The day after she returns from the 2014 San Diego Comic-Con International, comics icon Trina Robbins sits down with me outside at a café just around the corner from her home in San Francisco’s Castro District. As we talk and eat, trains from the Muni Metro railway come thundering by. Robbins’ partner, Steve Leialoha, a comic artist for Marvel and an inker for the DC/Vertigo series “Fables,” arrives fresh from Comic Con with his bags and joins us at the table for half an hour or so.

“When I got to San Francisco in 1970, I discovered that maybe it was the mecca of underground comix for the guys, but not for the girls.”

As both a comics creator and historian, Robbins is particularly interested in the unknown history of female cartoonists and the ways they were celebrated and thwarted throughout the last century. Late last year, Robbins published a Fantagraphics book called Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists, 1896-2013, and now, the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco is presenting an exhibition of Robbins’ personal collection based on the book.

The subject is particularly relevant right now, given that new comic-book-based movies are hitting the big screen every few months, yet not a single one has revolved around a female hero. Marvel has taken bold steps by making a Pakistani American teen the new Ms. Marvel, in a comic-book series written by a woman, and turning Thor into a woman in its upcoming revamp of the series. At the same time, the major publisher raised feminist ire with a sexualized variant cover of its new Spider-Woman series. If a woman had drawn Spider-Woman instead of a man, it’s unlikely she would have sacrificed the hero’s comfort and mobility in favor of an erotic pose.

Robbins knows something about the glass ceiling for women cartoonists because she first hit it herself in the early 1970s, when she tried to join the male-dominated “underground comix” movement based in San Francisco. After the men cartoonists shut her out, Robbins joined forces with other women cartoonists to create their own women’s-lib comic books. She went on to become a well-respected mainstream comic artist and writer, as well as a feminist comics critic who’s written myriad nonfiction books on the subject of great women cartoonists and the powerful female characters they created. Naturally, Robbins has spent some time hunting down the original cartoons from the women who paved the way for her career, and as luck would have it, she found the very first comic strip ever drawn by a woman, “The Old Subscriber Calls” by Rose O’Neill, practically in her backyard.

Top: Lily Renée’s cover for the November 1945 issue of Fiction House’s “Planet Comics,” featuring “Mysta of the Moon.” Above: Trina Robbins found a copy of the first published comic strip by a woman, Rose O’Neill’s “The Old Subscriber Calls” for “Truth” magazine in 1896, at a yard sale. Click image to enlarge. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“I found that comic in one of those houses, possibly the green one,” Robbins tells me, pointing across Church Street. “They were having a garage sale on the steps of the house, and they had two or three issues of ‘Truth’ magazine. I bought up all the copies of ‘Truth,’ and brought them home. What should I find but a comic by Rose O’Neill from 1896. That’s really kind of cosmic, isn’t it, that it was right around the corner from my house.”

Single-panel cartoons for adults, with text printed underneath the drawing, began to appear in publications in the mid-19th century, but to narrow her focus, Robbins starts Pretty in Ink with the early days of multiple-panel “comic strips.” The first, “Hogan’s Alley,” a strip by Richard F. Outcault about the slums of New York City, debuted in the pages of Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper “New York World” in 1895 and introduced the United States to the Yellow Kid, a bald orphan in oversized pajamas.

Just a year later, 20-year-old O’Neill sold the comic strip that Robbins found to “Truth.” The talented young artist had been living in the care of nuns at New York’s Sisters of St. Regis since she moved to New York City at age 18, and already, she was regularly selling illustrations to magazines and newspapers. For O’Neill, the comic strip was the next obvious step.

Grace Gebbie Wiederseim, later known as Grace Drayton, drew “The Turr’ble Tales of Kaptin Kiddo,” written by her sister, Margaret G. Hayes, in the 1900s. (Via MostlyPaperDolls.blogspot.com)

Soon after her strip appeared, O’Neill became the first female staff artist for the humor magazine “Puck,” where she created many single-panel cartoons. She also fell in love and married a gorgeous and lazy heir named Gray Latham. As a successful illustrator and cartoonist, O’Neill was doing quite well financially, when she could keep her spoiled husband away from her money—he would blow her paychecks on gambling and drinking. She divorced him in 1901, and a year later, married a “Puck” editor named Harry Leon Wilson. While they were both artistically productive during their marriage, Wilson’s moody temperament clashed with O’Neill’s bubbly personality, and he hated that she often talked to him in a baby voice.

“These women were so proud of who they were. The flapper movement was revolutionary. They got the vote. Think of it! They threw away their corsets!”

Another young female artist named Grace Gebbie also made her illustrating debut as a teen in the late 1890s. Then, in 1903, she set the tone for comic strips for the next 30 years, when she published the multi-panel cartoon “Naughty Toodles” in a William Randolph Hearst-owned newspaper, signed with her married name, G.G. Wiederseim. “Naughty Toodles” featured a round-faced, wide-eyed toddler, which became a trademark of her work. A year later, her advertising-executive husband asked to come up with characters for Campbell Soup, and she created with the iconic apple-checked Campbell Kids. From then on, the public just ate up comic strips featuring super cute roly-poly babies and children.

Grace Gebbie divorced Wiederseim in 1911 and married a broker named W. Heyward Drayton, and started signing her work “Grace Drayton,” the name most fans know her by now. She continued signing her work this way after she divorced Drayton in 1923. Throughout her career, Drayton produced an endless stream of adorable kids for comic strips, children’s books, and paper dolls—including Bobby Blake and Dolly Drake, Dotty Dimple, Kaptin Kiddo, and Dotty Dingle.

Rose O’Neill said her baby-like creatures she called the Kewpies, seen here in the April 1925 “Ladies Home Journal,” visited her in a dream. Click image to enlarge. (Via the State Historical Society of Missouri)

In 1909, O’Neill retreated to Bonniebroook, the mansion she built for her family in rural Missouri, to recover from the end of her second marriage. In response to the cuddly kids trend, her editor at “Ladies Home Journal,” where she regularly illustrated love stories, asked her to develop a Cupid-like cute-baby comic character. O’Neill became so obsessed with this idea that the characters visited her in her dreams, doing flips and tumbles on her bedcovers at Bonniebrook. She called her elfin, do-gooder, fat-baby-like creatures Kewpies, short for “Cupid,” and her drawings and verse introducing them in the “Journal” were a big hit. Within five years, Kewpies would be popular celluloid dolls, paper dolls, and postcards.

Drawing these big-eyed babies didn’t come from particularly girly or maternal impulses, Robbins explains. “Comics go through themes that are in style,” she says. “And in those days, cute kids were the trend. Men also drew these roly-poly toddlers. Richard Outcault drew Buster Brown, a cute kid.

Rose O’Neil and her sister Callista campaign for women’s suffrage. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“Everyone read newspapers and magazines,” she continues. “The women who drew cartoons were nationally famous superstars. People would cut out their strips and save them. You can find scrapbooks with these women’s cartoons pasted in them, sometimes colored in by a young girl. Nobody thought it was unusual for a woman to do comics because it wasn’t unusual for girls and women to read comics.”

After her second divorce, O’Neill, who had become independently wealthy from the Kewpies, swore off marriage and moved to the Greenwich Village, where she was the toast of the bohemian crowd. “She was beautiful, very pre-Raphaelite,” Robbins says. “She wore flowing velvet dresses that she created herself. In those days, to divorce and remarry was quite shocking, but she divorced twice. Grace Drayton did, too.”

O’Neill also campaigned for the suffragist movement, and for postcards, she even drew her Kewpies rallying to get women the right to vote. In fact, Robbins says most early women cartoonists were suffragists. “It simply goes together: These women were talented and intelligent,” she says. “And if you’re talented and intelligent, you’re going to be a bohemian and a suffragist.”

Another young feminist named Nell Brinkley arrived in Manhattan 1907, and once again, turned the tides in comic strips. While an illustrator named Charles Dana Gibson popularized a genre known as “pretty-girl art” with his aristocratic Gibson Girls in the late 1800s, Brinkley took it a step further. She started out at William Randolph Hearst’s “New York Journal-American,” producing lush illustrations that featured stunning curly-haired working-class women and ran with commentary below. Quickly, her Brinkley Girls were all the rage.

Nell Brinkley drew the art for the sheet music to “In a Canoe With You.” (Via University of Oregon Digital Library) The Ziegfeld Follies of 1908 reproduced the image in living tableau. (CarlaCushman.blogspot.com)

“The Gibson Girls are stationary; they sit on the beach in their cute, ancient swim costumes, smiling like Mona Lisa, and the men just all flock around them,” Robbins says. “Nell Brinkley’s women are extremely active. They surf, sled, and ski, with hair flying in the wind. A favorite subject for Gibson was showing these beautiful society girls being married off to ugly, old counts and dukes. Brinkley’s women never let people marry them off to nobility. They fell in love. It was a whole new generation. She didn’t create the New Woman, but she mirrored her.

Women who wanted Brinkley Girl curls could buy Nell Brinkley Bob Curlers.

“By 1908, she was already so popular that the Ziegfeld Follies added an act called The Brinkley Girls,” Robbins says. “The chorus girls would be dressed in white outlined by black to look like black-and-white drawings, and they would pose as famous Brinkley images in tableaux. She drew the cover to the sheet music for a song called ‘In a Canoe With You,’ and the drawing is a guy and beautiful girl rowing a canoe. The Ziegfeld Follies would copy it perfectly with the canoe, the pretty girl, and the guy. That means that everyone recognized the sheet music, and that tells you how popular she was. It’s the same way we recognize album covers; people parody ‘Abbey Road’ all the time.”

But women didn’t just want to watch Brinkley Girls onstage, they wanted to be Brinkley Girls. Companies like Bloomingdale’s department store took advantage of this trend and hired Brinkley to illustrate advertisements for their makeup, which was like the “Nell Brinkley seal of approval,” Robbins says. And Brinkley had her own branded hair products, too.

“If you wanted those wild curls that she gave her Brinkley girls, you could buy Nell Brinkley Bob Curlers or Nell Brinkley Hair Wavers.”

In 1918, during World War I, Hearst hired Brinkley to do color covers for its Sunday supplement “American Weekly,” which she turned into a comic serial called “Golden Eyes and Her Hero Bill,” inspired by the cliffhanger serial silent movies of the today. “It’s very feminist, about a woman called Golden Eyes,” Robbins says. “Her fiancé, Bill, goes off to the war and gives her his collie named Uncle Sam, who’s a really smart dog, like Lassie. Uncle Sam finds a German spy lurking in her backyard garden, which prompts her to follow her fiancé. She joins the Red Cross and goes to France along with the collie.

“In France, she crashes an ambulance in the forest, and she’s captured by this evil German officer with a little Kaiser mustache. Of course, he’s captivated by her beauty, so she plays along. She gets him drunk, and when he passes out, she steals his secrets and delivers them to her boyfriend’s troop. After a great battle, she finds her boyfriend wounded—of course, only in the leg—and drags him to safety. They all get medals, even the dog.”

Nell Brinkley’s World War I nurse Golden Eyes and her collie Uncle Sam in “Golden Eyes and Her Hero Bill” for “American Weekly.” (Via WikiCommons)

After the war, Brinkley pioneered the flapper cartoon, but unfortunately, she didn’t write the text, which turned her women into empty-headed party girls. “They were proto-comics because she didn’t have panels yet or speech balloons, just the words were underneath the pictures,” Robbins says. “It was simple verse. And it’s pretty silly, with big-eyed flappers saying, ‘boo boop bi doop.’”

But Nell Brinkley opened the door and started the flapper trend with her pretty girls, Robbins says. “Slightly younger artists like Ethel Hays and Virginia Huget drew all these cute flapper strips. The move away from old-fashioned kids in comics signified the ’20s. These women were so proud of who they were. The flapper movement was incredibly revolutionary. They got the vote. Think of it! They threw away their corsets! Women had always worn corsets. Suddenly, no corsets, just straight up-and-down dresses with knee-length skirts! Skirts had not been at the knee since ancient Sparta! Think of how amazingly revolutionary that was. They chopped off their hair! I don’t think that women had had short hair since the Empire period. And makeup! Up until then, only loose women wore lip rouge. Suddenly, perfectly nice girls, college girls, were wearing dark lipstick.”

This 1925 syndicated comic, “Flapper Fanny” by Ethel Hays, inspired the cover art of “Pretty in Ink.” (Via YesterYearsNews.wordpress.com)

Quickly, the funny pages were filled with stylish, wise-cracking young women. Among the most famous flapper cartoonists are Ethel Hays, who created “Ethel,” “Flapper Fanny,” and “Marianne,” and Gladys Parker, who took over “Flapper Fanny” and created the long-running “Mopsy” strip. But Robbins’ favorite is the less-well-known Virginia Huget, who created “Campus Capers” and “Babs in Society.” “She wrote them herself, so there’s more to the story than, say, the Nell Brinkley flapper comics,” Robbins says. “Babs works in a department store until some obscure rich uncle dies and leaves her a fortune, including his mansion. She’s this working-class girl who suddenly enters society, and she puts them in their place.”

After the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929, flappers were edged out by less-glamorous characters. In Pretty in Ink, Robbins characterizes Depression cartoons as “poor-but-happy American households; upbeat unflappable orphans; and plucky working girls out to earn a living rather than merely have a good time.” Perhaps the most archetypal Depression comic is Martha Orr’s “Apple Mary” about a big-hearted matriarch who sold apples on the street, which later was renamed “Mary Worth’s Family.”

“In the Depression, life was a little more serious because people were poor.” Robbins says. “You had strips about girls who had careers because they had to support their families, and these strips weren’t just created women. ‘Winnie Winkle the Breadwinner’ was by a man named Martin Branner.”

Martha Orr’s “Apple Mary,” a comic strip about a big-hearted grandmother who sold apples on the street, is the quintessential Depression cartoon. (Via Don Markstein’s Toonpedia)

Another poor but optimistic, independent, and adventurous woman debuted in 1937 with the strip “Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem,” created by Jackie Ormes, the first published African American female cartoonist. Appearing first in the black-owned “Pittsburgh Courier” newspaper and then syndicated to 14 other black newspapers around the country, “Dixie to Harlem” told the story of a young woman in the South who left the farm to become a singer and dancer at the Cotton Club in New York City. Torchy Brown’s comic went on hiatus starting in 1940, and then Ormes drew a couple of single-panel series, “Candy” about a black maid, and “Patty Jo & Ginger” about a little girl named Patty Jo, who was made into the first-ever vinyl black doll, manufactured in the Terri Lee mold.

The idea of compiling daily newspaper comic strips into booklet format started in 1897, when Outcault’s beloved character, the Yellow Kid, got his own book. But the first regular comic-book series didn’t appear until 1922, with publication of the omnibus “Comics Monthly,” which lasted a year. Comic books gained popularity in 1933, when Gulf gas stations started offering a comic book, “Comics Funnies Weekly,” for free, and that same year, publishers began producing comic books with original material, usually pulpy stories about crime, detectives, or adventure in faraway lands.

In Tarpe Mills’ 1940s comic strip “Miss Fury,” socialite Marla Drake has all sorts of noir-style adventures and sometimes even fights crime as a costumed crusader in a panther suit. (Via PrintMag.com)

Toward the end of the ’30s, the political climate in America had changed. With the rise of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party in Germany, war was on the horizon, and Americans were volunteering to fight the fascists. Who could defeat such a seemingly insurmountable evil? The first issue of the groundbreaking omnibus series “Action Comics,” published by Detective Comics, Inc., in June 1938, featured a new kind of hero, an alien with superhuman powers, wearing a caped costume typical of daredevils of the day. Superman fought bullies, oppressors, and dictators, in stories that alluded to Hitler and the Nazis, but never mentioned them by name.

This book launched the era that became known as the Golden Age of Comic Books. Suddenly, comics were all about action and adventure, whether it be new superheroes or plucky humans taking on baddies in the big city or foreign lands. In 1939, a woman named Tarpe Mills (born June Mills) drew a story called “Daredevil Barry Finn” for the “Amazing Mystery Funnies” book about a daredevil’s plan to foil Hitler and Mussolini. After that, she continued to create characters like the Purple Zombie, Devil’s Dust, and the Cat Man for comic books.

Dale Messick stepped into male territory when she created the action-adventure strip, “Brenda Starr, Reporter,” in 1940. Click image to enlarge. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

In 1940, the Chicago Tribune-New York News syndicate reluctantly accepted an action-adventure comic strip, by a woman about a woman, called “Brenda Starr, Reporter.” Even though Dale Messick, like Tarpe Mills, had changed her name from Dalia so it sounded more masculine, her status as a woman created obstacles for her. While the strip was a hit with readers and ran right up until 2011, Messick was subjected to an endless stream of vitriol from men in the field.

“Up until then, nobody had resented the other women cartoonists, but she was getting into men’s territory, the action strip,” Robbins says. “Before Dale Messick, woman cartoonists all stuck with domestic situations, pretty girls, cute kids, that kind of thing. She was intruding on men’s territory, and they resented it. As the result, men in the industry were not particularly complimentary about her art, and she felt very neglected by them. In 1971, the National Cartoonists Society gave prizefighter Jack Dempsey a ‘sports personality of the year’ award. And Dale Messick was quoted as saying, ‘I see where they’re honoring Jack Dempsey. They never honored me for anything, but they honor Jack Dempsey.’”

Dale Messick wears fabulous 1940s fashion in a publicity shot. Despite her success, she always felt left out of the boys club of male cartoonists. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

Messick’s sexy and stylish character, which took great inspiration from Nell Brinkley, eluded kidnappers, jumped from airplanes with a parachute, and got stranded on desert islands. “One of my favorites is where Brenda Starr joins this teenage gang,” Robbins says. “The gang leader is a blonde, and all the other members wear blonde wigs. She disguises herself with blonde hair and pretends to be a teenager so that she can join this gang of girl juvenile delinquents. Another time, she’s kidnapped by this albino Polynesian princess and winds up on this island where she discovers that her true love, the Mystery Man, Basil St. John, who is also being held prisoner by the Polynesian princess because she wants him to marry her. Messick came up with great stuff.”

In April 1941, Tarpe Mills introduced the world to the first major female action heroine, Miss Fury, in a syndicated comic strip. In it, a debutante named Marla Drake inherits a suit of panther skin that had once been an African witch doctor’s ceremonial robe, which she wears to a costume party. On the way to the event, she stops an escaped killer, and thus begins her days as a costumed crime fighter. Although, Drake rarely wears the panther suit, as Mills preferred to draw her in fabulous and revealing ’40s fashions in stories akin to film noir. And Miss Fury, too, takes off to confront Nazis in secret enclaves around the world. “She just starts out almost immediately fighting Nazis even though we weren’t at war with the Nazis yet,” Robbins says.

Gladys Parker took over Russell Keaton’s “Flyin’ Jenny” when he went into service in 1943. The comic strip told the story of an aviatrix who fought Nazis. Click image to enlarge. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

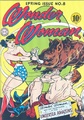

Miss Fury paved the way for dozens of comic-book heroines like her, mostly drawn and written by men, including Phantom Lady, Miss Masque, and Spider Widow. The most famous was Wonder Woman, conceived as a proto-feminist character by a psychologist named William Moulton Marston, who wanted to teach girls to stand up for themselves. Still, it would be 45 years before a woman would have any input into the stories and art for Wonder Woman, who debuted in December 1941, right around the time the attack on Pearl Harbor brought America into World War II.

At that time, many of the young men who were drawing and writing comic books enlisted to fight in the war. “As in every other industry, the guys are gone, and the women take their place,” Robbins says. “Women did things they’d never done before, including driving commercial trucks and buses, working in all the factories that are making planes, and drawing action comics for comic books. Almost invariably, they drew these beautiful, confident, fabulous action heroines who could handle anything. They rescue the guy and remain beautiful at the same time.

A quartet of women from around the globe come together to fight “Japanese barbarians” in Jill Elgin’s 1940s title “Girl Commandos.” (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“Barbara Hall drew a character called Blonde Bomber and a comic called ‘Girl Commandos,’ later drawn by Jill Elgin, which I like best of all,” she continues. “‘Girl Commandos’ are like this female United Nations commando group. Each one of them represents a different country that is being attacked by the Nazis, so you had a Norwegian one, you had a Chinese girl. The leader Pat Parker is a British woman. They all joined together to fight the Nazis.”

Fiction House, a publishing company started by Will Eisner and Jerry Igor, hired the most women in the ’40s. They published six themed titles—“Jumbo,” “Jungle,” “Fight,” “Wings,” “Rangers,” and “Planet”—with sensational stories starring powerful and gorgeous female characters.

“Fiction House is my favorite Golden Age comic publisher, if not just my favorite comic publisher, period,” Robbins says. “The two best women who worked for them were Fran Hopper and Lily Renée. Between them, they had Mysta of the Moon, whom I just love. She’s this beautiful woman who lives on the moon with her trusty robot, and her superpower is that she possesses all the knowledge of the universe. Fran and Lily both drew a character named Jane Martin who was an army nurse turned aviatrix, who fought the Nazis and flew planes.

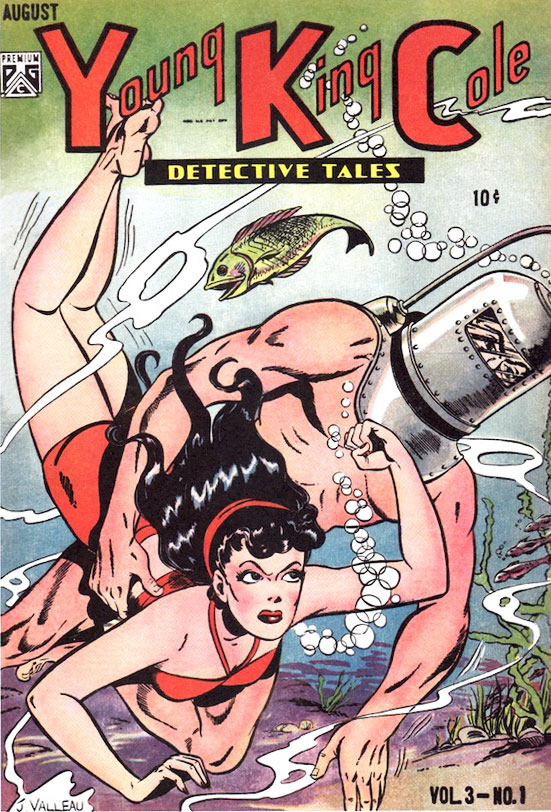

In 1946 and 1947, Janice Valleau drew Toni Gayle, a fashion model and detective, for “Young King Cole” comics. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“Lily Renée drew a series called ‘The Lost World,’” Robbins continues. “Men from the planet Volta attack Earth, leaving it in ruins. Among the survivors is Hunt Bowman, a handsome guy who’s an expert with the bow and arrow, and his companion, beautiful blond Lyssa, who wears fetching rags. They team up with other characters to fight the Volta men, who are thinly disguised, green-skinned Nazis. Lily was a refugee, a Jewish girl who escaped from the Nazis when they marched into Vienna in 1938. It’s wonderful that Lily was able to fight the Nazis on paper.”

After World War II, Gladys Parker showed her former flapper Mopsy happily giving up her war job. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

With the defeat of Hitler in 1945, the popularity of war heroes and superheroes in comic books waned, as titles about crime, horror, and love took off. When male cartoonists returned to their jobs, the women who were working by contract were simply not rehired. “All those great women that they drew also disappeared,” Robbins says. “For instance, Jane Martin, who was the flying nurse became a journalist and photographer after the war. No more flying.”

Some of the women artists did find work, drawing romance comics geared toward women. “After the war, men wanted women to go back to the kitchen,” she continues. “It’s not a coincidence that romance comics were in full bloom by the late ’40s. Their message is real propaganda. I don’t think that they were commanded by the government to have this message, but it was a belief everybody held at the time, which is: As a woman—no matter who you are, no matter what you do—you’re not going to find true happiness unless you meet the right man and get married, settle down, and raise babies.”

After the war, comics about teens—specifically “bobby soxers,” girls nicknamed after the socks they rolled down when swing dancing—exploded. Most of them took inspiration from Hilda Terry’s innocent comic strip, “Teena,” which first appeared on Pearl Harbor Day in 1941. In postwar America, adolescence was getting longer as more young people waited until after high school or college to get married, and teens became a particular fascination. Unlike the hard-working kids of the Depression, the teens of the 1950s Sunday pages lazed about the house. The girls chattered on the phone about boys, while the boys raided the fridge.

After the war, Linda Walter introduced Susie Q. Smith, a comic about a cute teenage girl who pined for boys. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“It was like the love comics,” Robbins says. “It was okay for women to draw cute, little teenage girls. They were a little ditsy and shallow, a lot like the flapper comics. But women in control and physically fighting bad guys was not permissible anymore. Ruth Atkinson, who had drawn for Fiction House, found work drawing ‘Millie the Model’ and ‘Patsy Walker’ comic books for Timely Comics.”

Fortunately, Dale Messick’s “Brenda Starr” kept having her reporterly adventures in the funny pages. And in 1950, Jackie Ormes revived her Harlem singer heroine with “Torchy Brown’s Heartbeats” and took her on many wild adventures through boat rides and jungles and hurricanes as she fell in and out of love. Unlike the melodramatic comics that appeared in white-owned newspapers, “Torchy” directly tackled issues around race and segregation, as well as environmentalism.

In the 1950s, black newspapers also printed Torchy Brown paper dolls by Jackie Ormes, the first published African American woman cartoonist. (Via Newmanology)

Even though women had been drawing and writing cartoons since the 1890s, when the National Cartoonist Society formed in 1946, women were excluded from joining, the stated reason being that the men felt they wouldn’t be able to swear in the presence of ladies. In 1949, “Teena” creator Hilda Terry sent the NCS a letter stating, “We must humbly request that you either alter your title to the National Men Cartoonists Society … or discontinue whatever rule or practice you have which bars otherwise qualified women cartoonists.” And she signed it from “The Committee for Women Cartoonists.”

Hilda Terry, the creator of “Teena,” put up a fight to be included in the National Cartoonists Society in 1949. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

The following year, Terry’s husband, a magazine cartoonist named Gregory D’Alessio, nominated both her and “New Yorker” cartoonist Barbara Shermund, and they were blackballed. But immediately after the vote, a loud debate broke out, and successful artists Al Capp, the creator of “Li’l Abner,” and Milton Caniff, the creator of “Steve Canyon,” argued forcefully for letting women join. The group held a re-vote, and this time, the women were approved. As soon as Terry got into the group, she nominated Gladys Parker and Tarpe Mills to the group.

But the comic-book industry was about to receive a major blow. In 1954, a psychiatrist by the name of Fredric Wertham published a book called “Seduction of the Innocent,” which claimed that comic books corrupted the minds of children with images of violence, sex, and drug use. Wertham asserted that Wonder Woman’s power and independence from men encourage girls to become lesbians. In response, comic-book publishers founded the Comics Code Authority that year to self-regulate their industry, and Wonder Woman was forced into more traditional feminine roles and eventually stripped of her powers. Having the Comics Code label on the cover meant wide, mainstream distribution, so artists that wanted to make money had to follow it.

“And it wasn’t just that book,” Robbins says. “Wertham wrote a lot of articles for magazines and gave talks. He was convinced that comics caused juvenile delinquency. I guess because the war was over, there had to be a new danger hiding under the bed. One of the dangers, of course, was communism, but another one was juvenile delinquency. In the prewar days, I don’t think anybody talked about juvenile delinquents. After the war, suddenly, everyone was worried about juvenile delinquents. People threw comics into bonfires. There were congressional hearings, which, in the end, caused the demise of many comics, and what comics were left were not doing that well, really.”

Ruth Atkinson, who had drawn bombers for Fiction House during World War II, created the teen series “Patsy Walker” in 1944. (Via MattFraction.com)

In the early ’50s, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman were the only superheroes that still had their own titles. But under the Comics Code, major publishers like DC, formerly known as Detective Comics, and Marvel looked to the noble and child-friendly superheroes to save the day in what became known as the Silver Age of Comics, starting in 1956. DC reworked the Flash, Green Lantern, and the Justice League of America, while Marvel introduced emotionally complex characters like Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, the Fantastic Four, and the X-Men, who all had real human flaws and struggles. Harvey Comics discontinued its horror series and put out comics for children like “Richie Rich,” “Casper the Friendly Ghost,” and “Little Dot.”

Ruth Atkinson also drew romance comics after the end of the war. (Via Lambiek Comiclopedia)

But these squeaky-clean mainstream comics seemed hopelessly outdated in the face of the hippie counterculture that emerged in the 1960s. Rejecting the values that they believed led the United States to engage in the Vietnam War, this youth culture embraced free love, psychedelic drugs, rock ’n’ roll music, and radical politics. In the mid- and late 1960s, artists like Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Vaughn Bodé, and Kim Deitch started drawing comics with explicit sexual imagery, references to drug trips, and socially conscious messages, and their books were sold in head shops. By the end of the ’60s, these artists were seen as leaders in the “underground comix movement.” “Comix” was spelled that way to emphasize that these were not your mainstream superhero comics following strictures of the Comics Code.

Even though they followed the Code, Marvel’s innovative new comics, which had more depth and human emotion than superheroes of the past, made college students see the format as a great way to express new ideas. The new superheroes were often social misfits as much as they were beloved guardian angels.

“In the ’60s, all of sudden, there were these new concepts in Marvel Comics, with the Fantastic Four, Thor, Dr. Strange, and Spider-Man,” Robbins says. “A lot of college kids and hippies—I was one of the hippies—read these things and thought they were really cool. I drew comics as a kid, but I had stopped. And as a young adult with artistic inclinations, I thought, ‘This is something I’d like to do.’ Inspired by Marvel, I tried to come up with a superhero comic about a doctor or a scientist who invents a psychedelic drug that enables him to fly and see through walls. But I’m not a superhero artist, so it just was not me and I didn’t finish it.”

Trina Robbins (top) in Donovan’s dressing room at The Trip, a club on the Sunset Strip in L.A., circa 1966. Everyone but Donovan (in the middle, sucking on a lily) is wearing clothes designed by Robbins. (Photo courtesy of Trina Robbins)

Right after that, underground newspapers started popping up, one of the first being the “L.A. Free Press” in Los Angeles, where Robbins lived and designed clothes for rock stars and their wives and girlfriends. But when she saw the “East Village Other” in 1965 coming out of the Lower East Side in New York City, she noticed it had comic strips, unlike the “Free Press.”

“During WWII, women drew action comics for comic books. Almost invariably, they drew these beautiful action heroines who could handle anything.”

“One of the strips, ‘Captain High,’ almost incorporated what I had wanted to do, a superhero whose powers had to do with pot and drugs,” Robbins says. “It wasn’t very well-drawn, but for us, it was brilliant because it was new and different. The ‘EVO’ had another strip called ‘Gentle’s Tripout’ by a woman named Nancy Kalish using the pseudonym Panzika, which was a full-page, totally psychedelic strip, very designy and pretty. It didn’t necessarily make a lot sense, but it was fascinating, and it inspired me. I was also inspired by Aubrey Beardsley at the time, so I started doing a very designy black-and-white, almost abstract kind of comic.”

Shortly after that, Robbins left Los Angeles for the Lower East Side, where she opened a clothing boutique called Broccoli to sell “really outrageous clothes.” There, she met up with the “East Village Other” staff, and they agreed to publish her comic called “Broccoli Strip,” featuring a character called “Suzy Slumgoddess,” inspired by the Fugs song, “Slum Goddess of the Lower East Side.” “The comic that I did for the ‘East Village Other’ was basically a free advertisement for my store, but it was very abstract and a lot of people just thought it was a comic.”

Trina Robbins poses in the window of her Lower East Side boutique, Broccoli, wearing a dress she made from an American flag. (Photo courtesy of Trina Robbins)

The underground comix scene was taking root in San Francisco, in part, because the Print Mint, a publisher in San Francisco and Berkeley, California, that started out making psychedelic rock posters, regularly published these comix, such as their anthology called “Yellow Dog,” which Robbins contributed to, and Robert Crumb’s “Zap Comix.”

“The underground comix movement grew as more and more people said, ‘Oh, yeah, we can do our own comics. They don’t have to be superhero comics. We can do comics about the life we relate to as hippies in the counterculture,’” Robbins says. “And it seemed like the exciting stuff was coming out of San Francisco. Underground cartoonists on the Lower East Side moved to San Francisco, and so did I. But then, when I got to San Francisco in 1970, that was when I discovered that maybe it was the mecca of underground comix for the guys, but not for the girls. To start with, there was only me and one other woman there, Willy Mendes, drawing comics, and we were left out of the scene.

“The guys would call each other up and say, ‘Hi, I’m going to put together a comic. Would you like to contribute?’” she continues. “But nobody ever called me. However, both Willy and I were good enough. Both of us eventually did our own comics with the Print Mint because the male cartoonists wouldn’t put us in their comics.”

Trina Robbins’ cover for “It Ain’t Me, Babe” the first women’s liberation comic anthology, first published by Last Gasp in 1970. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

Robbins, who had recently become a feminist, started to openly criticize the misogyny—particularly the images of rape and violence toward women—she saw in the men’s comix, particularly Crumb’s. “You can not imagine how threatened these guys were by women’s liberation,” she says of the male underground cartoonists. “It was ridiculous.”

“Women didn’t even want to go in those comic-book stores. They were terrible places, like porn stores.”

Shortly after she arrived in San Francisco, a friend showed her a copy of the first women’s liberation newspaper, “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” which came out of nearby Berkeley. She got in touch with the editors and met up with them at a Be-In, an event celebrating countercultural values. Soon, Robbins was doing covers, illustrations, and a back-page comic for the paper. “I suddenly had moral support. These women gave me the courage to put together an entire anthology comic book. And that was ‘It Ain’t Me Babe’ comics, which I co-produced with Willy Mendes. Published by Ron Turner at Last Gasp Comics, it was the first-ever all-woman comic anthology.”

The following year, Robbins published her own comic, “Girl Fight,” and Mendes put out a book called “Illuminations.” (“She was more on the mystic-mandala trip than I was,” Robbins says.) Robbins and Mendes also joined up with a third collaborator, Julie Wood, who went by the name Jewelie Goodvibes, and published a book called “All-Girl Thrills” with the Print Mint.

The contributors to “It Ain’t Me, Babe”: Far left, Meredith Kurtzman; standing from left, Carole, Peggy White, Michelle Brand, Willy Mendes; sitting from left, Trina Robbins and Lisa Lyons; far right, Nancy Kalish, a.k.a Panzika, a.k.a Hurricane Nancy. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“It Ain’t Me Babe” was a huge success for Turner and Last Gasp: The first print run of 20,000 sold out, and it was followed by two other runs of 10,000 copies each. This prompted Turner to seek artists and writers for an ongoing women’s liberation comic book, and so in 1972, a woman on his staff at Last Gasp, Pat Moodian, set up a gathering for any interested contributors.

“She called nine other women, including me, for a meeting at her house,” Robbins remembers. “We formed ‘Wimmen’s Comix,’ one of the very first continuing all-woman anthologies, and it lasted from ’72 to ’92, with roughly one issue per year. Right after our first edition came out, women all over the country were sending us contributions.”

Just two months before the first “Wimmen’s Comix” came out, another all-woman underground comix book called “Tits & Clits” hit the shelves. “In an amazing coincidence, on one side of California, in San Francisco and Berkeley, we were putting out ‘Wimmen’s Comix.’ Meanwhile, unbeknownst to us, in Southern California, Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevely were also reacting to the underground comix done by men. They were specifically reacting toward the way those guys treated sex, and they decided that they would do their own comic, ‘Tits & Clits,’ that dealt with sex from a female perspective. ‘Wimmen’s Comix,’ on the other hand, dealt with every subject.

The first issue of “Wimmen’s Comix” from 1972, with a cover by Pat Moodian. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

“At a ‘Wimmen’s Comix’ meeting, someone brought a copy and said. ‘Look what they’re doing in Southern California!’ We were totally blown away because we didn’t know they existed. They didn’t know we existed. And in 1973, there was a convention, one of the first alternative comic conventions in Berkeley, and we all met each other for the first time. We hit it off, of course.”

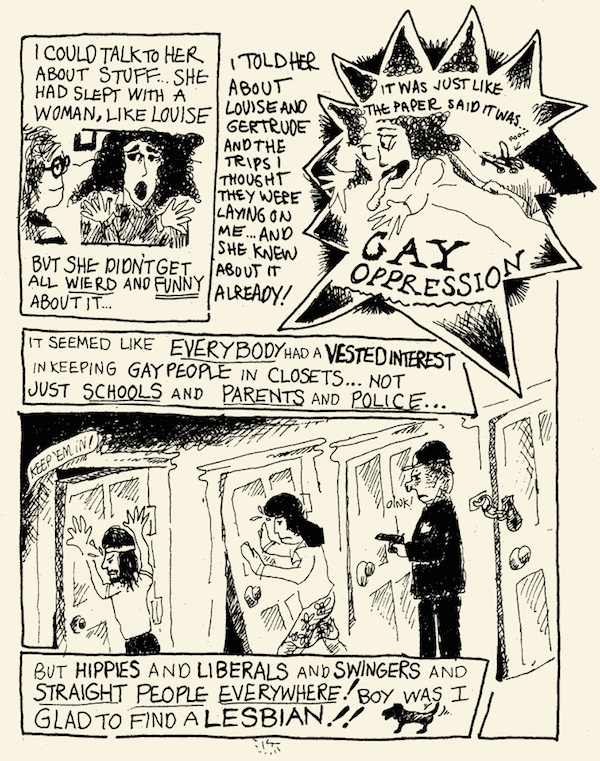

In that first issue of “Wimmen’s Comix,” Robbins contributed a story called “Sandy Comes Out,” which was based on her lesbian friend Sandy Crumb Pahls, and quickly faced criticism from Mary Wings, a lesbian and artist in the feminist counterculture community, for appropriating the homosexual experience.

“It was my ex-roommate Sandy’s story; I did it with her approval and her help,” Robbins says. “It felt like a good story for comix, and it didn’t occur to me at the time that it was the first cartoon about a lesbian, but it was. Mary Wings read it, and she thought, ‘This is outrageous! It’s a story about a lesbian obviously written by a heterosexual woman, and this should not be.’ So she printed her own comic, the first full comic book about life as a lesbian, ‘Come Out Comix,’ in 1973. We have since become good friends, and we laugh about it now.”

A page from Mary Wings’ “Come Out Comix.” (Via Underground ComixJoint)

However, as radical hippie culture faded in the late ’70s, distributing feminist and lesbian comix got harder and harder. “In the early ’70s, every major city and college town had a head shop, which sold rolling papers, psychedelic posters, bongs, and things like that,” Robbins says. “They also sold underground comix because it was the place to buy hippie stuff. But by the end of the ’70s, the counterculture was winding down, and a lot of the head shops closed.”

“The meeting was jammed, standing room only. It was spilling out into the street, because we couldn’t even fit all the women into the room.”

Around the same time, newsstands stopped giving rack space to comic books, and direct-sales sales stores, offering only comics, began to open. “The comic-book stores were usually run by some guy who was a comic-book fan himself, usually a superhero fan,” Robbins says. “All he really wanted to carry was superhero books. If he had any women’s books at all, he would under-order, maybe two or three copies. When he sold those, he would go, ‘Whew, got rid of those!’ and wouldn’t reorder. That was our major problem by the ’80s and the reason why ‘Wimmen’s Comix’ finally folded in ’92—distribution. We would get letters from women that said, ‘I love your comic, but I can’t ever find it.’

“Women didn’t even want to go in those comic-book stores,” she says. “They were terrible places, like porn stores. You would get to the threshold and look in, and there would be all these boys—ages 12 to 40, but the 40-year-olds were really still 12—just standing around, looking at comics. It was very unwelcoming for women. So the comic-book store owners could say, ‘Girls don’t read comics,’ because girls didn’t read the comics they stocked. But in the past, girls had read so many comics. Girls had gobbled up Nell Brinkley and saved her stuff and put it in scrapbooks. Girls loved ‘Brenda Starr’ and would copy it. As a kid, I loved ‘Patsy Walker,’ ‘Millie the Model,’ and ‘Katy Keene.’ Girls did read comics. But at that point, there were no comics in comic-book stores that girls wanted to read.”

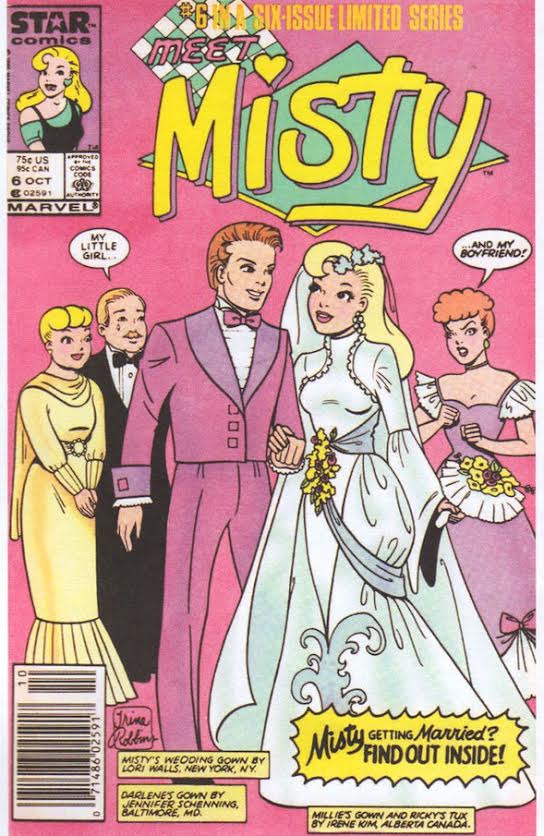

In the 1986, Robbins drew “Meet Misty” part of the industry’s attempt to revive comics for girls. (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

Robbins describes the ’80s as a drought for women artists and writers in comic books. At one point, only one woman, Ramona Fradon, was still working in creative for the major publishers DC and Marvel. Women cartoonists fared a little better on the funny pages, where Cathy Guisewite’s “Cathy” and Lynn Johnston’s “For Better or Worse” comic strips were showcased.

Alternative weekly newspapers, which had evolved out of the underground newspapers, became even more fertile ground for edgy women cartoonists. They carried strips like Lynda Barry’s “Ernie Pook’s Comeek” and Nicole Hollander’s “Sylvia.” New LGBTQ newspapers such as “WomaNews” and “San Francisco Bay Times” gave a platform for lesbian cartoons like Alison Bechdel’s “Dykes to Watch Out For” and Jennifer Camper’s “Rude Girls and Dangerous Women.” And in the early 1990s, two all-women bands, Bikini Kill and Bratmobile, paved the way for the riot grrrl third-wave feminist movement, which embraced the do-it-yourself punk ethos. Minicomics and fanzines were churned out on newly accessible computers, printers, and copying machines.

But things were just getting bleaker for women in the mainstream comics world. “By 1993, mainstream comics deteriorated to the point where women’s ideas were just about invisible,” Robbins says. “This was the period of what they call ‘bad-girl comics,’ which consisted of women characters with breasts bigger than their heads and really long legs wearing tiny outfits and super high-heeled shoes. The men drew these characters in what’s known as the ‘brokeback pose’ because you literally would have to break your back to stand like that. Any woman who picked them up would just be so insulted, they would just put them back down.”

Lynda Barry’s “Ernie Pook’s Comeek,” featuring awkward freckled girls, began appearing in alternative weekly newspapers in 1979. (From Lynda Barry’s TheNearsightedMonkey Tumblr, via “Pretty in Ink”)

That year, Robbins attended WonderCon in Oakland, California, and came face-to-face with real women being objectified to promote a comic. “There was this underground comic called ‘Cherry Poptart’ that really was soft-core porn,” Robbins says. “The guy who drew it had a very ‘Archie’-type style, but Cherry was always falling out of her clothes and the stories were explicitly sexual. It wasn’t totally obnoxious. The comics that I really objected to were ones in which women were horribly mistreated; this was more like just a fluffy, sexy thing. However, a convention is supposed to be for everyone, including women and children, not just horny men. At that WonderCon, the organizers actually had a Cherry Poptart look-alike contest, with all these girls, walking around in tiny, tight T-shirts with nothing under them—ugh! We women were so insulted that group of us went out to lunch and talked about how disgusted we were by the situation in comics.

“A few months later at the San Diego Comic Convention, writer and editor Heidi MacDonald Xeroxed an invitation for all women who worked in comics to meet at a certain cafe across the street from the convention,” she continues. “The meeting was jammed, standing room only. It was spilling out into the street, because we couldn’t even fit all the women into the room. That was the day we formed Friends of Lulu, an organization to encourage women to participate in comics as readers and creators in every way. I was one of the original Friends of Lulu, but Heidi was the mother of Friends of Lulu. Before the group dissolved in 2011, we had Lulu Cons. We gave out awards, Lulus, to women who would never get an award at a Comic-Con.”

Friends of Lulu put together this 2003 all-women comics anthology, “Broad Appeal.” (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

Thanks to this do-it-yourself spirit, self-published riot grrl zines and minicomics were flourishing in the 1990s. Usually done in a raw, rough-edged style, often with heavy, thick lines, these handmade comics showed characters with real human flaws, warts and all. Sold in independent record shops and bookstores around the country, some of these titles by women became quite famous, including Mary Fleener’s “Slutburger,” Megan Kelso’s “Girlhero,” Jessica Abel’s “Artbabe,” and Sarah Dyer’s “Action Girl.” That said, few of these women got paid well enough to quit their day jobs. But events like the Small Press Expo and Alternative Press Expo, which both started in 1994, gave them opportunity to connect, learn about, and buy one another’s work.

Early in that same decade, Art Spiegelman published Maus, a story about his father’s experience surviving the Holocaust, in the long-form comic format known as the graphic novel. His book wasn’t the first graphic novel, but in 1992, it became the first to receive a Pulitzer Prize, an accolade that made graphic novels the next publishing trend. Unlike comic books, graphic novels are thick and often contain one complete story. A thin comic book might be one piece of a larger story, or a compilation of shorter stories. While they are more like standard novels, graphic novels can be works of non-fiction, such as biography. According to Robbins, the rising popularity of graphic novels in the 1990s gave women a platform where they didn’t have to write or draw superheroes to tell a story in cartoons.

Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel “Persepolis,” first published in 2003.

“First of all, the graphic novel is closer to a book, so it’s more respected,” Robbins says. “It doesn’t have to be superheroes. And in fact, in most cases, it isn’t superheroes. It’s people telling real stories in every style under the sun, most of them really well-drawn, no matter what style they are using. In graphic novels, you get a wide variety of both men and women telling real, enjoyable stories that are not people just punching each other to bits.”

The big chain bookstores like Borders and Barnes & Noble that popped up in every town in the 1990s were more likely to carry graphic novels than the mall chains of the 1980s like B. Dalton and Waldenbooks. Before long, you started seeing women telling stories, both serious and lighthearted in this format. Over the next two decades, graphic novels let Iranian cartoonist Marjane Satrapi tell the story of her childhood in the Iranian revolution in Persepolis, Alison Bechdel depict her relationship with her closeted father in Fun Home, and Esther Pearl Watson’s compile her “Unlovable” strips, based on a teen’s 1980s diary she found in a gas-station bathroom. The graphic novel also became an accepted format for historical biographies about the likes of Emma Goldman and Isadora Duncan.

“The fact that they could be sold in bookstores and checked out in libraries created an accessible situation, where you didn’t have to go into the dreaded comic-book store that was all wall-to-wall boys and smelled like old gym socks,” Robbins says.

Megan Kelso drew and self-published her subversive minicomic “Girlhero” in the 1990s.

Through most of the ’80s and ’90s, mainstream American comic-book publishers insisted that preteen girls had no interest in comics. Meanwhile in Japan, publishers were having tremendous success with their “shoujo manga,” which translates to “girls’ comics.” When a manga called “Sailor Moon” was translated to English in 1997, it was a crossover hit. Soon, American publishers were releasing manga-style comics for girls.

“The women who drew cartoons were nationally famous superstars. You can find scrapbooks with women’s cartoons pasted in them, sometimes colored in by a young girl.”

On U.S. funny pages, women accounted for only 16 out of 240 syndicated newspaper comic-strip artists by the end of 1999. And in the new millennium, things weren’t looking much better at Marvel and DC. In Pretty in Ink, Robbins explains that a handful of women in this century have been successfully working for mainstream comic-book publishers, including Gail Simone, who created the all-woman superhero team “Birds of Prey,” but they are the exceptions.

In 2011, DC jettisoned all its old superheroes, 12 percent of which were written or drawn by women, and revived them as “The New 52,” with only 1 percent of the creators being women. Women who asked about this reduction at a San Diego Comic-Con panel preview were met with hostility from both the panel and the men in the audience. Marvel took a stab at hiring more women cartoonists in 2010, when it released a three-issue all-women anthology collection called “Girl Comics.” While the anthology was criticized for “ghettoizing” women, Robbins points out it was one of the rare opportunities female cartoonists had to work for a major publishing house.

Amanda Conner and Laura Martin drew the cover for Marvel’s 2010 all-women anthology “Girl Comics.” (Via “Pretty in Ink”)

However, the introduction of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s and the development of blogs in the 2000s opened more doors for women cartoonists. Many artists began self-publishing daily or weekly comics on their own web sites like Charlie “Spike” Trotman’s “Templar, Arizona” and Kate Beaton’s “Hark! A Vagrant.” The crowd-sourcing fundraiser site Kickstarter has helped other all-women anthologies come into being.

In some ways, mainstream comics publishers are finally starting to catch up. In 2014, Marvel introduced a new “Ms. Marvel”—Kamala Khan, a Pakistani-American teen girl from New Jersey—who was created by two women, editor Sana Amanat and writer G. Willow Wilson, and one man, artist Adrian Alphona. Even though the upcoming revamped “Thor,” series will be written and drawn by men, the “God of Thunder” character is now a goddess. As Marvel.com states, “’Thor’ will be the 8th title to feature a lead female protagonist and aims to speak directly to an audience that long was not the target for superhero comic books in America: women and girls.”

But Marvel also recently caused an uproar with a variant cover of the first issue of its new “Spider-Woman” series. Drawn by erotic artist Milo Manara, the character is posed with her large buttocks up in the air, in a costume so impossibly tight, it could only be body paint. At io9, Rob Bricken writes, “That’s a big no-no for an industry still trying to remember that women exist and may perhaps read comics and also don’t want to feel completely gross when they do so. … Perhaps asking an erotic artist to draw one of your most popular superheroines for a mass-market cover wasn’t quite a good idea.”

Golden Era comics artist Lily Renée, left, and Trina Robbins sign “Pretty In Pink” at the 2014 San Diego Comic-Con. (Via The Cartoon Art Museum Tumblr)

Still, comics fans appreciate the work of old-school female cartoonists. Robbins had a special treat at this year’s San Diego Comic-Con, when she got an email from the son of Lily Renée, who said the venerated Golden Age comic artist was visiting him in San Diego and wanted to attend the convention. Renée, who is in her 90s, joined Robbins, who wrote Renée’s biography for a graphic novel, at the Fantagraphics booth for signing. “People who know her were just thrilled,” Robbins says. “There aren’t a whole lot of the great Golden Age cartoonists left.”

Robbins says that with all the new developments, things are looking better for women cartoonists than they have in 100 years. “Superhero comics are not going to go away,” she says. “There’s always going to be a constantly revolving reader group of 12-year-old boys. But now there’s something else, made by people who want to go beyond 12-year-old boys. There’s something for girls, something for women, something for men who are interested in topics besides guys punching each other out. Really, at last, what’s happened is we’re back to comics for everyone, which is how it started, isn’t it? We’ve come full circle.”

In the new “Ms. Marvel” series—created by two women, editor Sana Amanat and writer G. Willow Wilson, and one man, artist Adrian Alphona—the heroine is Kamala Khan, a Pakistani American teenager living in New Jersey. (Via Marvel.wikia.com)

(Learn more about the history of female cartoonists in “Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists, 1896-2013.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Fightin’ Femmes: Unmasking Comic Book Superheroines

Fightin’ Femmes: Unmasking Comic Book Superheroines

Pin-Up Queens: Three Female Artists Who Shaped the American Dream Girl

Pin-Up Queens: Three Female Artists Who Shaped the American Dream Girl Fightin’ Femmes: Unmasking Comic Book Superheroines

Fightin’ Femmes: Unmasking Comic Book Superheroines Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood

Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood Underground and Alternative ComicsIf 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos o…

Underground and Alternative ComicsIf 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos o… Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat…

Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

As I recall from the times, and from publishing a number of SF comic artists, one of the reasons, although not the only one, for Robbins being shut out was that she simply wasn’t that good in scripts or in panels or in actual drawing. You have to remember that the group she was trying to be “accepted” by included Crumb, S Clay Wilson, Spain, etc. That was a tough crowd. Not that they didn’t have deep seated problems with women, but they also had huge talents against which Robbins was quite obviously a fourth stringer. To default into themes that were popular is to admit that you need PC to support you. Sort of like teaching “women’s studies” because you can’t teach studies.

Thank you for an eye-opening history lesson. It brought to mind Shary Flenniken, one of my all-time favorite cartoonist-storytellers of the 1970s, whose brilliant work—in particular “Trots & Bonnie”–now seems largely (and unfortunately) forgotten.

“But by the end of the ’70s, the counterculture was winding down …Robbins describes the ’80s as a drought for women artists and writers in comic books. At one point, only one woman, Ramona Fradon, was still working…”

Readers of this article should google “Elfquest” and “Wendy Pini” for a slice of comics history–and an incredibly successful female cartoonist–that always seems to be left out of Robbins’ histories.

Although there are some errors (e.g., Gail Simone wrote an acclaimed run of BIRDS OF PREY, but she wasn’t the creator of the concept), a very nice overview of women in comics. Kudos to Ms. Robbins for her efforts to ensure these women get the recognition they deserve.

The fun thing about the drawn book world today is that we have so much to choose from. It only scratches the surface of women in the art form. It’s not complete, of course, without Roberta Gregory – hard at work since the ’70’s – Carl Speed McNeil, with her fabulous “Finder” series, or even myself, who helped open up mainstream to gay characters and insightful historical comics with “The Desert Peach.” And that, of course, just scratches the surface. Get to digging – there’s a whole new world of women authors (art/writing/ownership) out there, and it’s not just in binders.

Trina discusses both “Wendy Pini” and “Elfquest” in “Pretty in Ink,” so be sure to check out the book if you want to see what she writes about the ’80s.

Er . . . Wonder Woman wasn’t “stripped of her powers” until 1968, almost two decades after the Comics Code was introduced. Wertham had nothing to do with it.

Details like this kind of undermine the whole article. Hey, thanks for noticing that detail! We fixed it in the article. Best, -Editors

No mention of Colleen Doran? Wow.

When you read the responses and how many women were left out of the article. One can only assume the writer either lacked the knowledge or purposely did so for the victimization entitlement credit.

The later being very much coveted these past few years.

P.S. if a man would have written this article, there would be many follow up articles stating that this man is very daft to the accomplishments of women in the field and the white male should have his female critique license taken away.

Oh the Irony.

No mention of Colleen Doran, and no mention of Marie Severin, either. Jo Duffy, Louise Simonson, Anne Nocenti, June Brigman, Jan Duursema, Cindy Martin, etc, all of whom were working in mainstream comics at a time when all Trina was working on was the very short-lived “Meet Misty”. That was in the 1980’s, when this article claims no women were working in mainstream comics. Horse hockey. There were dozens.

Trina’s histories of comics are, unfortunately, almost uniformly self-serving.

Hey folks,

Thanks for bringing the brilliant artists who were left out of the story into the dialogue.

Trina Robbins writes about hundreds of women cartoonists in “Pretty in Ink,” but unfortunately, we didn’t get the opportunity to go over every single one in our conversation. The book is a much more complete history than this article.

To Gerard Organ: Actually, Spain once TOLD me why the guys didn’t want to include me in their comix. He said that they WANTED to be violent and gruesome and sexist, and he referenced Ramona Fradon whom I quoted in one of my histories as saying that there was a certain sweetness in women’s comics that was not there in the comics by men. Spain said the reason the guys didn’t want me was because that sweetness was in my work. That made me happy, not just because he said my work was too sweet for the guys, but because it meant he had read my book.

Great article–but boy oh boy, that Art Adams closing image: didn’t think anyone would draw a large-breasted Kamala Khan in a brokeback pose and skin-tight uniform … but Adams did.

The noodnik, above, who rejects Trina’s work wholesale, is clearly just another monocular male. I have been collecting Trina’s work since pretty much her beginnings, and have always loved it. As she says in a comment, also above, it is full of sweetness, amongst other things — such as an astringent wryness, a nearly slapstick sense of humour, and a broad love of life and humanity, including male persons. The very worst thing about male-centered comics is the unrelieved grimness, and, of course, the endless resort to, and fascination with, massive violence. (Obviously, there are some exceptions.) I was extremely dismayed when Trina announced that she was stopping drawing. Her artwork had steadily progressed over the years, to the point that it was tight, compact, and highly decorative. And very pretty. Her story-telling was smooth and compelling. But “the boys” in the comics biz were still unable to understand her talents. Luckily, she had decided to concentrate on writing, and her career has soared in the last fifteen or so years. I love Trina, and I love her work.

Great article, great visuals. Good to see someone has brought together an informative, necessary and historical look as the past five decades and the push for inclusion within this popular culture and art connection. Glad the other half of the population has been aboard..although it was a hard and difficult train ride! Bravo!

” Drawn by erotic artist Milo Manara, the character is posed with her large buttocks up in the air, in a costume so impossibly tight, it could only be body paint.”

Yes, that is how spiderman has always been drawn.

” At io9, Rob Bricken writes, “That’s a big no-no for an industry still trying to remember that women exist ”

I don’t think they have any problem remembering.

“and may perhaps read comics and also don’t want to feel completely gross when they do so”

It’s a variant cover. You can’t buy it unless you seek it out. And who says women don’t like other women’s butts? Or should we chastise Nicki Minaj for being a slut?

“… Perhaps asking an erotic artist to draw one of your most popular superheroines for a mass-market cover wasn’t quite a good idea.””

Or perhaps it was a really good idea; it seems to have done well in terms of sales. The fact it offended a few prudish social justice warriors who never buy comics, but feel entitled to dictate to others what they should allowed to see, isn’t any great dilemma. You cannot appease such people. There will be no peace in our time.

And as for Thor, what Marvel has done is tell long time readers that they are no longer welcome, that they are to eb sacrificed for a new demographic… which reads manga, not superhero comics, which likes tales of magic girls and japanese culture, not the Norse gods.

It’s idiotic, and i predict a reboot in a year, maybe two at best, and then female Thor will be thrown out the window, never to return.

Thank you for this article–I’m looking forward to the book!

Don’t forget about Shawn Kerri. She was a great artist whose work I loved back in the 80s. I had no idea she was a woman until about seven years ago.

She did the poster and cover art for the Germs and the Circle Jerks and worked for Cracked and CARtoons. She was screwed by the Circle Jerks for her iconic Skankin’ Kid art.

hi, i am trying to find out if any modern comics groups for women, or run by women, because I have a unique friend who has a major blog(500-lb. peep) who is disabled with cushings’ disease; she does art,painting, &* is working on a comic book of her life,which reads like a novel.(her family was like a “Godfather-story-family,) and she draws and writes what its like to be 500 lbs. due to cushings’ disease, & be poor,& handle a mysterious, horrible family she escaped from. She is an activist for women, & espec. women who are BIG,& can’t help it.She is incredibly smart.And she has her own style of cartooning; CAN anyone tell me if there’s a company, or group, willing to get her in comix? it’s not the money. ARE THERE any women’s comic book groups or people left, to help? WHOM do i go to, phone, write, email, about getting her published? I don’t know if there’s any women in comics left from long ago, who still help beginners. Please advise. THANKS!!! :) (PLEASE READ HER BLOG, “500-LB. PEEP”) to see how well she edits, writes, researches; (her husband is a free lance editor) But she would be a GREAT ADDITION TO COMICS BY WOMEN. (money is a tight factor here, doubt she could self-publish) and you were just saying, womens’ themes have barely scratched the surface of comix. This person could really scratch it to death!! great personality. )

I can only suppose that Trina, being the great public voice of feminism that she is, somehow forgot to mention Aline Kominsky Crumb and Diane Noomin (myself)and the comic book Twisted Sisters, 1976, that we did back in the seventies.

thank you for this article!