Firecrackers are essentially un-American, even though we associate them with our most deeply patriotic celebration, the Fourth of July. The fact is that firecrackers are foreign-born novelties, and have been as long as Americans have lit them for a noisy salute to the nation’s birth. As it turns out, firecracker history is as colorful and complicated as the lithographed artwork used to sell them. Warren Dotz, a pop-culture historian, collector, and author of many books, including a pair on cat and dog food labels, spoke with us about their story.

After firecrackers became a staple of July Fourth events, gun- and anvil-shooting were deemed too dangerous.

Dotz says that, growing up in New York City, he and his friends were obsessed with firecrackers. In a 2009 interview with Marty Weill at Ephemera, he explained, “The day after the Fourth of July my friends and I would search to salvage the gunpowder in those firecracker ‘duds’ that hadn’t exploded. I also went looking for the black and yellow Black Cat brand and the sky-blue Anchor brand labels that hadn’t been blown to smithereens. Years later, I would see these labels, as well as even more spectacular labels, at collectible fairs and flea markets and decided that I would tell their story.”

Here are 10 things we learned about firecrackers and their labels from talking to Dotz and reading his Ten Speed Press trade book Firecrackers: The Art & History, published in 2000 and co-authored by Jack Mingo and George Moyer.

1. Firecrackers were invented by the ancient Chinese, who discovered naturally exploding bamboo.

“Because firecrackers have become icons of American popular culture. we often forget that they are thousand-year-old ceremonial items that originated in Asia,” Dotz says. “The first firecrackers were completely organic and probably accidental.”

Green bamboo segments are full of air and sap that will expand when heated, as the fire erodes the woody exterior, causing it to blow up. Dotz suspects this was discovered by accident, when a person was looking for fuel for a fire. Exploding bamboo became a tradition in Chinese Lunar New Year ceremonies, intended to scare away evil spirits. Crude versions of gunpowder derived from sulfur were developed and used in firecrackers in the 7th century, and firecrackers evolved as paper tubes replaced bamboo and saltpeter, also known as potassium nitrate, came to dominate the mix. While the Chinese thought to use gunpowder in warfare for flamethrowers and grenades, it wasn’t until it landed in Europe in the 13th century that people thought to use it to fire projectiles from canons and guns. Chinese gunpowder, hence, gave Europeans the power to colonize parts of China.

2. Firecrackers were not used in the earliest Fourth of July celebrations, as they hadn’t been exported to America yet.

“Interestingly, firecrackers were reported to have been part of Fourth of July celebrations only after the holiday’s 11th year,” Dotz says. “The norm before then was ‘illuminations’—where people placed candles in their windows—as well as bonfires, bells, musket fire, and loud parades.”

Also, the earliest Fourth of July celebrations involved using explosives to send anvils into the air. According to Firecrackers, “A blacksmith’s anvil was placed on the ground and a bag of gunpowder with a fuse was placed on top of it. Finally, another anvil was placed upside down on top of the bag, the fuse was lit, and everybody scattered. This was to avoid being crushed like a cartoon character, because the top anvil was propelled into the air before returning heavily to the ground. It was said you could hear the sound of a good anvil shoot for miles in all directions.”

In 1787, a shipping merchant named Elias Haskett Derby brought a few boxes of firecrackers to America on a cargo ship from China, and he sold out immediately. After that, they became a staple of Independence Day celebrations, as gun- and anvil-shooting were deemed too dangerous for family events.

3. In the South, where the politicians and plantation owners believed that states should hold all the power, Fourth of July was not a big holiday until the 1930s.

There, firecrackers were used to celebrate Christmas between the 1830s and 1930s.They were particularly popular with the enslaved African Americans, who got Christmas off and used whatever change they could scrounge up to buy them. If they couldn’t afford firecrackers, enslaved people would fill pig bladders up with air, tie them closed, and then throw them on the fire so they’d pop. It’s possible that plantation owners were reluctant to encourage the celebration of Independence Day, which lauds overthrowing the people in power. And they definitely wanted to encourage their enslaved populations to put their faith in Jesus, who would free them only in the afterlife. This is probably why, in a vintage firecracker-label collection, you’ll see images of Santa Claus, as well as racist caricatures of African Americans and even slurs about poor white people, like “Geo’gia Crackers.”

4. Manufacturing firecrackers has never been a viable business in the United States.

Firecracker making has always been dangerous work, but in the 19th century, it was done on a relatively small scale, made in Chinese homes and shops by the whole family—mom, dad, and the kids. They’d braid chains of 16-50 for white Americans and links of 1,500-5,000 for Asian Americans, who set them off all at once for Lunar New Year. Firecrackers from numerous small makers would be purchased by big importers like Hitts Fireworks Company in Seattle. Chinese families would work 17 hours a day, seven days a week, for a measly 7 cents a day. There was no way American plants could compete with their price and productivity. In the 1910s, British-born Seattle businessman William E. Priestley of Hitts built the first Chinese firecracker factory in Canton, and it wasn’t long before the factory caught on fire, killing 30 female workers. Hitts paid each family $30 in damages. Today, Chinese firecracker factory workers get paid 80 cents to $1 a day. More colorful and complicated fireworks, meanwhile, have always had a much higher profit margin, and are sometimes made in the United States or Europe.

5. Since firecrackers are virtually indistinguishable from one another, makers got really creative with the labels.

In the late 19th century, wooden boxes that contained firecrackers would come with a beautifully embossed and hand-painted gold-leaf label, which was also used for a store display, but the individual firecracker chains themselves would be wrapped in plain red paper. But after a shipment of lithography machines arrived in China in the 1910s, glue-on paper labels became an important tool to convince American boys to spend their spare pennies on paper-wrapped “bricks” (usually 5 to 10 cents apiece). “Because firecrackers were so inexpensive to produce, competition for the export markets was fierce among manufacturers who essentially had indistinguishable products to peddle,” Dotz says. “Product packaging became a crucial component to capturing and keeping customers.”

“Because firecrackers have become icons of American popular culture, we forget that they are thousand-year-old Asian ceremonial items.”

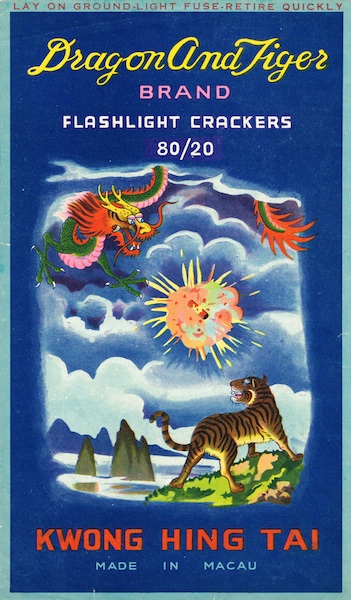

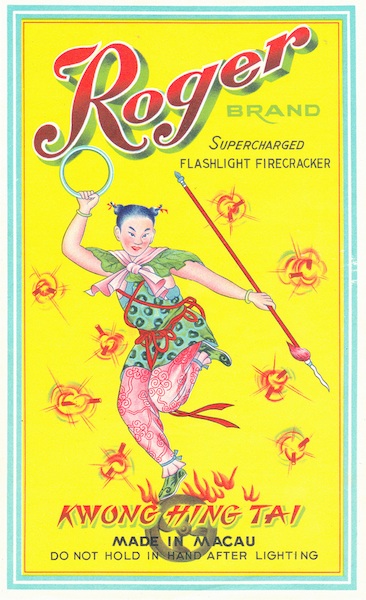

The first labels often referred to ancient Chinese myths that Americans didn’t understand but found exotic and exciting, including dragons (protecting humanity from evil), tigers (driving off demons), respected warriors, as well as mythological figures like No Cha, Weaving Maiden, and Moon Maiden. Some labels were more like slice-of-Chinese-life postcard scenes. And since animals were always auspicious symbols in Chinese culture, pretty much every animal you can imagine was featured on a firecracker label, the most popular brands being Zebra, Giraffe, Camel, and Black Cat. “Black cats are considered good luck in China but bad luck in the America,” Dotz says. “As the famous brand name of Li & Fung, the Black Cat label has lived out nine lives as probably the longest-surviving brand of all.”

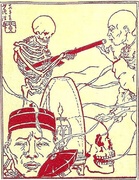

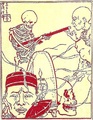

As the century progressed, American pop culture was also reflected in these labels, with figures like Daniel Boone, Captain Kidd, Robinson Crusoe, Tarzan, cowboys, King Kong, werewolves, and giants, as well as sports and military imagery and caricatures of African Americans and Native Americans. In the 1950s, the Space Age influenced optimistic labels of rockets, fantastic depictions of flying saucers, and nightmarish images of Atomic bombs. “During the years of cowboy movies and the early days of television, ‘Old West’ motifs were popular as firecracker artwork was aimed squarely at the heart of the American market with brand such as Cowboy, Buck-a-roo, Bronco, Western Boy,” Dotz says.

6. “Carefully take apart an old firecracker, and you might find a bit of news, comics, society columns, or even an old paperback novel from a half-century ago,” according to Firecrackers.

Paper has long been a principal material in the manufacturing of firecrackers, but factories in early 20th century China had a difficult time finding enough paper to meet the both the local and export demands for firecrackers. Priestley came up with the idea of newspaper recycling drives in the 1920s. In America, Boy Scouts and churches would raise money by going door-to-door asking for old newspapers and then selling them to a used-paper merchant. The newspapers would then head to China on empty cargo ships that had unloaded all their goods in the United States. These drives lasted into the 1970s.

7. As brighter, more colorful fireworks like Vesuvius Cones and Roman Candles developed in the 20th century, exploding firecrackers became passé and needed more “flash.”

In 1916, an engineer working for Hitts Fireworks Company in Seattle had the idea to add the flash powder (then used in flash photography) to the mix. The key ingredient in flash powder was aluminum, and when the new “flashlight firecrackers” or “flash crackers” exploded, they gave off a bright light and had a stronger report. (No, if you see “flashlight” on a firecracker package, it does not mean “Hold this in your hand to see in the dark.”) Unfortunately, this new technology made the gunpowder mix even more dangerous for Chinese workers to make, and caused the big fire that killed 30 workers at Priestley’s factory.

8. Firecracker fanatics often make pilgrimages to Macau to see the shut-down factories of former firecracker companies like Kwan Yick, Yick Loong, Po Sing, and Kwong Hing Tai.

In 1912, the reign of emperors collapsed in China, and a growing anti-foreigner sentiment made things difficult for American and European firecracker-factory owners. Even Chinese-owned companies like Li & Fung—which exported famous brands like Giraffe and Black Cat to the United States—felt the pressure. Li & Fung moved to British-controlled Hong Kong, while Priestley moved his factory to Portuguese-controlled Macau in 1925. Even though Macau was becoming the firecracker capital, Li & Fung returned its operations to mainland China in 1930s, only to see them occupied by the Japanese Army during World War II. U.S. trade sanctions during the Korean War forced Li & Fung to open a plant in Macau, where it was one of six manufacturers allowed to export fireworks. (Eventually, Li & Fung took over the operations of the five other companies.) In 1972, President Nixon lifted the trade embargo on China, and suddenly mainland China, which had more natural resources and government-subsidized workers, became the more profitable spot to make firecrackers.

“Within two years, mainland Chinese firecrackers took over the market,” Dotz says. “Macau now only has the architectural vestiges of their famous firecracker manufacturing history in the form of old shipping facilities on their wharves.”

9. Rants against firecrackers killing or maiming children have happened since their invention, and now, they’re banned in 18 states.

In a 1875, a “Chicago Tribune” editorial complained that Chinese firecrackers had killed small boys, put out eyes, rended limbs, scared horses, and burned down houses since they were introduced to July Fourth celebrations. A 1952 “Saturday Evening Post” editorial complained that fireworks had killed and wounded 11 times more Americans than the Revolutionary War itself in just 52 years. These concerns have prompted legal regulations about what kind of firecrackers can be sold. The amount of flash powder allowed was lowered to 50 milligrams; “safety fuses” that are hard to light anywhere but the end were invented; braids got harder to undo; and potassium chlorate and sulfur were removed from the flash powder mix, making the firecrackers less strong. Cherry bombs and M-80s became felony-class explosives in 1967. Outside of the 18 states that have banned firecrackers, most United States municipalities have ordinances banning fireworks within city limits. Even though these laws have made firecrackers more uniform (most are 1 ½ inches long, while “ladyfinger” crackers are ⅞ inches long), they’ve also become more exciting as contraband material that a majority of Americans buy anyway.

10. Firecracker collectors date their labels based on seven “classes.”

This is somewhat confusing because the Interstate Commerce Commission also labels firecrackers as Class C explosives. Regarding dates, Class 1 firecracker labels, those made before 1950, have no government-regulated safety warned, but simply say “Made in China” (and less commonly Canton or Hong Kong). Class 2, 1950-1954, still have no safety warnings, but now say “Made in Macau” or “Made in Portuguese Macau.” Class 3, 1955-1968, have an additional marking “ICC Class C.” Class 4, 1969-1972, have two warnings, “Caution: Explosive” and “Lay on ground, light fuse, get away.” In 1973, Congress shifted the responsibility of grading fireworks to the Department of Transportation, so now Class 5 labels, from 1973-1976, read, “DOT Class C Common Fireworks” and “Made in China” again. Class 6 labels, 1977-1994, are the same as Class 5, except they also say “Contains less than 50mg flash powder, as per new government regulations.” Class 7, 1995-present, has a new mark referring to an international standard for hazardous material, “UN 0336, 1.4g consumer fireworks.”

(All the facts above come from Warren Dotz and his 2000 Ten Speed Press trade book “Firecrackers: The Art and History,” co-authored with Jack Mingo and George Moyer. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets

Guts and Gumption: Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Wore Their Hearts on Their Helmets How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci…

AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci… PaperBefore the Internet reduced all correspondence and information to colorless…

PaperBefore the Internet reduced all correspondence and information to colorless… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Lisa,

Remember how you, Dad and John set that field behind our fireworks stand on fire shooting off fireworks? Fun times!

Awesome read, and the flickr channel is well worth visiting – full of awesome firework labels :)

Really cool article about the history of firecrackers, but why couch it in in-Americanness? Much of what America has adopted as its own isn’t American in origin: the national flag dirrives from the Washington family coat of arms, apple pie isn’t an American invention nor is basketball which was invented in Canada. Even the dominant language and religion come from Europe. In fact, America is UNAMERICAN and wasn’t America until European settlers arrived to clam it as their own. The history of fireworks and their origins in America is interesting, but is the angle on fireworks being unamerican relevant?

James Naismith was Canadian but he invented basketball in Springfield, Massachusetts. Gridiron football could claim a Canadian origin though, since one of the pivotal rule changes that turned rugby football into gridiron came about during a game between Toronto and Harvard, in Toronto. The two teams played by different rules and during a pre-game conference to establish a common set, the forward pass was accidentally allowed. It wasn’t the first time football had been played with forward passes allowed but it was a lasting change this time: the fans loved it.

Sorry, but firecrackers have been made in the us for several years until resently. Hitt made them and several other companies.

Fascinating read! The artwork alone says so much about who we are as people. I’m new to the deep south in Austin, Texas and just this little gem of perspective about how the south viewed 4th of July is deeply interesting.

My mom took me to Chinatown in NYC for the New Year celebration. While we were watching the parade, someone handed me a lit firecracker to throw. But my immature timing was off, and it exploded in my tiny hand. Screaming, my mom rushed me into a nearby Chinese apothecary, resplendent with mystical roots and herbs. The owner sighed, pulled out a can of Solarcaine from under the counter, and sprayed my hand. The miracles of ancient medicine!

I grew up in NYC in the 1950’s-60’s – and as amazing as it may seem compared to the last 20 yrs – NYC was wide-open when it came to the 4th of July. Most of the fireworks came from South Carolina, and you could get bricks of Camel firecrackers for $4.50; Ash Cans (M-80’s) for $6/GROSS. I went through so many packs – and tossed every label. I experimented with making fireworks (you could still buy the Chems needed in NYC until the late 60’s) My addiction to fireworks went into hibernation by 1970, but in 1989, I suddenly got the urge to shoot ‘real’ fireworks. And during the following 20 years, I ran large public displays, and pretty much ‘looked down’ on ‘toy’ fireworks (like fire crackers). But over the last couple years, I’ve become quite attracted to old firecrackers and the awesome labels found on them,; and lament my lack of foresight in what I could have now if only I had saved them from the thousands of packs I shot when I was a kid.

A couple other details on the evolution of crackers in the US: in 1967, the Gov’t crack down on anything that went boom led to the demise of heavily powdered crackers, with the new limit of 2 grains (about 130mg). Following the 4th of July in 1975, the limit was changed to 50mgs. And in the late 1990’s/early 2000’s, the use of clay type ‘plugs’ in firecrackers began. On the one hand, the use of clay type material may lead to a slightly louder cracker that still could not exceed 50mgs; but in many modern brands, this ‘filler’ enables manufacturers to use even less flash powder, reducing their noise level to what toy cap guns use to produce when I was a kid.

A fabulous article, I live in Australia where firecrackers were freely available into the very early 1980s, when successive state (Labor) governments outlawed their use in virtually all states of the country, we celebrated the Queens birthday and the fourth of July, many people saw the ban of their use as an attack on celebrating our English traditions and personal freedom in general. This current New Years Eve (2015) saw a huge amount of illegal private fireworks being sold on the black market imported largely from the huge amount of mainly Chinese immigrants that have flooded into Australia bringing their enthusiasm for celebrating their own traditions like Chinese New Year with them, which was exactly what the communist Australian Labor Party elements tried to stop back in the early 1980s!. Great to see in the United States that you can still legally celebrate you’re traditions!, it’s more than just firecrackers its you’re freedom at stake so if you can, keep fireworks legal in next America!.

Lots of errors and misleading statements.

i remember july 5 as dud day and i would wake up early and get on my bicycle and look for the unexploded packs and single firecrackers i would sometimes break them in half but not separated- lite the middle and stomp on it after lit and it would make a loud “report”. when i could find labels i would save them especially “MAT” labels that held 80 packs or more. 16 t0 20 in a pack, sometimes more. Brands like Black Cat, Red Leaf, Grenade, Phoenix, Peacock, Camel, Atomic, and more. i ended up with a large collection of the great artwork but threw them out in the 1990’s which i now regret. in rememember in the late 60’s i would buy a case of mats for 30 dollars (10 mats) and sell them for twice the money or more getting all my stuff for free after getting rid of half a case. i sold only to friends as to not get in trouble with the local cops! I would love to buy some of them old labels that i threw away..