Are female superheroes stronger than their male counterparts? According to Mike Madrid, author of “The Supergirls: Fashion, Feminism, Fantasy and the History of the Comic Book Heroines,” they’re mentally tougher and less vengeful, but still know how to whack the bad guys. In this interview, he discusses rare ’40s superheroine titles like “Phantom Lady” and “Lady Luck,” as well as the drastic changes to Wonder Woman’s appearance and story since her debut in 1941.

When I was growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, reading comics wasn’t as popular as it had been in the ’40s or ’50s. But my older sister had comics, including a big collection of “Betty and Veronica.” Our parents encouraged us to read everything, so at 6 years old I was just one of those kids that never stopped reading comics. At a certain point my sister started throwing her comics away. I snagged what was left, and I still have them.

The first time I saw “Supergirl” I was amazed because I’d never seen a woman do the things she did. In the late ’60s, women were still represented in the media in a pretty traditional way. It seemed so fantastic to see a woman with superpowers, more fantastic even than seeing the same feats performed by men.

The men were always portrayed as one-dimensional. They had to be brave and fearless and sort of stoic. The women were given more of a range of emotions and that made them seem more fully developed as characters, and more interesting.

My friends never liked the women superheroes. In comics, the woman was usually the token and weakest member of a team. The woman would have to be saved by her male teammates or protected by them, and she wouldn’t really help as much as the men did in fighting crime.

A lot of the guys I knew when I was a kid thought that the women were useless, and that the comic-book publishers should get rid of the female characters on teams like Fantastic Four or the Justice League.

Collectors Weekly: Can you talk about the earliest female superheroes from the ’30s, the ones you call “The Debutantes?”

Madrid: Well, in the early days of comics, there were a lot of rich playboy heroes like Batman and the Sandman. They were these rich guys who would use their money to create a secret identity and go out and fight crime. Oftentimes they didn’t have a superpower, but they had some kind of interesting gadget.

Also, there were these omnibus titles—“Adventure Comics,” “Action Comics,” “Marvel Comics”—that would have maybe seven or eight different features. Batman started in “Detective Comics,” Superman started in “Action Comics.” When a character got to be popular, he graduated to his own title.

The Phantom Lady, seen here in 1949, was a debutante named Sandra Knight by day and a crime fighter by night.

Many of those omnibus comics featured one story with a woman crime fighter, a character like Phantom Lady or Miss Masque or the Red Tornado. Often, they were the female equivalent of those playboy heroes, rich young women who led lives of seemingly no responsibility. They went to a lot of parties, had a lot of nice clothes, and they always seemed bored. They usually lived at home with their parents in big mansions.

To have a little fun, these women would develop secret identities for themselves like Phantom Lady, Lady Luck, Miss Masque, and the Spider Widow. Oftentimes, they didn’t have any superpowers, but knew how to throw a punch, so they’d put on costumes and go out and fight crime.

No one suspected these women were actually daring crime fighters. It would have been as if Paris Hilton was fighting crime. Her family would never suspect it because she was usually portrayed as a ditz with no ambition or backbone. Often in these stories, once the Debutante is back in her normal clothes, her father will say, “That Phantom Lady, she sure is impressive. I wish you could be more like her,” and then the young woman will give a knowing look to the reader like, “That’s our little secret.” But her parents never suspected.

In the late 1940s, superhero comics took a nosedive. Soldiers with time to kill in their barracks had been good market for comics. After the war, as these young men re-entered the work force, comic books struggled to gain new readers. In some cases, they decided to go after women, so they gave a lot of the Debutante heroines their own titles. The stories were a blend of crime fighting with a bit of romance. They didn’t last.

One of the interesting things about the Debutantes is that they had to play down their real ambitions because they didn’t have the option to lead the kind of lives that they wanted. Their secret identities, putting on a mask, freed them, in a sense, to lead the lives they wanted and to be themselves.

Collectors Weekly: Were they feminists?

Madrid: Yes, when they were in costume, they were like the women that you saw in some of those ’40s movies. They were brainy, witty, funny, and tough. Then, when they went back to their normal, everyday identities, they were demure and acted like they weren’t all that interesting. It was as if those costumes allowed them to let their real personalities out, which was kind of a weird thing.

A psychologist claimed boys found Wonder Woman emasculating, and her lesbian undertones were a bad influence on girls.

The exception to this rule was Miss Fury, who in her everyday life was a rich, independent woman. She would put on this costume every once in a while, this black, panther costume, and be Miss Fury, but she never liked doing it. She only did it when she didn’t have any other options, and she resented having that secret identity—she thought it brought her nothing but bad luck.

Interestingly, Miss Fury was the only character of this genre written and drawn by a woman. The others were written and drawn by men. The woman’s take is probably more practical and realistic—it would be a drag to have this secret identity, it would be a burden. The way a lot of men wrote these characters, though, a secret identity was a way for these women to free themselves.

Miss Fury is the opposite of Superman and Batman. In both cases, with their secret identities of Clark Kent and Bruce Wayne, that’s not who they really are. They’re acting a certain way so that people won’t suspect they are heroes. The hero, in a sense, is who they really are. Miss Fury was the opposite. When she was Marla Drake, that’s who she was. When she had no other choice, she would be Miss Fury.

Collectors Weekly: When did Wonder Woman get her start?

Madrid: Wonder Woman first appeared in 1941, right around the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. A lot of characters in comics were already fighting the Axis powers before the United States entered the war. In Wonder Woman’s case, she was an Amazon princess, from the immortal race of female warriors from Greek mythology. The Amazons lived on an island where men could never set foot.

When an American pilot is shot down near the island, Wonder Woman volunteers to bring him back to what they call “a man’s world,” to teach that world where it’s gone astray, and to bring mankind back to the ways of peace and love that, ironically, the Amazon warriors had embraced. Wonder Woman’s mother, the Amazon queen, also makes it her daughter’s mission to fight for the rights of womankind.

A psychologist named William Marston created Wonder Woman. He wanted her to be a strong role model for young girls. He thought the male comic-book heroes of the day were mostly violent, so he wanted to create a different kind of hero who would teach girls to stand up for themselves. The message was that they could be just as strong, and contribute as much to society, as the men did.

Wonder Woman’s story included little bits of this feminist philosophy. For example, she would meet women who were being abused by men or tricked into doing things, and she would always teach them how to stand up for themselves. In that way, she was carrying an important message to girl readers.

Because she was meant to appeal to girls, Wonder Woman wasn’t drawn in as sexy a way as the other heroines of the time, like Sheena Queen of the Jungle or Phantom Lady, who wore revealing costumes. They were drawn in what’s now called “good-girl arts”—a style in which the women are very leggy and look like the pinups that were popular during the war. She wasn’t especially muscular, and she didn’t wear a really sexy costume.

But she was depicted as being incredibly strong. In those old comics, there are covers in which she’s picking up a tank or lifting up a car or an elephant. She also had the Lasso of Truth, which made men tell the truth, and she had bulletproof bracelets and the Invisible Plane.

Collectors Weekly: What happened to Wonder Woman’s powers after World War II?

Madrid: Wonder Woman’s creator, William Marston, had died by 1947. After that, a lot of the feminist, pro-female messaging that he had put into the story was dropped. More of her stories wind up focusing on her romance with her boyfriend, Steve, who was always trying to trick her into retiring or convince her that she was no longer needed so that she’d marry him. The implication was that if she married him, she’d be at home making dinner. It wasn’t like she could marry Steve and still be Wonder Woman. It was one or the other.

By 1949, the writers of Wonder Woman were turning her into a more traditional female comic-book character.

In the ’40s, Wonder Woman had a pretty strong female supporting cast composed of all these different women who were her helpers. All of that went away in the ’50s. She was still strong, but there was not that same pro-female message.

In the ’50s, she still has the Lasso of Truth, but she uses it to catch people, not to make men talk. People considered that to be her most powerful weapon, because what could be more powerful than something that would make men tell the truth? In the ’50s they robbed her of that power. The Lasso was reduced to something she’d use essentially to do tricks. It went that way into the ’60s.

In the mid-’50s, a book came out called “Seduction of the Innocent.” Its writer, a psychologist named Fredric Wertham, accused comics of contributing to juvenile delinquency. He said that the studies he did with kids showed that boys found Wonder Woman to be a terrifying figure, that she was emasculating, and that her comics had lesbian undertones that were a bad influence on young girls. So the publishers toned all of that down.

There was another strange thing in the “Wonder Woman” comics of the ’40s. Despite the fact she was strong, in pretty much every story she gets tied up. All of those bondage images were eliminated from the stories by the ’50s when things got to be more conservative.

Collectors Weekly: Was this about the same time that Bettie Page was doing those bondage photos?

Madrid: That was in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Throughout the ’40s, there was always a bondage thing in comics. Characters like Sheena and Phantom Lady, they were often shown tied up—when you look in the price guide, certain comics have higher prices because they had a bondage cover. But when the Comics Code came in 1955, all of that was removed.

In the ’40s, a lot of comics were created to appeal both to kids and men because there was a big readership of soldiers. So comics had a lot of cheesecake art and sexual situations, all of which was wiped out with the Comics Code.

One of the new rules in the Comics Code was that depictions of women had to be realistic. If you look at the comics from the ’40s, and it’s the same in movies from the ’40s, the women typically have really pointy breasts beneath tight sweaters. In “Seduction of the Innocent,” the boys looking at the comics would talk about how they were drawn to the “headlights” on the female characters. Some artists were well known for drawing these very elaborate, detailed, pointy chests, with lots of shading and shadows.

Collectors Weekly: What new roles were given to female characters?

Madrid: Well, Catwoman was a villain in the “Batman” comics, and a sort of love interest for him. At a certain point in the mid-’50s, they reformed her, I think because they thought it wasn’t good to have this beautiful woman who had this very strong sexual air about her. They moved Catwoman to the sidelines, and then they created Batwoman, who was supposed to be a new love interest for Batman.

Jimmy Olsen spoke for a lot of comic-book fans when Supergirl appeared in a 1958 edition of “Superman.”

Batwoman was well-intentioned but Batman spent so much time telling her how incompetent she was and how fighting crime was not a woman’s job that they never developed much of a romance. She was portrayed as an inferior character that couldn’t be trusted. Batman trusted Robin, a 13-year-old boy, more than this grown woman.

By the end of the ’50s, they finally created Supergirl, a female version of Superman, but she wasn’t an adult like him. She was his 15-year-old cousin. She was the surrogate daughter who would be obedient to him and his assistant and helper rather than a Superwoman who could be his equal.

By the mid- to late ’60s, Supergirl was in college, but she wasn’t a reflection of what was going on with the youth in America. She wasn’t questioning the war in Vietnam or embracing the counterculture. She was the princess from the first family in comics, so she had to represent truth, justice, and the American way.

Supergirl was always the good girl. In the same way that Wonder Woman in the ’40s was designed to show girls how to be strong, Supergirl in the late ’50s and early ’60s seemed to be a role model to show girls how to be a nice and obedient daughter.

Collectors Weekly: Who were the other female superheroes of the ’60s?

Madrid: Elasti-Girl was the female member of the Doom Patrol. A lot of the other token female members of superhero teams—like the Invisible Girl in the Fantastic Four and the Wasp in the Avengers—were always the weakest members, but Elasti-Girl was the strongest member of the Doom Patrol. She could turn into a giant, and she often wound up saving the day. She harkened back to those characters from the ’40s. She was an adult woman who had had a career, had been a gold-medal athlete, and was even a movie star. Then she became a superhero.

In 1965, the giantess Elasti-Girl, the strongest member of the Doom Patrol, stopped an attack of deadly missiles.

Characters like Invisible Girl and the Wasp were just the girlfriends of superheroes, that’s all they did. They didn’t have any other sort of personal life. They helped their boyfriends because they were hoping that eventually they’d get an engagement ring out of it.

Elasti-Girl, on the other hand, was really a member of her team, and she would often say to the men in the Doom Patrol that she was not interested in taking a backseat to them. Eventually, when this other superhero falls in love with her and wants to marry her, she puts it off for as long as possible because she doesn’t want to change her life. She doesn’t want to sacrifice her freedom just to marry some guy.

Even when they do get married, before they go on their honeymoon, she runs off with her teammates in the Doom Patrol because there’s a plane crash. She says, “I’m sorry I’ve got to go, but we’ve got to save that plane.” She was one of the first of the new generation of independent heroines, indicating where the liberated heroines of the ’70s were going to go.

Collectors Weekly: Which brings us to Batgirl?

Madrid: Yes. The Batgirl that was introduced in the late ’60s—the one on the TV show—was kind of the first of the new liberated heroines. She was a career woman. She was smart. Whereas Batwoman was always craving Batman’s validation and respect, Batgirl thought she was in a lot of ways just as qualified to fight crime as he was. She didn’t need Batman’s approval all the time. As a result, he wound up respecting her more and treating her as more of an equal than he did with Batwoman.

No one suspected these women could be so daring. It would have been as if Paris Hilton was fighting crime.

The other difference between the two characters is that Batgirl debuted a little over 10 years after Batwoman. By that time, comics couldn’t be written the way they had been in the ’50s. Batman really couldn’t malign Batgirl in the same way as he had Batwoman because the world had changed so much.

Meanwhile, also in the 1970s, the writers of “Superman” comics introduced Power Girl. She was a cousin of Superman from an alternate Earth, kind of a feminist version of Supergirl. She was tough, strong, and thought she was just as capable as any man. She refused to be pushed around by men, especially the men that she worked with in the Justice Society.

Power Girl is typical of how some of these feminist characters were written—militant, strident, and angry—which is perhaps the way many of those male writers saw women’s liberation. Reading the stories now, they do seem a little heavy-handed, but at the time, the content was very topical in terms of women’s liberation.

Collectors Weekly: Were there characters in the ’70s who were both liberated and sexy?

Madrid: Sure. Black Widow was this rich jetsetter who could afford to be a crime fighter—it gave her a thrill. She didn’t do it because she was someone’s girlfriend. She did it because it gave her a life the sense of adventure that she craved. She was very confident, had relationships with men, and was very sophisticated.

Black Widow represented the women’s-liberation movement, but also the sexual revolution, in the sense that she had a number of somewhat-casual sexual relationships with men. It wasn’t done in an overt way, but Black Widow was definitely in control of her own life and was not looking for a lot of approval.

Vampirella was another one who straddled both movements. She first appeared in 1969, and she wore this very skimpy costume that was just these two strategically placed straps. When I was a kid, I remember that it felt like you were buying a men’s magazine when you bought Vampirella comics because she hardly had anything on. Vampirella wasn’t actually all that racy of a character in terms of her nature, but certainly was in terms of the way she was drawn. She was the first shot fired in the sexual revolution of comics.

In the ’70s, some of the rules of the Comics Code loosened up, as more female characters were drawn wearing very revealing costumes. To some degree, it was a return to the way things had been in the 1940s. In the decades between, in the ’50s and ’60s, the costumes were more conservative and covered everything up.

Another aspect of the 1970s is you start to see comics written for an older reader, or to appeal to both younger and older readers. There were more sexual situations being hinted at in a subtle enough way that older readers would understand it, but younger readers would just go right by it.

Collectors Weekly: What was the significance of Storm?

Madrid: She first appeared in ’75, and she was the first major black heroine. She was independent and strong, but she wasn’t written in a heavy-handed way. It was just who she was. She was very regal and stood up for herself, but she wasn’t really high-handed about it and didn’t get into feminist preaching the way some of the other female characters did. In the ’70s, she was one of the first strong, fully realized characters.

Collectors Weekly: Why did Ms. Marvel fizzle out?

Madrid: In the ’70s, Marvel Comics wanted to create a strong female character because they didn’t have a woman who headlined her own title the way DC had with Wonder Woman. They were trying to create their own iconic, liberated, strong heroine. Rather than create someone from scratch, they made Ms. Marvel, the female version of Captain Marvel, even though she wasn’t his partner. She had the same powers and even wore a variation of his costume.

There were a lot of good intentions, but she never became popular with the readers. She’s been around ever since then, but her title only lasted about two years, which is generally the case with comics that star a woman. Most of them have a hard time gaining enough of a readership to last. Some will last five or six years; some will last three issues.

When you look at the history of comics, they’ll try a lot of these new characters but usually they don’t gain the right number of readers. Wonder Woman is the only superheroine who’s been around, with few interruptions, since 1941. Every other female superhero had little runs with their own titles, but eventually they got canceled.

Collectors Weekly: How did Wonder Woman change in the ’70s and ’80s?

Madrid: In the late ’60s they were trying to make her more popular and more relevant, so they took away her powers and made her into a female James Bond in a white pantsuit. Then, in 1973 during the women’s-liberation era, they gave her back her powers because people like Gloria Steinem were heralding Wonder Woman as an early feminist icon. They also put her back in her costume. The TV show in the 1970s really renewed her popularity.

By the ’80s, though, she was waning in popularity again, so in ’87 or ’88, they had this big cosmic event in which she was wiped out—it was as though she never existed. Later she was reintroduced and her story was updated. We were supposed to forget 45 years of stories. In the new stories, Superman, Batman, and everyone met her for the first time. She was stronger, and her story made more sense because it went back to the roots of the character.

Recently they did it again. It was a big deal in the news, especially the tension around how they had changed her costume and put her in pants. What I noticed more than the pants was that they changed her story as well, including her origin. It remains to be seen what that’s going to be like, but they’ve started her back at the beginning so that everything you knew about her is no longer the case.

They’ve actually done this thing with Wonder Woman seven or eight times in the 69 years she’s been around. They don’t do that sort of thing as much with Superman and Batman. They may tinker with their stories a little bit, but they generally don’t wipe the slate clean and start all over.

Collectors Weekly: With Spider-Man, though, they erased his marriage?

Madrid: Yes, that’s true. In “One More Day,” Spider-Man and his wife made a deal with the devil. They could save his aunt, but the price would be wiping out their relationship. So they accepted it and it was as if everything was back to the ’80s, before they got married, as if it had never happened. He’s still single and they’re not together. A lot of people were really mad about that.

A lot of women are drawn to the idea of these women as protectors, rather than as an avenger or scourge on evil.

Of course, they also “killed” Superman in the ’90s. That was kind of the beginning of the big ’90s collecting bubble because people who didn’t collect comics heard that there was going to be this super valuable “Death of Superman” comic that was going to come out. Everyone bought it up. Then the people who ran comics companies said, “Well, if we keep creating these big, hyped-up events, people will buy up more of our comics.” And people were buying, supposedly because they thought it was going to be an investment, but it turned out to be a bust.

So yes, they killed off Superman. He was gone for maybe about a year, and then he came back with a mullet. They were trying to make him more edgy, so he had this really bad hairdo, almost like Richard Marx.

In the ’90s they did a lot of that, trying to make these characters more edgy. They changed Wonder Woman’s costume. She had something of a bondage costume with these biker shorts, and she looked tougher. They orchestrated a lot of hyped-up events that were designed to drive the collectors’ market. Ultimately, these gambits just wound up producing a lot of really bad comics.

Collectors Weekly: What happened to female superheroes in the 1990s?

Madrid: The ’90s is when what I call “stripper culture” became popular, thanks to the Internet, which made pornography more mainstream. There wasn’t such a stigma about going to strip clubs. Even the way porn stars and strippers looked became more popular, as plastic surgery became more easily accessible.

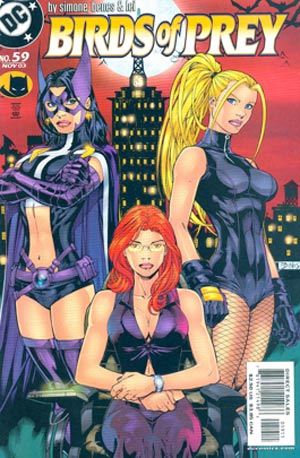

A trio of highly sexualized heroes—Huntress, Oracle, and Black Canary—share the cover of “Birds of Prey,” #59, in 2003.

As a result, a lot of the women in the comics wound up looking like that, with really big breasts and big lips and big hair and really long legs. It was also the era when supermodels were really popular, and you have this idea that you could be a big celebrity just based on your appearance. You didn’t have to actually have any real talent or brains.

The ’90s was also a time where you had a lot of new, independent publishers like Image and Valiant springing up. They were trying to do different things and grab a share of the buyers’ market. Often what they did was have these very sexualized women headlining these comics, characters like Lady Death and Ghost.

They had that stripper look about them, they were very strong, and in many cases they were very, very violent. It was the first time in 50 years that numerous female characters were headlining comics. If you looked at the shelves of comics at that time, there was a lot of skin, and you wouldn’t have necessarily thought that these were strong, pro-female role models.

This was the era when sexualized violence went mainstream. In a lot of the imagery, these heroines almost look like they were being humiliated. Some of the images had a voyeuristic quality about them, like a cover with just some heroine’s face with someone’s hands around her throat, or just a heroine’s face being held under the water, depicting her being drowned.

Even though bondage images were common in the ’40s, in the ’90s there was a different edge to it. In comics, especially on covers, there’s almost always going to be an image of the hero or heroine in a dangerous situation because it drives sales. But there’s not often a cover image of Superman looking kind of sexy but beaten up and bloody at the same time. There is something obviously disturbing about images of women, even of comic-book characters, looking kind of sexy but battered at the same time.

Collectors Weekly: What was the role of alternative comics at that time?

Madrid: Women created a lot of the alternative comics of the ’90s. In many respects, they were more interested in telling some sort of personal story rather than writing about a crime fighter. They were drawn to independent or alternative comics in the first place so they could do things that didn’t fit in with mainstream comics publishing. The result was a more diverse representation of women in those comics.

Collectors Weekly: How do characters like Promethea or the women in “Birds of Prey” fit into this?

Madrid: Promethea is an alternative version of Wonder Woman. She is literally a figment of someone’s imagination and she takes the form of different women. It’s very mystical stuff, and it’s written as a journey of discovery for this girl named Sophie, who is the latest incarnation of Promethea. She’s learning a lot about herself, and she’s learning about who Promethea is and what her powers are when she is Promethea.

“Birds of Prey” was the first female buddy comic. Before, there weren’t a lot of friendships with women shown in comics. In “Birds of Prey,” you had these two characters, Black Canary and Oracle, who used to be Batgirl, teaming up to fight crime. At first, it’s a boss-employee relationship, but over time, they learn more and more about each other, even though they never actually meet. They wind up becoming long-distance friends who learn to help each other overcome traumatic events in their pasts.

As a team, Black Canary and Oracle took on cases that other superheroes might have ignored, which showed a particularly female approach to doing good. A character named Manhunter, who first appeared in the early 2000s, was the same way. She took a personal approach to fighting crime, very ruthless, but did a lot of things that Superman and Batman wouldn’t. For example, there are stories of all those women who disappear in Tijuana: at one point, Manhunter goes down to Mexico to investigate and rescue all these women who have been held captive.

This was a uniquely female approach to fighting crime. Writers acknowledged that a woman was not necessarily going to handle a job the same way a man would. Women wouldn’t necessarily think the same things are a threat. Or, they might approach a situation in a more helpful way, rather than just beating somebody up.

A lot of women whom I’ve talked to, who have read my book, are very drawn to the approach of these kinds of heroes, and they’re not put off by the sexual imagery. They are more interested in the way the women are written. There’s one word that keeps coming up in terms of what seems to appeal to them and that’s “protector.” In letters or emails that I’ve received, they always say that they were drawn to the idea of these women who are protectors, rather than as an avenger or a scourge on evil.

The men are always represented as people who are going to smash crime in the face. It’s an interesting twist, that there’s an effort being made now to try to write women in comics as protectors. You see them expanding on the whole idea of what it means to do good.

Supergirl was the princess of the first family in comics, so she had to represent truth, justice, and the American way.

In the current series of “Power Girl,” in her everyday life she runs a company working on environmental issues, and she realizes that every problem can’t be solved by punching it in the face. She also gets a bunch of other heroines together to take relief supplies to a country that had been devastated by an earthquake. It’s a more proactive role in trying to help the world rather than just reacting to someone trying to take it over. They’re using their powers to make the world a better place. That’s a unique female twist on the idea of the superhero.

In the last 10 years or so, we’ve seen these characters, who may not be mothers, wind up taking on a maternal role in terms of their relationship with the world. Jenny Sparks, who led this team called the Authority, was a tough, hard-drinking, smoking, foul-mouthed character, but she had this very maternal view of the world. Even though she had this really grizzled exterior, she would say the world was under her protection, and that it was her responsibility. That’s a direction that superheroines are going in now, rather than being an accessory to a man.

Collectors Weekly: For collectors, are the female superhero comics of the 1940s hard to come by?

Madrid: They’re hard to acquire unless you are willing to spend a lot of money. When a lot of the female characters had their own titles, they weren’t as popular as Superman or Batman so there were not as many copies printed. Additionally, I don’t know if girls kept their comics in the same way that boys did. So for early Wonder Woman and other comics, it’s probably a combination of low initial print runs and not being saved as much. That might make them more rare.

In 1949, Superman time-travels into the future, where he meets a superheroine who looks a lot like Lois Lane.

In the late ’40s, a lot of the Debutante heroines had their own titles, so characters like “Venus” and “Blonde Phantom” and “Lady Luck” had a few issues. They’re definitely around. You see them at conventions every once in a while. They’re usually pretty pricey because they don’t come up that often.

The omnibus comics from the ’40s featuring female superheroes had bigger print runs. They had better sales potential because there’d be several different characters, and kids in those days probably thought, “I’m getting a lot more for my dime.” A copy of something like “Action Comics” or “Flash Comics” or “Adventure Comics” is easier to find today. Then it becomes a question of if you’re collecting for condition or if you’re just reading them for the stories. They’re harder to find in good condition, but you’re more likely to find a Phantom Lady or Lady Luck story in an omnibus comic.

Phantom Lady ran in a series called “Police Comics.” Later, in the ’40s, she graduated to her own title. Miss Fury was first published in the newspaper, after which they collected her panels into a comic book. There was a title called “Smash Comics” that had Lady Luck stories. If someone’s interested in a particular character, they just need to do their homework to find out which series their stories appeared in. It’s pretty easy to find.

The Internet is great, but you’re more likely to find older comics at conventions. A lot of comic-book stores don’t even deal with back issues anymore. It’s really gotten to be more of a thing where various dealers just cater to serious collectors, at conventions and on the Internet.

Collectors Weekly: Has the collectability of these comics put them out of reach of those who just want to read the stories?

Madrid: Not necessarily. It really seems to only be the case for comics from the ’40s and the ’50s. If you go to a thrift store or flea market, you can look through a box where everything is a dollar or 50 cents, and sometime you can find a copy of “Ms. Marvel No. 1.” They weren’t necessarily printed in large numbers, but the demand doesn’t seem to be there. Some of these titles have been reprinted in the last 20 or 30 years, so it’s not necessarily that hard to find in some form or another. They are not all rare.

One of the things that I’ve heard from a lot of the younger women who have read my book is that they are interested in the characters from the ’40s and ’50s. If there is a surge of interest in these comics, maybe publishers will start reprinting some of the old stories. They’re great tales, and I think there is definitely a market out there with younger women who would like to read them.

(All images in this article courtesy Mike Madrid)

When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men

When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men

Women Who Conquered the Comics World

Women Who Conquered the Comics World When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men

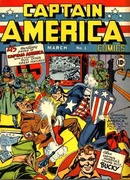

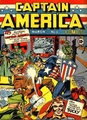

When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men Golden Age Comics: When Captain America Punched the Lights Out of Hitler

Golden Age Comics: When Captain America Punched the Lights Out of Hitler Wonder Woman ComicsBefore the United States entered World War II, our male superheroes like Su…

Wonder Woman ComicsBefore the United States entered World War II, our male superheroes like Su… Underground and Alternative ComicsIf 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos o…

Underground and Alternative ComicsIf 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos o… Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat…

Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

love the images! great stuff.

Thanks, Dean!

Along the same lines, I just found out about this movie, “The History of the Universe, As Told by Wonder Woman.”

http://vaquerafilms.com/wonderwoman/

Wow!!!Super article by a “super” writer.

Good overview – let me add an anecdote on the ’80s, which get skimmed over.

The most popular title of the era, X-Men, wasn’t just a vehicle for Storm – it was a home for unappreciated female characters like Ms. Marvel, Dazzler, Tigra, She-Hulk, Misty Knight, etc. to guest star. This didn’t come off as weird because the team’s heavy hitters were already women, following writer Claremont’s mantra of “Is there any reason this character can’t be a woman?” Meanwhile it is the male lead, Cyclops, who is forced into a binary choice between marriage and heroism. A nice inversion of the standard superhero formula that is more well-known than a survey would suggest.

Very well done! Love the story’s still love them today of many super chicks.Thank you for your insight and time to write this.Keep Read’m and collect’m.Frosty21

Seems strange to not mention Mary Marvel at all. She beat Supergirl and Ms Marvel to the punch of a publisher attempting to create a female version of their male hero that was more than just a sidekick.

Should be noted that while Wonder Woman was the biggest success of the female superheroes introduced in the comics, she wasn’t the first. There were at least nine that pre-dated her and not all wore skimpy outfits (Woman in Red, Miss Victory).

There was a comic book (one of a kind, like a paperback book) that had a character (or maybe the title of the book) called S*P*RM*N (the asterisks were part of the word). It was a parody of lots of current themes and was, I think, written by some contributors to MAD Magazine – it had that “look,” if I remember correctly. I’m thinking mid-60s… Any ideas?

If any female superhero owned the ’80s, it was X-woman Jean Grey/Phoenix, whose journey from Marvel Girl to Phoenix/Dark Phoenix was not only central to the most popular book of the decade – and later played out in three different animated TV series and three box office smashes – it’s been recycled so many times that it’s become a cliche. Scarlet Witch anyone? Green Lantern? Even Invisible Girl became a “Woman” followed a Dark Phoenix-y episode where she was mind controlled and her full potential was unlocked.

Black Canary seems awesome, would love to see her developed with this visual and not huge breasts and no underwear, the modern version.