his friends, you’d probably be taken aback.

“I think he plays it out over and over again because he’s still trying to rationalize how something like that could happen.”

In America, we have all sorts of rigid boundaries separating what’s considered a healthy interest in miniatures versus an abnormal one, and what’s accepted depends on your gender, your age, and whether you call yourself a “visual artist” or a “hobbyist.” Dolls have long been associated with little girls, so playing with them is assumed to be feminine and frivolous, centered on motherhood, fashion, or vanity. Grown women who seem too enthusiastic about creating miniature worlds are often considered daft. Little boys, meanwhile, are encouraged to act out wild adventures and movie violence, as long as their miniatures are called “action figures.” When they “outgrow” that sort of play, grown men can get away with continuing to meticulously build and paint models of railroads, vehicles, planes, ships, or soldiers, as long as their passion fits neatly into the mature, masculine silo of hobbyist. As for professional artists who manipulate dolls, their artwork is often celebrated for the sly statement it makes—“We know dolls aren’t for serious adults” is part of the joke.

Mark Hogancamp’s photographs of his 1940s doll universe known as Marwencol tear down these arbitrary delineations. His one-sixth-scale world—as explained in the 2010 documentary “Marwencol” directed by Jeff Malmberg and the 2015 book Welcome to Marwencol by Hogancamp and Malmberg’s wife Chris Shellen—serves a higher purpose beyond art, hobby, or child’s play. It’s a means of both physical and mental therapy that’s helping Hogancamp recover from a gender-based hate-crime attack that nearly killed him on April 8, 2000. While his stunningly realistic photos have captured the attention of the art world, Hogancamp’s experience has opened doctors’ and patients’ eyes to the power of imaginative doll play for adults. Now, his story has been optioned by Universal for an upcoming feature film directed by Robert Zemeckis and starring Steve Carell as Hogancamp.

Top: Mark Hogancamp and his alter ego, Hogie, pose with their cameras. Above: “Patton and the Jeep” is one of Mark Hogancamp’s earliest Marwencol photos, taken circa 2004 with a 35mm film camera. (Photos by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

While Hogancamp is being celebrated now, his project wasn’t always so well received. In the early 2000s, motorists who saw him dragging a toy jeep full of dolls down the street would stop to shout “Freak!” out of their car windows. In fact, the gendered taunts he’s received for “playing with dolls” eerily echo the motivations of five men accused of beating him to a pulp outside a bar in his hometown of Kingston, New York: While drinking with a young man he met that night, Hogancamp had confessed that he enjoyed dressing like a woman. The subsequent attack did so much damage to his 38-year-old brain, he completely lost all memory of his adult life and had to re-learn how to walk, speak, and eat.

“Right after the attack, even the people who knew him and cared about him weren’t crazy about the fact that he started playing with dolls,” says Chris Shellen, co-author of Welcome to Marwencol, published by Princeton Architectural Press, and a producer on her husband’s documentary. “His mother told me she was initially not a big fan of Marwencol. It was hard to watch her son, after being beaten nearly to death at 38 years old, have to be a baby again and learn how to take steps and eat. Then, he basically becomes a hermit, playing with dolls in a doll village. It was painful for her. When people started to approach him from an artistic perspective and Jeff and I said to her, ‘We think his stories are amazing and what he’s done is incredible,’ it helped her to see it in a new light, too.”

“He does see his dolls as people because he’s imbued them with souls.”

After the assault, it took 43 days in the hospital before Hogancamp could return to his apartment to try to piece together the clues about his former life. Before the beating, he’d been a Navy veteran and divorcee. He had a gift for drawing, played in punk bands, and found good work building showrooms for trade shows. But he squandered his potential as pent-up anger and alcoholism led to DUIs, a homeless stint, and bouts in rehab.

Eventually, he took a job in the kitchen of a nearby bar and restaurant called the Anchorage. Drinking at home alone after work, he’d put on women’s clothes to feel close to women, whom he was attracted to but felt sure would reject him. In his sketches and diaries, he also engaged in a long-standing fascination with World War II, which came from his maternal grandfather, Papi, a German who’d been conscripted into serving under Hitler and lost his leg in the war. In his estimation of the war, Hogancamp still saw the Allies as the heroes and Hitler’s ardent Nazi followers as the villains, but he also understood the moral dilemma of Germans who were forced to kill or be killed.

When Marwencol is under siege by Nazi SS officers, the village’s men gather at Hogancamp’s Ruined Stocking Catfight Club to strategize using a map drawn by Mark Hogancamp. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

“When Mark was growing up, he was fascinated by Papi’s amputated leg and World War II stories, which gave him a unique view of the conflict that isn’t just about good versus evil,” Shellen says. “To him, it’s more of a gray story.”

In the wake of his attack, Hogancamp realized he didn’t like the depressed, angry man he discovered in his diaries, so he embraced the opportunity to pick and choose the parts of his life he wanted to keep. He decided to jettison the hatred, racism, and shame he saw, and because he didn’t remember the appeal or taste of booze, he opted to never drink alcohol again. But he missed his creative side—the guy who could draw, dance, write stories, and play music. He looked for ways he could start to regain these abilities.

“Mark will see something that’s small and immediately his mind goes, ‘Where can I use that? What part of my village?’”

Wearing stiletto heels, he found, had therapeutic value, helping him regain the balance he needed to relearn how to walk. They also made him happy. “When he saw the high heels in his closet, it wasn’t that he immediately remembered, ‘Oh, I love high heels! I love cross-dressing!’,” Shellen says. “But when he was alone and put his foot in the first heel, it came back to him in a flash. Being able to make it across the street in heels was a huge step in his physical rehabilitation. Now, he wears those tiny, spiked stiletto heels around the house like normal shoes. He says at the end of the day, yes, his feet hurt. But he likes it, because he understands how women feel at the end of the day after they’ve walked around in beautiful shoes.”

In 2002, Hogancamp’s mom moved him into a trailer in rural Kingston, where he rediscovered his interest in World War II miniatures. But his shaky hands couldn’t manipulate the 1:36 scale figures he’d worked with before. His friends Janet and Mark Wikane, of J&J’s Hobbies in Kingston, suggested he try working at 1:6 scale, which is the size of 12-inch-tall figures like Barbies and the original G.I. Joes. He found an American 82nd Airborne Pathfinder by Dragon Models Limited who looked like him and named him Captain Mark “Hogie” Hogancamp. At the time, he had also made friends with two supportive women—a waitress named Wendy at the Anchorage, which gave him a couple of hours of weekly work after the attack, as well as a neighbor named Colleen. They were both married, but he felt inspired by his crushes on them and found two Barbies to represent them. Then he acquired a James Bond Pussy Galore figure that looked just like his mom. Slowly, he accumulated more Barbies, as well as action figures by Dragon Models Limited, Ultimate Soldier, and Blue Box International.

Eventually, Mark Hogancamp regained his ability to work with 1:36 scale figures, which let his alter ego Hogie adopt his miniature hobby. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

Dressing the dolls was a physical challenge that helped him relearn how to work with his hands. Creating characters for them, usually inspired by friends, sparked his imagination, but now he had a bunch of personalities with no place to go. So he collected some scraps of plywood in his backyard and built a tavern called Hogancamp’s Ruined Stocking Catfight Club, a watering hole he dreams of opening in real life, which would offer staged catfight entertainment somewhere between burlesque and pro wrestling. After he erected the Catfight Club, he built miniature businesses for his crushes, a restaurant called Wendy Lee’s Kitchen for Wendy and a store called Pocket Full of Posies for Colleen. And he named the town, an imaginary village in World War II-era Belgium, Marwencol, for “Mark, Wendy, and Colleen.” People of all nationalities—American, British, Italian, Canadian, German, Belgian, Russian—congregate in this mysterious village to enjoy staged catfights and camaraderie, the only enemies being the Nazi Waffen-SS who linger outside Marwencol looking for opportunities to pounce.

“Mark absolutely did not build Marwencol to make ‘Art,’” Shellen says. “Before his attack, he’d been painting these tiny models from World War II and Vietnam. After the attack, he just didn’t have the dexterity to work with those models. Moving on to larger figures, he began with the doll that became Hogie, his alter ego. He worked on aging it and putting the clothes on and off of it. He intuitively realized that working with these figures was doing some good for his dexterity. Once he started creating storylines for them, it helped him remember things and work through some of his anger issues.

“A lot of senses have been involved in getting Mark’s memories back, and that’s been a theme throughout his recovery,” Shellen says. “Brain specialists, who try to help people restore memories and rebuild connections, have been particularly interested in Mark’s story.”

The role of dolls and imaginative play in Hogancamp’s recovery is at odds with the ways dolls, particularly Barbies and their ilk, have been dismissed in our culture. “Friends of mine who are mothers are actively trying to keep Barbie dolls out of their daughter’s hands,” Shellen says. “I think that’s a shame because little girls, by and large, don’t play with a doll because they’re only thinking, ‘I love her fashion’ or ‘Oh, she’s so pretty.’ Most of the time, they use the dolls as characters in little dramas that they’ve created. It’s their way of making sense of the world and figuring out social interaction and solving conflicts.

Hogie and Anna get married with the bodies of the five SS officers strung up behind them. (Photo by Mark Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

“We’ve said ‘That’s a girly thing, and it shouldn’t be for boys,’” she continues. “Now we’re taking it out of the hands of girls, too, thanks to the idea that doll play is somehow babyish or teaching them the wrong message. But I completely disagree. Creating imaginary worlds through doll play is the same as a writer or narrative filmmaker using fictional characters, or an artist hiring a model.”

“A doll, like Anna, always has the exact same expression. But when you look at his photos, that expression changes from resolution to dislike to love to confusion, depending on the context.”

Marwencol lets Hogancamp grapple with the horrors of his attack, which he doesn’t consciously remember. But his village is tormented by five evil SS officers, who repeatedly stalk and brutalize Hogie, much in the same manner his five alleged attackers did. And the tough but feminine women of Marwencol—including Hogie’s girlfriend, Russian princess Anna Romanov, and his thwarted lover, Deja Thoris, a Belgian witch—always save the day, much like the Kingston bartender Nora Noonan, who found Hogancamp bleeding to death outside the Luny Tune Saloon in 2000 and got him to the hospital minutes before the blood filling up his lungs drowned him.

“Mark makes a big point that women always rescue Hogie in Marwencol,” Shellen says. “In his life, he feels like men kicked him out of the club for being a cross-dresser and women took him in. In Marwencol, women are always in charge and always wind up saving the day.”

After the attack in 2000, local detectives and the Ulster County assistant district attorney Emmanuel Nneji weren’t able to find enough hard evidence for a hate-crime prosecution, but they were able to charge his attackers with gang violence. Freddy Hommel—the 23-year-old who initially made friends with Hogancamp at the bar, got angered by Hogancamp’s cross-dressing habit, and started the attack—claimed he didn’t really hurt Hogancamp in the fight and was sentenced to five years in prison. Hommel’s friend 21-year-old Richard Purcell, who stomped on Hogancamp’s head repeatedly, received a nine-year sentence. A 16-year-old minor known as “Black Freddy” pled guilty to all charges and received a reduced five-year sentence. Two other alleged assailants, David Mead, 19, and Noah Rand, 21, insisted they didn’t touch Hogancamp and only received five years probation. By 2010, all of Hogancamp’s accused attackers were free and wandering the streets of Kingston, an upstate New York town of almost 24,000. In 2013, Hommel died at 36 from an illness.

Five SS officers sneak up and attack Hogie, punching and kicking his head. This image is eerily similar to the beating Mark Hogancamp endured but can’t remember. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

“It’s got to be strange to have these people who nearly killed you still living in the same town,” Shellen says. “Kingston is big enough, fortunately, that Mark’s never run into them. But a friend of his once wound up on a job with one of the attackers. The attacker was talking flippantly about why he’d been in jail and clearly has no remorse.”

That’s probably the reason that, in Marwencol, evil never dies. The five vicious SS officers that have it in for Captain Hogancamp have the superpower to respawn and come back to life even after they’ve been brutally murdered by the women of Marwencol. They come after Hogie again and again.

“He’ll flick red nail polish on to the dolls’ faces, too, so he gets a realistic blood splatter. The result is gruesome, but I think it’s gorgeous, too.”

“When we were making the film, my husband, Jeff, had Mark return to the attack scene and Mark said, ‘I don’t remember what happened,’” Shellen says. “But we found the records of the attack at the DA’s office and realized he had maneuvered these dolls in a way that’s almost identical to what happened to him. I think he plays it out over and over again because he’s still trying to rationalize how something like that could happen. The act of going through it and then having his character survive is cathartic.”

Back in 2002, when Hogancamp told his friends at the Anchorage about their alter egos’ adventures in his doll world, they didn’t believe him, so he started snapping photos using an old 35mm film camera. His friends were so impressed Hogancamp felt emboldened to send a few snapshots to an Ultimate Soldier fan page, and he even won a contest on the site, for a 2004 image called “Rescuing the Major,” which depicted his brother Mike’s doll alter ego saving a wounded officer amid a Waffen-SS assault.

The image was so realistic that in 2015, a conservative Facebook user named Terry Coffey searched for an image of World War II heroism and posted “Rescuing the Major” as a counterpoint to Caitlyn Jenner’s decision to come out as a woman in June of last year: “As I see post after post about Bruce Jenner’s transition to a woman, and I hear words like bravery, heroism and courage, just thought I’d remind all of us what real courage, heroism and bravery looks like!” Coffey’s post quickly went viral, and the irony of selecting a picture of dolls taken by a man who was viciously beaten for being a cross-dresser came back to him. To his credit, Coffey admitted his mistake and denounced the hate crime against Hogancamp and hostility toward Jenner.

Hogancamp’s 2004 photo, “Rescuing the Major,” won the Ultimate Soldier contest and has been mistaken for a real World War II image on multiple occasions. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

About a decade before Coffey stumbled upon Hogancamp’s photo, the New York City art world discovered him and began to celebrate his one-of-a-kind work. First on the Hogencamp trail was then-Kingston-based photographer David Naugle, who spotted Hogancamp around town in early 2005. Hogancamp stood out because he’d usually be wearing one of the American G.I. uniforms he’s collected and sometimes pulling a toy jeep full of dolls down the road. After Naugle worked up the courage to introduce himself, Hogancamp was happy to share an envelope full of his Marwencol prints. Blown away, Naugle took them to Tod Lippy, who edits a New York City nonprofit arts magazine called “Esopus.” Lippy and Naugle got Hogancamp’s permission to collaborate on a piece about Marwencol, which ran in the fall 2005 edition of the magazine.

“Creating imaginary worlds through doll play is the same as a writer or narrative filmmaker using fictional characters, or an artist hiring a model.”

Around that time, Hogancamps’s old Pentax camera gave out, and his mother bought him a digital 7.1 megapixel Canon G6. “She was a wonderful mother like that,” Shellen says. “She didn’t fully understand Marwencol, but she saw it meant something to Mark. She bought that camera long before she understood what the town was about or had any sort of appreciation for it.”

At first, Hogancamp was befuddled and frustrated by this strange device, but once he figured out how to use it, it empowered him to capture more pictures of Marwencol that matched the images in his head. The flip-out viewer helped him as he got doll-level in the dirt to snap shots from their perspective. Creating digital files freed him from the limitations of film photography—taking only two-dozen photos in one session, sending them to the processor, and waiting two weeks to see if they came out any good. Depicting his vision perfectly was now within reach.

Meanwhile, the “Esopus” piece drew all sorts of attention to Hogancamp’s photography. Initially, Hogancamp was reluctant to invite the outside world to gawk at his intensely personal fantasy realm, but he concluded it might help other people like him, people who have suffered from brain damage or PTSD. The article caught the eye of Shellen’s future husband Jeff Malmberg, who started working on his documentary, and Manhattan’s White Columns gallery debuted Hogancamp’s photos at a 2006 show. Before long, Marwencol was featured on Showtime’s “This American Life,” and Kingston’s One Mile Gallery approached Hogancamp about representing him as an artist. The guy once derided as a “freak” by locals became celebrated by people around the world, who continue to donate dolls, model vehicles, and other props to his ongoing saga.

Hogie receives new figures for his miniature World War II town in the mail. (Photo by Mark Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

What’s incredible about Hogancamp’s photos is how these dolls seem to express the emotion of the moment. For Welcome to Marwencol, Shellen and Hogancamp arranged his photos in a comic-book format to tell part of the cinema-like story he’s invented.

“A doll, like Anna, always has the exact same expression,” Shellen says. “But when you look at the stories in the book, that expression changes from resolution to dislike to love at first sight to confusion, depending on the context of the photos.” While to outsiders Barbies may look blank-expressioned compared with complex faces of the specialized action figures, Hogancamp sees each of his fashion dolls as an individual, too. “He told us once, ‘You know, Barbies all look different,” Shellen says. “Every Barbie comes off the line with slight alterations in her eye spacing and details like that, so they’re all unique as well. He’s protective of all his figures.”

“The people who’ve approached Mark have connected with different parts of his story—they’re people who’ve been victims of an attack, people who’ve been victims of gender-based hate crimes, and people who’ve suffered brain injuries.”

That’s because Hogancamp has endowed each of his dolls—at least the main characters—with such strong personalities that they’ve come alive in his mind. Before he does a shoot, he sits with the dolls, thinks about their personalities, and lets that dictate the story he tells.

“He does see his dolls as people because he’s imbued them with souls,” Shellen says. “Other artists do amazing work taking shots of miniature trains or dolls. Most of them are either trying to be ironic or they’re trying to create something magnificent. For example, another artist re-creates incredibly realistic battle scenes with the same dolls that Mark uses, and his work is gorgeous. But it doesn’t have the same dimension. When Mark sets up soldiers, he’s not thinking, ‘This looks just like that battle.’ He’s thinking, ‘Fritz over there, he’s having a problem with Johnny, and so they’re going to look at each other in the background like they’re not happy with each other.’ In his mind, there’s actual drama happening here, and it’s very deep and layered.”

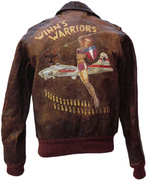

Thanks to his long obsession with the World War II era, Hogancamp has absorbed details from reading history books, watching the History Channel, 1940s films, and collecting WWII regalia and models. He’s so familiar with the period that he’ll get little details just so. For example, Hogie’s bomber jacket has a “blood chit” sewn on the back—a piece of fabric printed with American and other flags as well as Chinese text, meant to identify a downed pilot as friendly to civilians. Hogancamp puts in the work to ensure his photos look authentic down the smallest detail, which is why he’s so often seen dragging a toy jeep down the road—he’s wearing down the vehicle’s tires.

“He’s fully committed to the image that’s in his head,” Shellen says. “Somebody bought him a model plane, for instance, and the plane was beautiful and perfectly painted, as if it just rolled off the assembly line. Because he was in the Navy and he has an amazing eye for detail, Mark knows how metal rusts and gets weathered by wind. So he took out these rust-colored and metallic paints and weathered the plane to the point where it looks authentically used.

The cover of Welcome to Marwencol shows how Mark Hogancamp weathers his model airplanes. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

“It’s the same thing with the dolls,” she continues. “He says if you put a doll in a new, starched coat, it looks like a doll. So he’ll put the uniforms on the new dolls, and then he’ll leave them in the elements so that they get soaked in the rain and caked in mud. Then the clothing falls properly, and it looks dirty, like it would. He’ll also use the dirt outside to give the dolls’ faces natural contours, so they look a little haggard. He’s meticulous about the hair as well. He’ll actually style the women’s hair so it doesn’t stick out like doll’s hair sometimes does.”

Hogancamp’s gifts extend to posing the dolls so they appear to come alive for the photographs. “When I stand a doll up, I could spend an hour trying to get a real pose, and it will still look like a doll,” Shellen says. “Mark just wraps his hands around the doll and manipulates it, almost like a chiropractor. He shifts it just a little bit, and all of a sudden, you can see how the doll is bearing weight and you can see that its arm is at a natural angle. He’s got an amazing eye for body language that very few people have.”

“In his life, he feels like men kicked him out of the club and women took him in. In Marwencol, women are always in charge and always wind up saving the day.”

Despite Hogancamp’s obsession with period-correct realism, his story is also very much a fantasy with magical elements to it. Deja Thoris, the blue-haired Witch of Marwencol, has a “time-displacement machine,” which Hogancamp built after a VCR ate his favorite porn tape. He opened up the machine and decided it looked like a magical mechanical box that Deja could use, Shellen explains. Inside, he installed a cell-phone holder for her seat. The time-displacement machine allows him to reset his story as many times as he wants. But generally, Deja falls in love with Hogie, he meets Anna and falls in love with her, and Deja ends up thwarted and angry. The SS officers, who have the supernatural ability to respawn, can only be killed when Deja sends them to another dimension, where they meet the fearsome Knight of Marwencol, who swiftly chops off their heads. Marwencol itself exists in another dimension, where it’s perpetually the early 1940s in Belgium, protected from the modern world by the transparent Dome of Marwencol. Occasionally, doll-people and stories from 2016 can pass through the dome into Marwencol, and Hogancamp himself exists on the periphery as the Giant of Marwencol.

“He went through a phase for a while where he was really into the One Sixth Warrior Forum,” Shellen says. “Most of his buddies from that web page have characters in Marwencol, and for a year and a half or so, all the storylines were based on them, like one of them would go fishing. It was a very sedate year in Marwencol. Then he’ll go through periods where he gets inspired by history that he’s reading about and stage a lot of historical re-creations. He’s influenced by pop culture and news, too, so when Obama got elected, the president briefly got a character in Marwencol. It’s probably a good thing that Mark’s rage died down, and he doesn’t feel it all the time. If he does feel it, then Marwencol’s there and he can enact a battle or something violent. But if it’s peacetime for Mark, it’s peacetime for Marwencol.”

Because he started off with so few resources, Hogancamp has an eye for waste that can be turned into Marwencol treasures. Broken windshield glass lying on the side of the road became ice for his doll’s cocktails. His neighbor’s remodeling waste pile provided scraps of wood, tiles, and roof shingles that he used to construct Marwencol buildings. Postage stamps and magazine scraps become wall art. “Mark will see something that’s small and immediately his mind goes, ‘Where can I use that? What part of my village?’,” Shellen explains.

Hogie “draws” Anna’s portrait for her in his diary. His sketchbook is about the size of a postage stamp. (Photo by Mark Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

As his dexterity has improved, Hogancamp has started to work with 1:36 scale figures again, allowing his 1:6 alter-ego, Hogie, to adopt Hogancamp’s hobby of creating stories with dolls and photographing the action. Hogancamp’s also regained his drawing ability enough to produce hundreds of tiny documents for his characters and buildings—thumbnail-sized wartime notices, propaganda posters, maps, magazines, and even sketchpad drawings, such as the tiny portrait of Anna that Hogie is supposed to have drawn.

“Every time one of his characters needs a map of Marwencol, inevitably, he can’t find one because they’re all in other characters’ briefcases, so he’ll draw a new one,” Shellen says. “I wish that I had done a photo study of the contents all of his characters’ bags and briefcases because they’re full of whatever that character needs. If someone is supposed to be in charge of explosives, they’ve got a bag containing the accurate contents for that role: It’s full of grenades, smokes, maybe a book that that character’s reading, and the map they’re going to be using. He’s collected all of these things and filled their bags so that they’re prepared wherever they go. Rarely does he open the bags. He just does that for the characters.”

At this point, Hogancamp has accumulated more than 200 action figures and dolls, which mostly live in stacked in boxes in his trailer. Some figures he’s assigned distinct characters, while others play various roles in the background, like movie extras. The only way Mark will fully retire a doll is if it’s been beheaded by the Knight of Marwencol; that figure is buried, never to return.

“He’ll reuse dolls over and over again,” Shellen says. “If a doll has been given a specific character—like for instance, Anna—it will always be that character. If Anna dies, she’ll just come back as Anna. For a while, Anna had a bodyguard who was also Anna, and you could tell the difference between them by their necklaces. But if a doll is a soldier in the background or a cop who is coming in from the present day, that’s like a movie extra. So if he dies, he will pop up again—maybe next time as a Nazi.”

Mark Hogancamp disfigures and paints his dolls to create grisly gunshot wounds. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

Hogancamp isn’t afraid to warp and damage his action figures in the name of telling his story. Creating realistic pools of blood and ghastly wounds are a part of the violence he wants to depict.

“For blood, he’ll often use nail polish because it looks realistically shiny, and he can leave it on them for a long time,” Shellen says. “He’ll flick red nail polish on to the dolls’ faces, too, so he gets a realistic blood splatter. He also makes fake blood, a sugary red solution, and for one particular massacre scene, he splattered that all over the snow around the people and laid the bodies on top of each other in a pattern that’s realistic to how the soldiers would have fallen. When bullets hit a vehicle, he heats up the end of a pen or something metal and pushes it through the windshield and jeep sides. He’s meticulous about figuring out where the bullet spray would happen. To create deeper flesh wounds, he’ll heat up a pen again and press it into the doll’s head and then use red fingernail polish and model paints, too. The result is gruesomely realistic, but I think it’s gorgeous, too.”

“It’s probably a good thing that Mark’s rage died down, and he doesn’t feel it all the time. If it’s peacetime for Mark, it’s peacetime for Marwencol.”

Shellen says it’s been a pleasure watching Hogancamp come out of his shell. Going to New York City for his 2006 White Columns exhibition wracked his nerves, but he got a positive reception. When the “Marwencol” documentary premiered in 2010, he was a little less nervous, and then he walked out onstage in high heels to thunderous applause and cheers. And he’s gotten to see the real impact of his work on his fans.

“The people who’ve approached Mark have connected with different parts of his story—they’re people who’ve been victims of an attack, people who’ve been victims of gender-based hate crimes, and people who’ve suffered brain injuries,” Shellen says. “Doctors will tell brain-injury victims that they have a year or two to recover all of their cognitive and physical abilities. His story has helped the victims realize that if they put long-term effort into their recovery, they could continue to get better. It’s been a decade, and Mark continues to improve every time we see him.

“It’s always strange when you go from anonymity to people approaching you on the street and saying they love you,” she continues. “A couple of people have shown up at his doorstep, which can be unsettling, too. But for the most part, people who approach him are grateful for his story. They have a personal connection to it because they’re getting over something themselves, or they feel for him, or they like his work. In Kingston, he was just that weird guy who walked around dragging a toy jeep. After the film came out, the people around him had a bigger appreciation for him, or at least understood where it was coming from. He gets a lot more respect there now.”

Deja Thoris, the Belgian Witch of Marwencol, marries the Giant of Marwencol, a.k.a. human Mark Hogancamp, at the village church. (Photo by Hogancamp, courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press)

The respect Hogancamp has earned has created a space where he can be himself with all his eccentricities, including being “married” to one of his dolls. Human Mark Hogancamp a.k.a. the Giant of Marwencol felt so bad for Deja Thoris and her unrequited love for doll Captain Mark “Hogie” Hogancamp that he married her in Marwencol and carries her everywhere he goes in a specially made pouch that hangs around his neck.

“If you see Mark, you’ll see Deja,” Shellen says. “She’s been a crucial figure in his life. You know how when most of us get upset, we have that voice in the back of our heads—maybe it’s our mom or our therapist or a wise sage—who says, ‘It’s OK; this is going to pass’? Deja is that person for him. When he gets upset about something, Deja helps him think through it. He cut back on smoking a little bit because Deja told him, ‘I need you to live because if you don’t live, I don’t live.’ She’s been a positive force for him. The Giant married her in Marwencol because he fell in love with her and he felt terrible that she had this unrequited love for Hogie and Hogie constantly left her for Anna. But in the real world, I think Mark married Deja because she is his perfect counterpart.”

Just before Hogancamp’s mother passed away in 2010, she asked the documentarians, Shellen and her husband, Jeff Malmberg, to look after her son. Even though they live in California, on the other side of the country from Kingston, they talk to Hogancamp on the phone on a regular basis and receive emails with his latest digital images of Marwencol.

“Mark is very kind and sweet,” Shellen says. “He had a horrible thing happen to him and I think he would be the first to say that he wasn’t the best, nicest guy before the attack. But he took the chance to reform himself afterward, and he’s just a lovely human being. He’s doing so well considering the circumstances he was dealt.”

(To learn more about Mark Hogancamp and Marwencol, visit his web site, watch Jeff Malmberg’s “Marwencol” documentary, or pick up Hogancamp and Chris Shellen’s book, “Welcome to Marwencol,” published by Princeton Architectural Press.)

Baby's First Butcher Shop, Circa 1900

Baby's First Butcher Shop, Circa 1900

Guys and Dolls: Veteran Toy Designer Wrestles With the Industry's Gender Divide

Guys and Dolls: Veteran Toy Designer Wrestles With the Industry's Gender Divide Baby's First Butcher Shop, Circa 1900

Baby's First Butcher Shop, Circa 1900 WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Barbie DollsLaunched at the American Toy Fair on March 9, 1959, Barbie was an 11.5-inch…

Barbie DollsLaunched at the American Toy Fair on March 9, 1959, Barbie was an 11.5-inch… World War TwoThe events and battles of World War II played out on every continent of the…

World War TwoThe events and battles of World War II played out on every continent of the… Action FiguresThe concept of an "action figure" was introduced in 1964, when G.I. Joe hit…

Action FiguresThe concept of an "action figure" was introduced in 1964, when G.I. Joe hit… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I think this is the coolest thing ever! And I’m 40.

I love this, I also work with dolls.

This is a cool article Lisa ! Well done and I was not aware Mark Hogancamp’s passion even though it is a bit to graphic with creating the violence he saw for me it seems that is was good therapy for him .

I’m 72. The strength of the human spirit is incredible. The gutless punks who attempted to extinguish it will have to live in a world that admires what this man has accomplished and disdains their act of cowardice.

Wow! Incredible! Does he allow tourists to see this collection?