Near a dusty stretch of train track on the outskirts of Barstow, California, the imposing Casa del Desierto—or House of the Desert—stands silent, its arched colonnade emptied of the railroad passengers, restaurant diners, and overnight guests who once visited its elegant hotel. The forlorn red-brick façade no longer greets crowds of visitors headed west to the California coast or east to the Colorado mountains, interrupting their journey for a respite at this cosmopolitan oasis. In fact, of around 100 Harvey House restaurants and hotels that were once scattered across this vast expanse of American desert, only a handful are still standing today.

“It was an adventure—not the same Holiday Inn over and over again.”

Fred Harvey was said to have “civilized the West” by bringing middle-class values to hardscrabble frontier towns, but his real accomplishments were more impressive: Harvey’s business model established the modern chain restaurant, created a major tourist market for Native American art, and gave opportunity to scores of young women escaping the confines of their Midwestern upbringings. In the late 19th century, Harvey Houses put many small towns on the map, providing sophisticated accommodations and magnificent public architecture that often became the locus of these communities, both culturally and economically. Through its promotion of the region’s landscape, architecture, and Native American cultures, the company also built a lasting fantasy of the American Southwest.

Like most Harvey Houses, the Casa del Desierto began losing business in the 1930s with the construction of Route 66—the black asphalt roadway that unfurled only a few thousand feet from Barstow’s train tracks, making Harvey’s rail-side accommodations obsolete. Though the 1911 building was saved from demolition in the 1980s (and now houses the town’s Chamber of Commerce and a couple of small museums), the closure of its Harvey House in the late 1950s marked the end of an era.

Top: A postcard of the Casa del Desierto from the 1910s. Above: The dining room at the Harvey House in Hutchinson, Kansas, circa 1920s.

“The Southwest became incredibly popular for various reasons, but partly because of Teddy Roosevelt’s idea of ‘roughing it,’” says Richard Melzer, author of Fred Harvey Houses of the Southwest. “The Harvey Houses gave people a way to explore the region without actually roughing it, so I think that made them particularly popular. Then you had the tremendous growth of California, and without that anchor at the end of the line, none of this would have been possible.”

As Lesley Poling-Kempes explained in her 1989 book on the Harvey empire, the company’s boom years marked the transformation of the Southwest “from a largely unknown desert and mountain wilderness to a popular region of small, thriving cities, a region that became a mecca for American and foreign tourism.” In addition to working-class Americans arriving in search of new opportunities, the railroads lured wealthier travelers with depictions of an authentic “untouched” territory, which presented native culture as a tourist attraction. “The Southwest became less the rugged frontier than the exotic backyard of America in the early decades of the twentieth century,” Poling-Kempes writes.

A 1903 postcard showing the interior of the “Indian Building,” or souvenir shop, at the Fray Marcos Hotel in Williams, Arizona.

This metamorphosis was dependent on transportation, specifically the Santa Fe Railway’s expansion from Kansas to California (the line’s name was eventually changed to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad.) Though its construction didn’t begin until 1868—the final spike of the first transcontinental railroad was driven in 1869—the Sante Fe had incorporated in 1859 with a planned route following the historic Santa Fe Trail. Used by Native Americans, Spanish explorers, French trappers, and other American tradesmen, this well-worn path began in Independence, Missouri, passed across Kansas and Colorado, and ended in Sante Fe, New Mexico.

Due to the mountainous terrain surrounding Santa Fe proper, the railroad’s engineers decided to build its main line through a town seven miles east instead, with a spur that extended up to Santa Fe. Eventually, the line reached south to Rincon, New Mexico, where it branched east to El Paso, Texas, and west to Deming, New Mexico. Directors of the Santa Fe line hoped it would later be linked to the Southern Pacific Railroad in Deming, completing the route all the way to Southern California.

Yet when the Southern Pacific began charging exorbitant freight rates to maintain its rail monopoly in the area, the Santa Fe partnered with a different company to build west across Northern Arizona near the Grand Canyon. This route was then linked with an existing railway in California, which the Santa Fe purchased in 1883 and joined with a north-south route it was constructing between San Diego and San Bernardino.

In the mid 1880s, the Santa Fe railroad purchased other lines connecting to the Gulf of Mexico at Galveston, Texas, and on to Chicago from Kansas City, making it the longest rail network in the world. Finally, the company acquired track into Los Angeles in 1887, completing a reliable new route from Chicago to the Pacific Ocean, the most important passenger line for Americans heading west.

A complete map of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad in 1891. Via Wikimedia. (Click to enlarge)

While California’s land of plenty was drawing large numbers of emigrants over the new rails, competition with other railroads also meant that fares were steadily decreasing. At the time, the Western United States was still chock-full of roughnecks seeking their fortunes, with small towns in Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona mostly populated by single men who came to farm, mine, ranch, or work on the railroad. Before the region became a tourist hotspot, the vast majority of visitors were also working-class men.

“Harvey Houses gave people a way to explore the region without actually roughing it.”

Temporary accommodations were sorely lacking, leaving folks who rode the rails to explore the region’s epic landscapes or make a fresh start for themselves with few creature comforts along the way. “There were virtually no clean hotels—their place was taken by shacks or public rooms with cots,” Poling-Kempes writes. “The food was usually served by a bartender or saloonkeeper. In the middle of nowhere, without adequate manpower, food supplies, or motivation, home-cooking meant making do.”

On top of the unsavory food options, the rail schedule allowed passengers only 20 minutes at each stop. Unscrupulous entrepreneurs used this to their advantage by charging for meals that weren’t served before the train had to reboard and leave for the next station. “People could bring their own food, of course, but it wasn’t convenient,” Melzer says.

In the 1870s, while working as a freight agent for a rail company based in St. Joseph, Missouri, an Englishman named Fred Harvey saw opportunity in this underserved customer base. Along with a partner, Harvey opened his first two restaurants in 1875 in tiny towns along a rival railroad running between Kansas City and Denver. Although the business partnership failed within the year, Harvey’s restaurants had been quite popular, so he pitched his current employer—the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad—on a series of restaurants built along its network of routes. Company executives rejected the idea but suggested Harvey try working with the bolder Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad.

The Santa Fe’s superintendent, Charles F. Morse, liked Harvey’s plan and knew firsthand the dearth of quality food along its burgeoning routes. Morse got the company’s president on board, and the Harvey restaurant experiment began in 1876. “It started out with just a handshake agreement that Harvey would manage these restaurants if the Santa Fe would build them,” Melzer says. The basic arrangement was that the Santa Fe would offer Harvey space in its Topeka depot for his first restaurant and would transport any supplies and restaurant staff free of charge. Meanwhile, Harvey would pay for those supplies, as well as all cooking equipment, and handle day-to-day management.

Diners in a Pullman car managed by Fred Harvey on the Santa Fe line between Chicago and Kansas City, circa 1888.

Topeka’s new lunchroom was an immediate hit with passengers, railroad employees, and locals, who filled the counter to enjoy Harvey’s fresh food, prompt service, and orderly environment. Harvey quit his job with the Burlington and began opening dining rooms at other stops throughout Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico, as the Santa Fe continued its expansion into Southern California. The trackside “eating-houses” were soon known as Harvey Houses, and to capitalize on their success, the Santa Fe adopted the advertising slogan “Meals by Fred Harvey.”

By the late 1880s, there was a Harvey House operating every hundred miles along the Santa Fe railroad, which usually meant a three to four-hour ride between each stop. “The Santa Fe would build them at division points where the train would refuel, refill its water supply, and get a new crew. That took about half an hour,” Melzer says, “which became the ideal time slot for passengers to get their meals. The Harvey Houses were such an efficient operation, especially as they improved over the years.”

Nestled in the mountains near Las Vegas, New Mexico, Fred Harvey’s Montezuma Resort was his largest and most luxurious hotel project, featuring a spa with several hot springs. Postcard circa 1880s.

Orders would be sent ahead from the train via telegraph so the staff would know how many people to expect and what meals they had to serve. “They could even predict what percentage of the people on each train would be served for breakfast, lunch, and dinner—and the largest crowd was always breakfast. When the train arrived, somebody would hit a big gong,” Melzer says. “That was like the starter pistol, so everyone was in place and knew what they had to do. Next, the servers would go by and get the drink orders, and depending on what the customer ordered, the staff used a cup code: If the customer ordered coffee, they’d put the cup up, or for hot tea, they’d put it upside down, and so on. The house manager would very calmly announce when there was only 10 minutes left, asking customers to please finish their meals and get on the train. Even the swivel chairs were meant to get customers in and out fast and efficiently.”

Menus were varied along each route so that diners had different choices at each stop. Using train cars refrigerated with ice, the Harvey Houses could serve fresh fish from the Great Lakes, fruit from California, beef from Texas, and oysters from the East Coast. Harvey House menus included items like Cold Vichyssoise, Poached Eggs à la Reine, Guacamole Monterey, Filet Mignon, Stuffed Zucchini Andalouse, Veal Scallopini, Cauliflower Polonaise, Curry of Lamb, Wild Canadian Goose, and Lemon Chiffon Cheese Cake.

A pamphlet given out by the Santa Fe Railroad featuring the Fred Harvey food. Via the Kansas Historical Society.

Other railroads tried to copy the format, but Harvey’s high standards were nearly impossible to match. Harvey made regular visits to each restaurant for unannounced inspections, and supposedly, if profits increased too much, Harvey became suspicious that the staff was cutting corners. Though the restaurants mostly operated at a loss, they gave the Santa Fe a competitive edge and increased ticket sales.

Melzer points out that Fred Harvey restaurants offered three major innovations for rail passengers: “The first was the great quality of the food, some of which the Fred Harvey Company produced on its own farms and ranches in the Southwest. Second, meals were inexpensive because the company could move everything on the Santa Fe Railroad, so it had no transportation costs. Then, of course, the restaurants had the tremendous service of the Harvey Girls, who were the face of the operation.”

In 1883, Harvey had decided to fire the rowdy male waiters at his restaurant in Raton, New Mexico, and hire respectable young women in their place. Customers responded so positively to the female staff that Harvey began replacing all of his company’s male servers, advertising for women employees in newspapers throughout the Midwestern and Eastern states.

Unlike much of the Eastern United States, in small Western outposts, it was acceptable for single young women to work and live away from their parents—though they were often stigmatized as being prostitutes or sexually promiscuous. “The Harvey Company called its servers ‘Harvey Girls’—not waitresses—because the term waitress had a bad connotation: It was linked to the saloon girls,” who were viewed as bawdy and indecent, Melzer says. “Fred Harvey didn’t want customers thinking there were saloon girls at his restaurants, and he certainly couldn’t recruit respectable women to work there if they thought they’d be working in a saloon-like atmosphere.” To ensure there’d be no confusion, the Harvey Girls were always attired in a conservative black-and-white uniform, just one of many strict job requirements.

Left, the Harvey House counter in Rincon, New Mexico, features the company’s distinctive swivel stools, circa 1920s. Via the Kansas Historical Society. Right, three Harvey Girls in uniform, circa 1900.

Harvey had no trouble finding suitable young women, despite the perception that the Wild West would scare them off. In fact, many women jumped at the opportunity for economic independence, adventure, and travel in an era when their prospects were greatly limited. “A lot of them came for the chance to see a different part of the country,” Melzer says. “After six months at a Harvey House, you could be transferred, so even if you started in a small place like Belen, New Mexico, you might eventually get to Santa Fe or to the Grand Canyon. Others came for the money, hoping to send it home to their families, save for their education, or maybe open a business themselves someday.”

However, many took jobs with the Fred Harvey Company for a more traditional reason: The high ratio of single men to single women meant they had great prospects for meeting potential husbands. Yet even with such a goal in mind, women who moved west were often required to step out of their traditional roles simply to survive.

As Poling-Kempes writes, “the society of the West gave the women freer rein in business ventures, more involvement in community life, and the opportunity for economic advancement. We know that many women did not openly or consciously challenge their roles, or overtly question their way of thinking about themselves, yet the popular literature of the period often claimed, true or not, that the West offered influence and power to women who ventured into it. There seemed to be a collision of signals and values: a chance for women to expand their roles in the new West, along with an equally strong expectation that they would maintain the status quo.”

When a new Harvey Girl accepted her job, she agreed to follow a list of employee regulations, including moving wherever she was needed and waiting to get married until the end of her contract. “The Harvey Girls had to live at the Harvey House or whatever facility the company offered them,” Melzer adds, “where they had a sort of ‘dorm mother’ or chaperone and a strict curfew. But they all had stories about how they’d break the curfew.” Even local women were required to live in company housing to ensure uniformity and prevent conflict.

Despite the often-patronizing rules, women working for Fred Harvey developed a kind of collegiate sisterhood, a community that maintained its bonds long after members had quit working as Harvey Girls. “I read the obituaries every day, and when a former Harvey Girl dies, they always mention it,” Melzer says. “It’s like being in the Green Berets—it was something they were really proud of because it was respected and admired.”

Instead of hiring Native American women as Harvey Girls, the company asked artists like Elle of Ganado, a famous weaver, to demonstrate and sell their wares in hotel lobbies and gift shops. Elle was even featured on a company postcard, circa 1906.

Working for Fred Harvey was a prestigious job that gave uneducated rural women a chance to raise their social and economic status—although, of course, this opportunity was restricted to white women. While Fred Harvey did hire some African Americans, Native Americans, and Mexican Americans, the company placed them in roles that would be invisible to customers, like janitorial work, housekeeping, or food preparation.

On the customer side, non-white diners were often forced to eat in an area separated from the main dining room and served by busboys rather than the famous Harvey Girls. “The company was pretty racist, but at that time, it was assumed employers would be,” Melzer says. “The Harvey Girls were almost all white women, though that changed during World War II.”

Although non-white employees were limited to jobs behind the scenes, the company was unique in its hiring of recent white immigrants for a variety of roles. This was strategic, since many of the company’s chefs came from the finest restaurants in Europe and spoke languages other than English, while at the same time, the popularity of railroad tourism meant many Harvey House guests also came from far across the globe. “They paid higher wages to staff who could speak multiple languages, especially at places like the Grand Canyon,” Melzer says. “They wanted to make foreign tourists feel more at home.”

Eventually, Harvey realized passengers also needed decent lodging for overnight stops, so in the 1880s, he began adding hotels to the business model, including rail-side accommodations and a few high-end resorts further from the main line. “You could go from one Harvey House to the next and know you’d always have outstanding service and quality rooms, as well as food,” Melzer says. “But you could also expect each one to be slightly different, so it was an adventure—not the same Holiday Inn over and over again.”

Some of the most successful hotels operated by the Harvey Company were the Castañeda and Montezuma hotels in Las Vegas, New Mexico; La Fonda in Santa Fe; the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque; the Casa del Desierto in Barstow, California; and La Posada in Winslow, Arizona. Fred Harvey had also been managing the Santa Fe dining cars since the 1890s, which he kept as clean and efficient as his stand-alone restaurants.

In small towns across the Southwest, a Fred Harvey establishment frequently became a community’s main hub. The spaces weren’t only prized by cosmopolitan tourists, but also locals who knew the entire staff and held special events there. “Most of these towns didn’t have other restaurants in those days,” Melzer says. “Civic organizations very often had banquets there and high-school seniors had events there, so it was a community center, too. Some local businessmen would sit at their own reserved stool every morning, and the Harvey Girls knew exactly what they would order. Then, of course, you had the railroad workers who got a discount, so they’d come by a lot, getting so friendly with the Harvey Girls that many ended up married to each other.”

The cover of a 1938 brochure advertising Mary Colter’s Bright Angel Lodge at the Grand Canyon. Via the University of Arizona.

When Fred Harvey died in 1901 from intestinal cancer, he was running 15 hotels, 47 restaurants, and 30 dining cars for the Santa Fe Railroad. Under the management of heirs, like his son Ford Harvey, the business continued to grow and flourish. In 1902, the Harvey Company hired Mary E.J. Colter to decorate the Alvarado Hotel’s new Indian Building, and afterward, her relationship with the company grew until Colter became its chief architect and interior designer, at a time when there were only a handful of certified female architects in the United States.

Colter was attuned to the Southwest’s regional aesthetic, incorporating the legacy of indigenous art and Spanish colonial buildings into her work for the Harvey Houses. “Mary Colter started with the Indian Building at the Alvarado Hotel,” Meltzer explains, “and altogether, she was involved in 22 different projects, especially places like El Navajo at Gallup and La Posada at Winslow, New Mexico.

“She was exacting, to say the least, but she was great at designing a building and its features in relation to the local landscape and culture—that was true of all the Harvey Houses,” he says. “These were not East Coast-style structures transplanted here. I remember a story about when they were installing tile flooring outside the rooms at La Posada in Winslow, Arizona. Colter wanted those tiles to be made of a material that would reduce the sound of people walking or moving luggage around. And when that didn’t happen, she told them to rip it up and do it over again.”

Perhaps Colter’s greatest accomplishments were her many projects at the Grand Canyon, which was then a relatively unknown jewel in the Northern Arizona desert. In 1903, the Harvey Company began developing the canyon’s first tourist hotel, El Tovar, designed as an imposing log-and-boulder structure by the Santa Fe Railroad’s chief architect, Charles Whittlesey. Colter’s contributions to the area included the interior design of El Tovar; concession buildings like the Hopi House, Hermit’s Rest, Lookout Studio, and Desert View Watchtower; the mid-priced Bright Angel Lodge complex; and the rustic Phantom Ranch located at the bottom of the canyon.

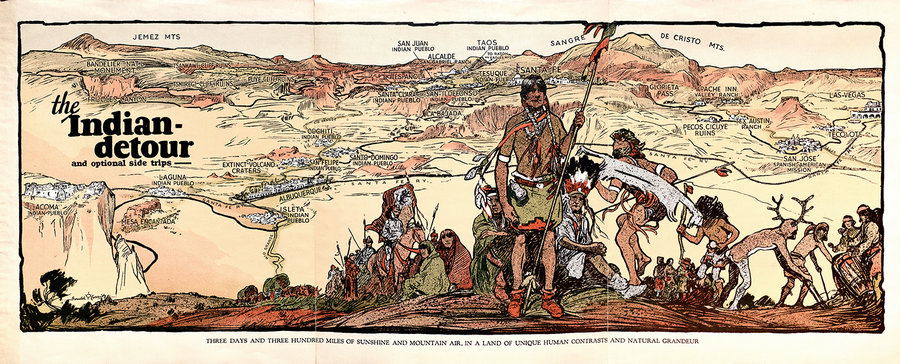

The same year Colter was hired, the Fred Harvey Indian Department was formed, leading the company’s acquisition of decorative objects, like rugs and pottery, and working with local Native American groups to showcase their skills in Harvey House gift shops and lobbies. “The Harvey Houses created a great new market for Indian arts and crafts,” Melzer says. “In places like Albuquerque, Native Americans weren’t hired as employees, but they could sell crafts to tourists, which enhanced the cultural atmosphere and the ‘exotic’ feeling of being at a Harvey House.” During the 1920s, the Harvey Company launched its Southwestern Indian Detours, with local guides leading one- to three-day sightseeing trips by automobile, which began and ended along the Santa Fe line.

“In the 1930s, along with the Great Depression and competition from other forms of transportation, the Harvey Company shot itself in the foot by improving the Santa Fe dining cars,” Melzer explains, “meaning more people weren’t getting off the train in order to eat.” Though the company continued to grow in other areas—including freestanding restaurants near highways, airline catering, and an expansion of its national park operations—faster train speeds, plus the rise of airplanes and automobiles, drew customers away from Harvey Houses, forcing several to close.

Although World War II provided a brief increase in train traffic, especially traveling military troops, the tide was turning toward cheaper highway motels and drive-in restaurants along major arteries like Route 66. “I always think that the Harvey Houses were just pointing the wrong direction,” Meltzer says, “because they were facing the train tracks rather than the road, with the exception of the Alvarado. The Alvarado was on Central Avenue in Albuquerque, which became part of Route 66, so it survived longer than most—until 1970—largely because it attracted business from both directions.”

A “Saturday Evening Post” ad from the late 1940s for Fred Harvey meals in Santa Fe dining cars. (Click to enlarge)

During the 1940s, as many Harvey Houses were struggling, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced a nostalgic film called “The Harvey Girls” based on a book of the same title. Starring Judy Garland and Angela Lansbury, the movie romanticized life in the Old West, and many Harvey employees felt it dismissed the demands of the job.

The business partnership between the Fred Harvey corporation and the Santa Fe railroad continued until 1968, when its remaining Harvey House properties and other new enterprises were acquired by the hospitality chain Amfac, Inc., now known as Xanterra. “Some of the Harvey Houses were used for other purposes, like museums or government buildings, but most were torn down,” Melzer says. A few of the company’s original hotels and restaurants, like those at the Grand Canyon and La Fonda in Santa Fe, are still open to visitors today. But the frontier spirit of the men and women who made the Harvey Houses unique faded long ago.

In 1957, architect Mary Colter’s greatest tribute to native culture—El Navajo in Gallup, New Mexico—was razed and replaced with a parking lot. That same year, the sumptuous La Posada in Winslow, Arizona, ceased operations and its interior fixtures were gutted. Shortly before her own death, Colter reflected on the demise of these once-great hotels: “Now I know there is such a thing as living too long,” she said.

The Casa del Desierto in Barstow, California, as it looks today. Via Chuckcars on flickr.

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes

Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes

Don't Call Them Bums: The Unsung History of America's Hard-Working Hoboes Coin-Op Cuisine: When the Future Tasted Like a Five-Cent Slice of Pie

Coin-Op Cuisine: When the Future Tasted Like a Five-Cent Slice of Pie Railroad ChinaRailroad china, like railroad silver, was a product of the boom in comfort …

Railroad ChinaRailroad china, like railroad silver, was a product of the boom in comfort … RailroadianaThe railroads built America: up through WW2 they were the dominant form of …

RailroadianaThe railroads built America: up through WW2 they were the dominant form of … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

It should be noted that the La Posada in Winslow, Arizona has had a slow recovery since 1997 and is mostly back in operation in very close to original look and feel, while the 5-star restaurant serves food you will never find elsewhere.

Oh, you can see the La Posada here: http://laposada.org/

I enjoyed this article. Of note, the Casañeda Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico was recently purchased by the same folks that bought and restored the La Posada in Winslow, Arizona. It can be visited along with Las Vegas’s other Harvey Hotel, the Montezuma Castle by contacting: tours@southwestdetours.com or calling 1 505-459-6987; Tour director Kathy Hendrickson is great.

The Montezuma currently houses one of the United World Colleges.

Except for some small details, one of the best most comprehensive description and history of the Fred Harvey system I have ever seen. Well Done

Daggett Harvey, the last Harvey to work for Fred Harvey

Thank you for a wonderful article. One of the earliest companies to provide real opportunities for women – both work and adventure. I’m amazed at the number of very small towns that had Fred Harvey establishments – Raton and Deming, NM to name a few. Being a native Texan, I knew that the railroad was significant as an employer and transporter of goods and people and connecting to the rest of the country. After a little research, I found that there were many Fred Harvey establishments in Texas and at least two have been restored – Slaton and Brownwood, TX.

Wonderful article. I shared it today on the Fred Harvey/Mary Colter Facebook page I manage. https://www.facebook.com/harveycolter/. I set it up with a bitly link and it shows as of this evening, 105 people clicked through to read it. It’s also appeared in over 2500 newsfeeds. It was also shared by 24 of the readers. Thank you for writing it. Our fans enjoyed it, liked it and shared it. High five!!

Great article. Loved the old photos selected.

—one of Fred Harvey’s direct descendants.

I believe that it was the Depression, which dried up business and recreational travel that reduced passenger traffic on the RR, rather than the (even by the standard of the time) creation of Rte 66. Other than that, a good article and one I’d like to include in my web page.

Thank you for such a wonderful article.

I have no connection with Mr Harvey, but thought it a very informative piece, of a place I would love to visit for its history.

Regards

Simon

This is a really interesting article. Railroad stories have played a huge part in the folklore and legend of the US, whether true or not, just as the railways made the US. I am currently researching and writing a book about the humble railway poster, one of series of nine and this one covering journeys around the United States. I found this fascinating article quite by chance. Well done Hunter!

I was looking for a ‘Super Chief’ post card on the internet. Glad to see you have one. I have another one and I will send a picture of, front and back. You can add to the one you have in this article. Its from the linen era (1930-45). This article made me look up the map that shows the Santa Fe railroad. I have 6 acres along I-40 / R66 and the Santa Fe is south of me, maybe 1/2 mile. Toot, toot!

My father, Gregg Stock ,was the director of SWAIA around 1987 in Santa Fe.

He came across this metal disc which I believe he was told that it had been in the dining car or lounge on the Santa Fe RR. Not sure what it dates to. I will try to enclose

a photograph. The diameter is approximately 33”.