Types

Makers

Action Figures

Building Toys

Characters

Space Toys

Toy Soldiers

Transport Toys

Other Toys

AD

X

Erector Sets

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

Alfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was a toy-industry titan, who was as shrewdly self-mythologizing as he was innovative. The first construction toy set was patented in England by Frank Hornby in 1901. These...

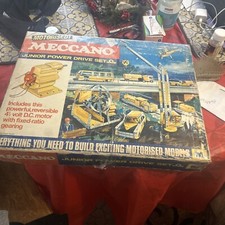

Alfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was a toy-industry titan, who was as shrewdly self-mythologizing as he was innovative. The first construction toy set was patented in England by Frank Hornby in 1901. These toys, named Meccano in 1907, consisted of half-inch-wide metal strips with holes at half-inch intervals. The strips could be connected with metal rods and wheels to build bridges, buildings, and vehicles of all sorts.

Meanwhile, in the early 1900s, A.C. Gilbert, the son of a successful businessman and a medical student at Yale University, was making a name as an athlete and a professional magician on the local vaudeville scene. In fact, at the 1908 London Olympics, Gilbert tied American Edward Cook for the Gold Medal in pole-vaulting.

Instead of going into the medical field, Gilbert stayed in New Haven, Connecticut, and in 1909, he joined up with his friend, John Petrie, to found Mysto Manufacturing to produce Mysto Magic Kits and provide supplies like interlocking rings, trick cards, and magic wands to magicians. Gilbert's company also offered kits to boys to teach them his personal values— discipline, poise, and mastery of a field.

Gilbert began to tinker with a construction-toy prototype he called Mysto Erector Structural Steel Builder, which he debuted at the 1911 New York City Toy Fair. In 1913, Gilbert began selling these Erector sets along with the Mysto kits. By 1916, Gilbert had ended his partnership with Petrie and re-named his business The A.C. Gilbert Company.

Gilbert claims he saw workers carrying the steel beams for an electrical power grid while traveling on a New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad train, and that inspired him to create the Erector set. But the truth is that Gilbert had probably seen or heard of Meccano.

However, Gilbert improved on Hornby’s concept by including gears, pinions, and electrical motors in his Erector sets to make them more versatile. Unlike Meccano’s steel strips, Erector set’s steel parts were bent at a 90-degree angle so that four of them put together could form a hollow support beam. The war in Europe disrupted the flow of high-end toys from Germany and England, which gave Gilbert an opportunity to establish his own "learning toy" brand.

In 1922, Gilbert expanded his "learning toy" line to include Gilbert-brand chemistry sets that let boy scientists play with dangerous chemicals such as potassium nitrate, nitric acid, sulfuric acid, sodium ferrocyanide and calcium hypochlorite. By the end of the decade, Gilbert took over the American branch of Meccano construction toys, which by then was popular all over the world. In 1934, he started offering microscopes for children.

Erector sets arrived in an era that celebrated industry and engineering. Modern buildings and power lines were being erected across the United States as speeding trains and automobiles connected cities and towns more than ever before. For rural families who did not yet have access to electricity, a boy's Erector set may have been the first motor in the home. Naturally, American parents hoped their boys—but not their girls—would develop skills in engineering and science that would take them far in this brave new world.

Gilbert, who idolized the masculine adventures of President Teddy Roosevelt, was the perfect figure to help parents channel these hopes about the future. He believed—or at least he convinced parents—that his toys, like Erector sets, would give their boys mastery, confidence, and patience. In the mid-1920s, the top-end Erector sets sold for $25, which could be a week's wage for a parent, but Gilbert persuaded parents that these "instruments of learning" were essential for success in a time when parents were reluctant to spoil their children with too much amusement.

Erector sets were time-consuming and difficult to build, with small parts that required dexterity and came with very little in the way of written instruction. For example, an Erector Ferris Wheel usually took 18 hours to complete, and therefore, the assumption was the boy would spend more time putting it together and taking it apart than playing with it or showing it off.

Gilbert advertised Erector sets in major national magazines like "Good Housekeeping," "Saturday Evening Post," "Popular Mechanics," and "American Boy." In these ads, he often addressed the boys directly, sharing his incredible life story and asking boys to write him with their ideas for Erector-set models. Gilbert was one of the early adopters for radio as an advertising vehicle, and he also began to sell radios in the 1920s.

Sensing the United States would soon be drawn into World War II, Gilbert opened a science museum and toy store for children in New York City called the Gilbert Hall of Science on September 17, 1941. That way, mothers and their little boys on the home front would be talking about his toy lines—which by then included Erector sets, Gilbert chemistry and science kits, and the American Flyer model trains he acquired in 1938—while Gilbert's factories were conscribed to make parts for the war effort. Gilbert, however, insisted that teaching children, and specifically boys, the principles of science and engineering was his No. 1 priority, and he opened other Halls of Science in cities around the United States.

By 1954, Gilbert was the most famous toymaker in the United States, but the peak wouldn't last long. That decade, his company offered an expensive science kit called the Atomic Energy Set with a working cloud chamber, Geiger counter, and radioactive samples—which was a big failure on the market. As more families purchased televisions and more factories put out cheap toys, interest waned in big-project educational toys like Erector sets and American Flyer model railroads.

A.C. Gilbert died in 1961, leaving it to his son, Alfred Jr. The Erector set name was first sold to Gabriel Toys in the '60s, and later to Ideal Toys.

Continue readingAlfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was a toy-industry titan, who was as shrewdly self-mythologizing as he was innovative. The first construction toy set was patented in England by Frank Hornby in 1901. These toys, named Meccano in 1907, consisted of half-inch-wide metal strips with holes at half-inch intervals. The strips could be connected with metal rods and wheels to build bridges, buildings, and vehicles of all sorts.

Meanwhile, in the early 1900s, A.C. Gilbert, the son of a successful businessman and a medical student at Yale University, was making a name as an athlete and a professional magician on the local vaudeville scene. In fact, at the 1908 London Olympics, Gilbert tied American Edward Cook for the Gold Medal in pole-vaulting.

Instead of going into the medical field, Gilbert stayed in New Haven, Connecticut, and in 1909, he joined up with his friend, John Petrie, to found Mysto Manufacturing to produce Mysto Magic Kits and provide supplies like interlocking rings, trick cards, and magic wands to magicians. Gilbert's company also offered kits to boys to teach them his personal values— discipline, poise, and mastery of a field.

Gilbert began to tinker with a construction-toy prototype he called Mysto Erector Structural Steel Builder, which he debuted at the 1911 New York City Toy Fair. In 1913, Gilbert began selling these Erector sets along with the Mysto kits. By 1916, Gilbert had ended his partnership with Petrie and re-named his business The A.C. Gilbert Company.

Gilbert claims he saw workers carrying the steel beams for an electrical power grid while traveling on a New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad train, and that inspired him to create the Erector set. But the truth is that Gilbert had probably seen or heard of Meccano.

However, Gilbert improved on Hornby’s concept by including gears, pinions, and electrical motors in his Erector sets to make them more versatile. Unlike Meccano’s steel...

Alfred Carlton "A.C." Gilbert, the entrepreneur behind the Erector set, was a toy-industry titan, who was as shrewdly self-mythologizing as he was innovative. The first construction toy set was patented in England by Frank Hornby in 1901. These toys, named Meccano in 1907, consisted of half-inch-wide metal strips with holes at half-inch intervals. The strips could be connected with metal rods and wheels to build bridges, buildings, and vehicles of all sorts.

Meanwhile, in the early 1900s, A.C. Gilbert, the son of a successful businessman and a medical student at Yale University, was making a name as an athlete and a professional magician on the local vaudeville scene. In fact, at the 1908 London Olympics, Gilbert tied American Edward Cook for the Gold Medal in pole-vaulting.

Instead of going into the medical field, Gilbert stayed in New Haven, Connecticut, and in 1909, he joined up with his friend, John Petrie, to found Mysto Manufacturing to produce Mysto Magic Kits and provide supplies like interlocking rings, trick cards, and magic wands to magicians. Gilbert's company also offered kits to boys to teach them his personal values— discipline, poise, and mastery of a field.

Gilbert began to tinker with a construction-toy prototype he called Mysto Erector Structural Steel Builder, which he debuted at the 1911 New York City Toy Fair. In 1913, Gilbert began selling these Erector sets along with the Mysto kits. By 1916, Gilbert had ended his partnership with Petrie and re-named his business The A.C. Gilbert Company.

Gilbert claims he saw workers carrying the steel beams for an electrical power grid while traveling on a New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad train, and that inspired him to create the Erector set. But the truth is that Gilbert had probably seen or heard of Meccano.

However, Gilbert improved on Hornby’s concept by including gears, pinions, and electrical motors in his Erector sets to make them more versatile. Unlike Meccano’s steel strips, Erector set’s steel parts were bent at a 90-degree angle so that four of them put together could form a hollow support beam. The war in Europe disrupted the flow of high-end toys from Germany and England, which gave Gilbert an opportunity to establish his own "learning toy" brand.

In 1922, Gilbert expanded his "learning toy" line to include Gilbert-brand chemistry sets that let boy scientists play with dangerous chemicals such as potassium nitrate, nitric acid, sulfuric acid, sodium ferrocyanide and calcium hypochlorite. By the end of the decade, Gilbert took over the American branch of Meccano construction toys, which by then was popular all over the world. In 1934, he started offering microscopes for children.

Erector sets arrived in an era that celebrated industry and engineering. Modern buildings and power lines were being erected across the United States as speeding trains and automobiles connected cities and towns more than ever before. For rural families who did not yet have access to electricity, a boy's Erector set may have been the first motor in the home. Naturally, American parents hoped their boys—but not their girls—would develop skills in engineering and science that would take them far in this brave new world.

Gilbert, who idolized the masculine adventures of President Teddy Roosevelt, was the perfect figure to help parents channel these hopes about the future. He believed—or at least he convinced parents—that his toys, like Erector sets, would give their boys mastery, confidence, and patience. In the mid-1920s, the top-end Erector sets sold for $25, which could be a week's wage for a parent, but Gilbert persuaded parents that these "instruments of learning" were essential for success in a time when parents were reluctant to spoil their children with too much amusement.

Erector sets were time-consuming and difficult to build, with small parts that required dexterity and came with very little in the way of written instruction. For example, an Erector Ferris Wheel usually took 18 hours to complete, and therefore, the assumption was the boy would spend more time putting it together and taking it apart than playing with it or showing it off.

Gilbert advertised Erector sets in major national magazines like "Good Housekeeping," "Saturday Evening Post," "Popular Mechanics," and "American Boy." In these ads, he often addressed the boys directly, sharing his incredible life story and asking boys to write him with their ideas for Erector-set models. Gilbert was one of the early adopters for radio as an advertising vehicle, and he also began to sell radios in the 1920s.

Sensing the United States would soon be drawn into World War II, Gilbert opened a science museum and toy store for children in New York City called the Gilbert Hall of Science on September 17, 1941. That way, mothers and their little boys on the home front would be talking about his toy lines—which by then included Erector sets, Gilbert chemistry and science kits, and the American Flyer model trains he acquired in 1938—while Gilbert's factories were conscribed to make parts for the war effort. Gilbert, however, insisted that teaching children, and specifically boys, the principles of science and engineering was his No. 1 priority, and he opened other Halls of Science in cities around the United States.

By 1954, Gilbert was the most famous toymaker in the United States, but the peak wouldn't last long. That decade, his company offered an expensive science kit called the Atomic Energy Set with a working cloud chamber, Geiger counter, and radioactive samples—which was a big failure on the market. As more families purchased televisions and more factories put out cheap toys, interest waned in big-project educational toys like Erector sets and American Flyer model railroads.

A.C. Gilbert died in 1961, leaving it to his son, Alfred Jr. The Erector set name was first sold to Gabriel Toys in the '60s, and later to Ideal Toys.

Continue readingMost Watched

ADX

Best of the Web

The Wheelmen

This elegant tribute to turn-of-the-century bicycling includes memorabilia, photographs, and an...

Club & Associations

ADX

AD

X